Pride, Pancakes and Progress

Keith TESTA

Alliance, the primary LGBTQIA+ group on campus. The Aulbani J. Beauregard Center for Equity, Justice and Freedom. The Diversity Support Coalition. Safe Zones, an educational program to raise awareness of LGBTQIA+ issues. TransUNH.

For a select few in the standing-room- only crowd, that list resonated as a lot more than a bulleted account of Barre’s credentials.

It represented once-unimaginable progress. Progress they all left the first fearless fingerprints on.

Those individuals will be forever unified as trailblazers in the pursuit of LGBTQIA+ rights at UNH and beyond.

Whether it was taking on the state’s governor and the university itself to fight for the founding of the Gay Students Organization (GSO) more than 50 years ago, or creating the pancake breakfast as an annual opportunity to celebrate success and applaud allies, their sweat and tears broke barriers that forever changed things at UNH, creating an atmosphere in which the many organizations Barre has participated in could not only exist but thrive.

This year’s 30th Pride and Pancakes celebration and the 50th anniversary of the GSO’s founding provided the perfect backdrop for these critically influential figures to mark significant milestones while envisioning those Barre’s generation might one day celebrate as well.

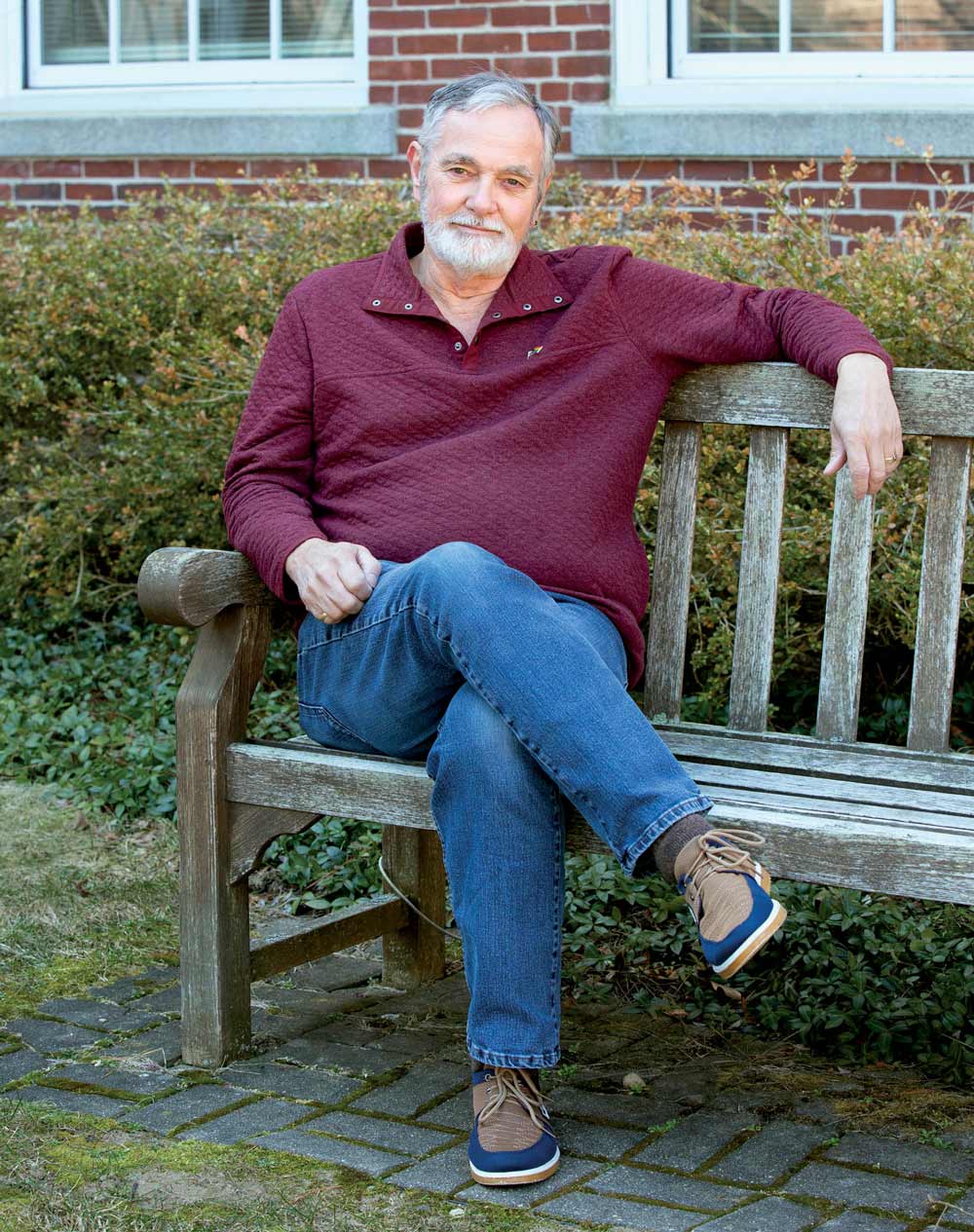

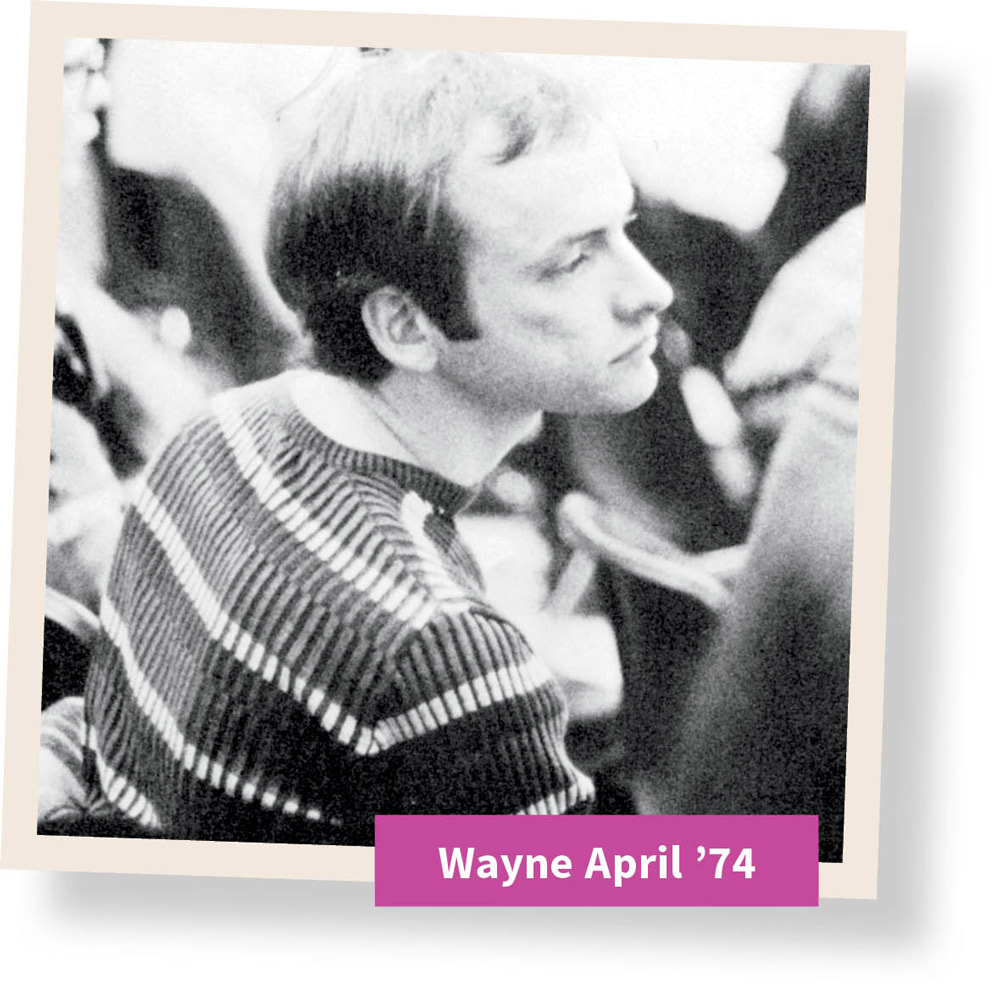

WAYNE APRIL ’74

Taking time to find himself: I was at UNH for two years but I got really depressed — I think it was the combination of being gay and not being out and not knowing what I wanted to do career-wise — so I left school for a year and went back to work and got my head together. Then I reapplied and went back, and that’s when everything changed.

Coming out: There were a lot of letters to the editor of the student newspaper back then from gay students, but they were always anonymous. I had a small group of friends who talked about the letters, and we said maybe someone should go talk to the newspaper. We hadn’t really organized ourselves into the GSO then, but we met as a group and agreed I would meet with the newspaper editor, and that’s kind of where it all started.

On taking the lead: I was the only one willing to do it. Most of the other students still didn’t want their names out there — things aren’t perfect now, but they were significantly less perfect then as far as having your name be out there as a known gay person. So for the most part, I was the point person because mine was the name that was out there.

LARRY MEACHAM ’76

First foray into student politics: I was living in Randall Hall and a student senator on my floor had to leave for a few days due to a family matter, and I stepped in for him during one meeting where Paul Tosi was discussing funding for the GSO in front of the caucus. That was my first real entrance into the student political world, standing in for that one vote. And I did vote in favor of the funding.

Being president after the GSO battle: Thanks to the work Paul Tosi and Wayne April did, I was able at that point to basically be part of a community where the state would leave the university students alone — all the students, not just the gay students — and let us live our lives as students are supposed to.

Meeting with Thomson: When I was student body president, the primary emphasis was just let students be students. Having Thomson meet with students was a good opportunity for me to represent the student body, and I don’t remember it as being contentious. I think it was a testament to student government’s ability to both represent and watch out for the student body at the same time.

CARI MOORHEAD ’99 Ph.D.

Coming out in a war zone: I came out between high school and college, but I was moving from Dublin to Belfast at the time, and The Troubles were raging. I was there at some of the hottest and heaviest times of fighting. So I was trying to figure out how to read things when you’re in a war zone — I was looking for who my people are and at the same time looking to try not to get killed.

Arrival at UNH: I was a graduate student at Northeastern and in 1988 I got pulled for a green card in the lottery, but it took almost a year-and-a-half to process. I applied for an academic advisor job in the business school at UNH, but then had to go back to Ireland to complete the process. I landed back in Boston on a Saturday with my green card and had my interview at the business school Monday morning. I still had jet lag.

Origins of the Pancake Breakfast: I was on a Herstory panel for Women’s History Month and that’s when I first heard the story about the Gay Student Organization and the pancake breakfast controversy with the governor. By the time it came to me to speak, I just said to the group, “We should throw a pancake breakfast for ourselves, how hard could that be?”

PAUL TOSI ’74

How it all started: I took office as student body president in February 1973, and it was some time in April when the GSO approached us. They had filed all the necessary paperwork, so we approved them as a recognized student organization. The administration took the recommendation of the student organization committee, but then all hell broke loose because the governor found out and the Union Leader found out.

The right thing to do: From the time I was very young, I loved politics. I had marched for civil rights as a child, and to me this was no different, this was just a group fighting for their civil rights, for human rights. So it was simply the right thing to do.

Inspiration to talk to the board of trustees: The night before I gave that speech to the trustees, my father called me. He worked for the Portsmouth Herald, and the editor showed him an editorial about what I was about to do. He asked me why I was doing it, and I told him it was just about human rights. He said, “I just want you to know you have the full support of your mother and I.” That gave me incredible courage.

Living History of the LGBTQIA+ Legacy

With the help of Archivist Elizabeth Slomba and Public Services Coordinator Morgan Wilson, students were able to sift through dozens of documents and primary sources of the fight to establish a Gay Students Organization on campus.

“It was a great experience for us to be able to do this academic research at the UNH Library where the staff was so open, so happy that we were there, and so eager to celebrate the work we were doing,” says professor Holly Cashman, who is also chair of the Languages, Literatures and Cultures Department and a professor in women’s and gender studies.

At this year’s Pride and Pancakes Breakfast, Cashman and students were on hand to celebrate the milestone and the history that many of them had just recently learned about. Anna Rhoda ’25, undergraduate teaching practicum assistant for the class, told the audience that the 26 students in Cashman’s course had spent the semester scouring primary sources from the 1970s on the creation of the Gay Students Organization, the controversy and media coverage, the reaction from the governor and the subsequent lawsuit that resulted in the affirmation of the rights of students to form an organization, and the history of the pancake breakfast.

DIG IN: THE HISTORY OF A MOVEMENT

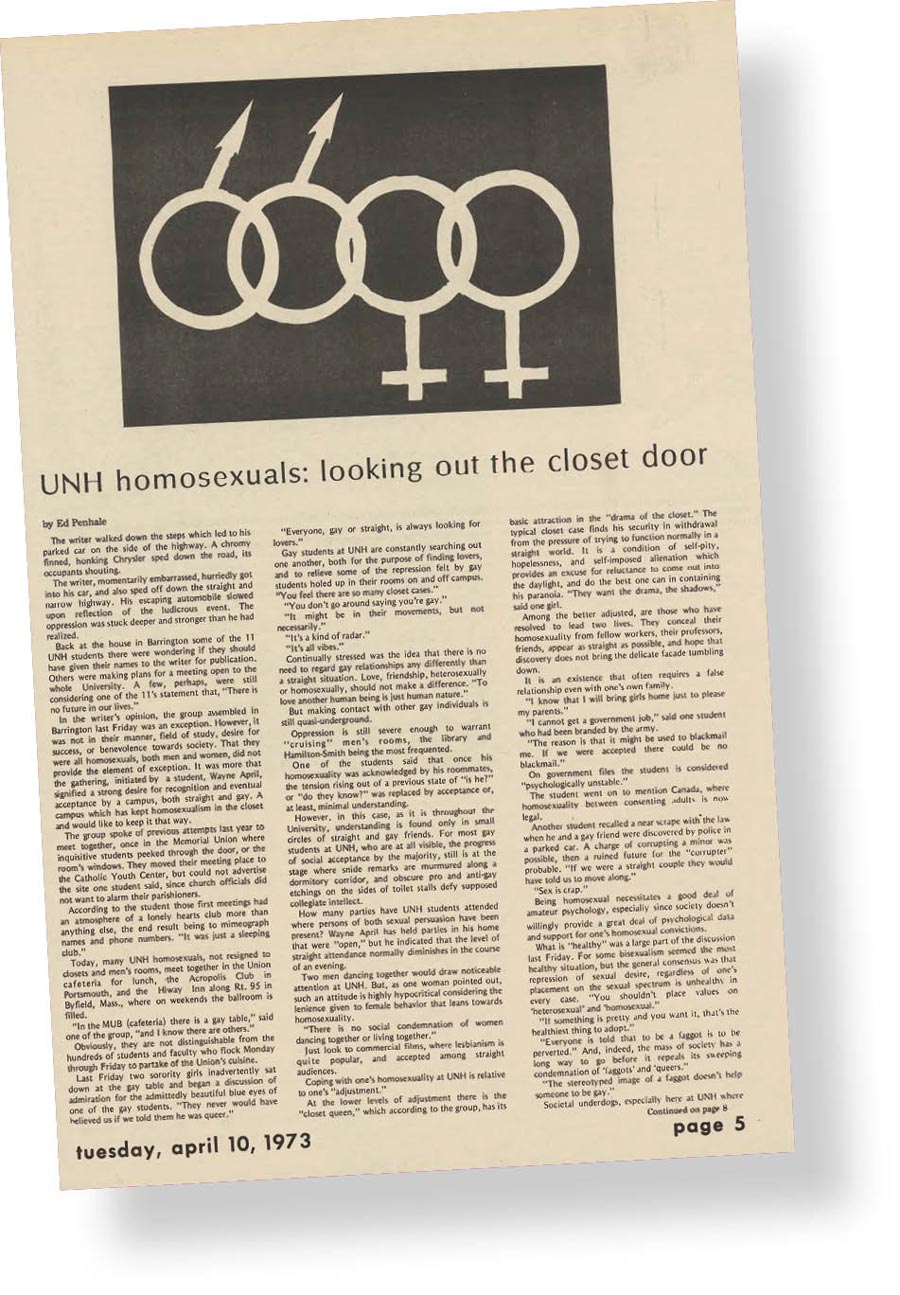

It was the spring of 1973, and the interview would in many ways ignite a groundbreaking controversy — on campus and in courtrooms.

But before he could have predicted all that, April was just a nervous student who made the decision to follow through with his interview. TNH published the article on April 10. “And then the rest is history,” April says.

Well-documented history. April would eventually stand before the UNH board of trustees, give testimony in front of the U.S. Court of Appeals and be interviewed by prominent Boston news personality Mike Barnicle as he quickly became the face of UNH’s Gay Students Organization (GSO) and its ultimately victorious battle to be recognized as a student organization. A few key highlights from that time:

May 1973

November 1973

Jan. 16, 1974

May 1974

That wasn’t the end to students’ tangling with Thomson. He unwittingly played a role in the creation of an annual Pride and Pancakes celebration of the LGBTQIA+ community that commemorated its 30th anniversary this past spring.

Dec. 30, 1974

1993

WAYNE APRIL ’74

Taking time to find himself: I was at UNH for two years but I got really depressed — I think it was the combination of being gay and not being out and not knowing what I wanted to do career-wise — so I left school for a year and went back to work and got my head together. Then I reapplied and went back, and that’s when everything changed.

Coming out: There were a lot of letters to the editor of the student newspaper back then from gay students, but they were always anonymous. I had a small group of friends who talked about the letters, and we said maybe someone should go talk to the newspaper. We hadn’t really organized ourselves into the GSO then, but we met as a group and agreed I would meet with the newspaper editor, and that’s kind of where it all started.

On taking the lead: I was the only one willing to do it. Most of the other students still didn’t want their names out there — things aren’t perfect now, but they were significantly less perfect then as far as having your name be out there as a known gay person. So for the most part, I was the point person because mine was the name that was out there.

Receiving support: It seemed like the more the controversy erupted, the more support we got. And not just from within, but from outside the university — we got letters of support from all over the country. And then the ACLU took on the case. If it hadn’t been for them, I don’t know what we would have done because we didn’t have the money to hire an attorney.

Recognizing the gravity of what happened: We were aware of what we were doing, but we had no idea the court case was going to become the precedent that it did. It really was a head-spinning time because we were approached by a lot of people who wanted us to do speaking engagements or interviews. We knew we were doing something significant, but it wasn’t until the dust settled that we realized, wow, we really accomplished a lot.

Not holding anything against UNH: I had no reason to hate the university. They were as much a victim in some ways as we were — it was a few individuals causing a problem, and individuals in positions of power who were abusing it, primarily the governor and the publisher of the state’s biggest newspaper. But I never got any negative feedback from anyone that actually worked at the university, and some people — like Bill Kidder and several others — bent over backwards to help us.

Advice for current LGBTQIA+ students: When it comes to what’s right, listen to your heart, not your head. Fifty years ago, my heart told me there was nothing wrong with me and it was the world that needed to change. My head, and many people, told me I was putting myself in personal danger from bigots as well as jeopardizing my relations with family and friends and torpedoing any chance of a meaningful career if I came out. But I went with my heart, because the status quo made me miserable.

Be yourself: You just have to live as normal and as openly as you can. Really the most transformative thing for the general public is just to know gay people. I always made a point to be out at work, but let it be organic — people would talk about their weekend, and I would say, “My partner and I went to so and so.” Just be honest with yourself and be organically, naturally honest with other people.

On the current LGBTQIA+ climate on campus: I think it’s great. I’m proud of the fact that these students feel comfortable being themselves — even today, it’s not always a comfortable thing to be out. Between that and the transgender movement, it takes a lot of courage to put yourself out there and say, “This is who I am.” I’m proud of the fact they can do that now.

Supporting future students: I’m hoping I can leave a little bit of money for the LGBTQ+ students. I think when students come to campus, they are so overwhelmed with all the responsibilities of just being a student that in the midst of all that they’re not working on themselves. There really needs to be a lot of mental health support for students. I’d like to be able to leave something to UNH to help students get the resources they need.

LARRY MEACHAM ’76

First foray into student politics: I was living in Randall Hall and a student senator on my floor had to leave for a few days due to a family matter, and I stepped in for him during one meeting where Paul Tosi was discussing funding for the GSO in front of the caucus. That was my first real entrance into the student political world, standing in for that one vote. And I did vote in favor of the funding.

Being president after the GSO battle: Thanks to the work Paul Tosi and Wayne April did, I was able at that point to basically be part of a community where the state would leave the university students alone — all the students, not just the gay students — and let us live our lives as students are supposed to.

Meeting with Thomson: When I was student body president, the primary emphasis was just let students be students. Having Thomson meet with students was a good opportunity for me to represent the student body, and I don’t remember it as being contentious. I think it was a testament to student government’s ability to both represent and watch out for the student body at the same time.

Coming out: I didn’t come out until I moved to San Francisco in 1978. But I’m really proud of what UNH has done over the years since I attended; they’ve created such an inclusive community. The students at this year’s pancake breakfast felt comfortable being who they are, and that in and of itself is a great thing.

Leaving his mark – literally: Last year I was in New Hampshire in June after my 50th high school reunion. I hadn’t stepped on campus since 1978 before I left for San Francisco. I wanted to go to my old dorm – senior year I had a single, and the moulding was falling off near the closet floor. I had etched my initials and probably a date in there, and I was curious to see if it was still there. Turns out they had corrected the molding, and I decided it was probably better not to rip it off.

Looking ahead: What I would really like to do is set up a board of alumni that may be interested in seeing how we can lend our support to LGBTQ+ students. It could be for undergraduate or graduate students, whether it’s mentoring we set up or maybe there are alumni interested in setting up scholarships. I think we would go into this with a very open mind and an aim to partner with and assist those who are most in need.

On making the new venture a success: I don’t think we can be successful unless we hear from students. And whatever we come up with has to be reflective of the environment as it changes and must meet the student body and their needs. What we have to put in place is something that will always be there, that will always be helpful, regardless of politics. Students are there to learn, they’re there to grow, to appreciate friendships and family, and that should never be taken away.

Advice for next generation of activists: I would say be respectful and proud of who you are and let others understand and accept you for who you are. It wasn’t easy back then, there were still a lot of people who didn’t like us. But love is love no matter who you are. I would say move forward and enjoy life, but don’t enjoy life such that you ever infringe upon anyone else’s.

CARI MOORHEAD ’99 Ph.D.

Coming out in a war zone: I came out between high school and college, but I was moving from Dublin to Belfast at the time, and The Troubles were raging. I was there at some of the hottest and heaviest times of fighting. So I was trying to figure out how to read things when you’re in a war zone — I was looking for who my people are and at the same time looking to try not to get killed.

Arrival at UNH: I was a graduate student at Northeastern and in 1988 I got pulled for a green card in the lottery, but it took almost a year-and-a-half to process. I applied for an academic advisor job in the business school at UNH, but then had to go back to Ireland to complete the process. I landed back in Boston on a Saturday with my green card and had my interview at the business school Monday morning. I still had jet lag.

Origins of the Pancake Breakfast: I was on a Herstory panel for Women’s History Month and that’s when I first heard the story about the Gay Student Organization and the pancake breakfast controversy with the governor. By the time it came to me to speak, I just said to the group, “We should throw a pancake breakfast for ourselves, how hard could that be?”

What the breakfast is about: [When we first started the breakfast], a colleague knew someone with a griddle. When I met this guy, he looked to me like a stereotype of someone I might be afraid would not be a fan of my lifestyle. The moral of that story is I always feel like I have to be very careful to check my own biases. … It’s about where are those opportunities for people to share that they are allies, and that’s what’s at the heart of the pancake breakfast.

Impact of the breakfast on the community: I hope the pancake breakfast is an example that reminds all the people around us that this is not a done deal, and they will then be encouraging of us living our best life. Because when you see your colleagues around you supporting you to live your best life, you will feel less at risk. So this cultural manifestation of support has a ripple effect that is really, really important.

Being open with incoming and prospective students: I don’t start off by saying, buckle in, this is the LGBTQ+ friendly section of the program — but I might mention that my wife and I are both alums and our daughter goes to UNH. So I’m not throwing up a rainbow flag, but it’s the subtle normalization of being honest about who I am. I’m putting it out there that UNH is a place where we come from a lot of places, we have a lot of world views, and we want to welcome people to be themselves.

Creating an inclusive atmosphere: I had a meeting recently with an international student who was sharing that they feel the community that we want them to feel, because we do a lot of things to signal to people that they are welcome, and we want them to be their full and whole selves and we also want them not to impinge on other people’s ability to be their full and whole selves. We want to keep signaling that in all senses of it.

On the Lifetime Achievement Award and UNH’s LGTBQ+ legacy: At the end of the day, I’m very proud that we’ve been able to bring to light that UNH put a stake in the ground in early days. That award isn’t for me, it’s for all of us — this is a huge hug to all of the people who have been part of us making change over time. I think it does give people hope in the broadest sense that you get to be you here.

Still fighting: I think there’s a worry now where we have replaced some of the concerns, we faced with those around trans inclusivity — it’s the same rhetoric we used to hear about other members of our community. So on the one hand we’ve come a long way, but on the other hand some of that concern is still unfortunately alive and well. While I’m so grateful to be celebrating 50 years of progress and 30 years of celebrating progress, it’s a cautionary tale that we can’t be complacent.

What lies ahead: I think whatever happens moving forward, it is helpful to remember that you didn’t get here on your own — you are standing on the shoulders of those who came before you, and you, too, will be the shoulders upon which other people stand. And that gives me great joy and hope.

PAUL TOSI ’74

How it all started: I took office as student body president in February 1973, and it was some time in April when the GSO approached us. They had filed all the necessary paperwork, so we approved them as a recognized student organization. The administration took the recommendation of the student organization committee, but then all hell broke loose because the governor found out and the Union Leader found out.

The right thing to do: From the time I was very young, I loved politics. I had marched for civil rights as a child, and to me this was no different, this was just a group fighting for their civil rights, for human rights. So it was simply the right thing to do.

Inspiration to talk to the board of trustees: The night before I gave that speech to the trustees, my father called me. He worked for the Portsmouth Herald, and the editor showed him an editorial about what I was about to do. He asked me why I was doing it, and I told him it was just about human rights. He said, “I just want you to know you have the full support of your mother and I.” That gave me incredible courage.

An ally on the board: I had a great audience in the board of trustees. Mildred McAfee Horton was 73 or 74 at the time – she had previously become the highest-ranking woman in the military in the U.S. and fought for and achieved equal pay for women in the military. She just had an incredible basis of understanding of humanity. Her approach was simple – these were children of New Hampshire citizens, and they were just asking for equal treatment to any other group.

Bigger than UNH: That case made a difference not only for a generation of students at UNH and campuses throughout the country but also the entire LGBTQ+ movement. That federal case in district court, Judge Bownes’ decision has been cited for over 50 years in gay rights cases across the country.

On reuniting with Wayne at the pancake breakfast: I look at Wayne and I see a mature man, but he was basically no different 40 years ago — he approached everything sensibly, he presented his case, he was steady and controlled and he had a mission, which quite simply was acceptability. To just get together with him, he had the exact same look on his face, the exact same reaction, that calm approach to things. I learned a lot from that, that I could incorporate it into all aspects of my life and be happy.

Strength in numbers: You just have to stand out and stand up for what you are and what you believe in. I think its critically important for people who want to fight for LGTBQ+ rights now that they join forces with other groups. Because it isn’t just us – it’s voting rights, it’s minority groups. People are trying to marginalize so many different groups. We can’t limit ourselves to just our battle.

Why the fight is important: The difference in the State of New Hampshire now compared to 1973 is phenomenal, and that movement at UNH played a role in that. I’m so proud of the university because they took that seed and expanded it. This is still an important story to tell, so people realize that it’s only been 50 years, it’s just one step back in time and look where we are now and how easy it would be for us to slide back if we don’t keep advocating.

Living History of the LGBTQIA+ Legacy

With the help of Archivist Elizabeth Slomba and Public Services Coordinator Morgan Wilson, students were able to sift through dozens of documents and primary sources of the fight to establish a Gay Students Organization on campus.

“It was a great experience for us to be able to do this academic research at the UNH Library where the staff was so open, so happy that we were there, and so eager to celebrate the work we were doing,” says professor Holly Cashman, who is also chair of the Languages, Literatures and Cultures Department and a professor in women’s and gender studies.

At this year’s Pride and Pancakes Breakfast, Cashman and students were on hand to celebrate the milestone and the history that many of them had just recently learned about. Anna Rhoda ’25, undergraduate teaching practicum assistant for the class, told the audience that the 26 students in Cashman’s course had spent the semester scouring primary sources from the 1970s on the creation of the Gay Students Organization, the controversy and media coverage, the reaction from the governor and the subsequent lawsuit that resulted in the affirmation of the rights of students to form an organization, and the history of the pancake breakfast.

Students also presented at the Live Free symposium that same week, featuring student exhibitions from five different campuses around the state. The event, sponsored by the UNH College of Liberal Arts Global Racial and Social Inequality Lab (GRSIL) and the New Hampshire Humanities Collaborative (NHHC), focused on the idea of freedom through the lens of social justice.

For journalism students, the history of the GSO and its coverage in the media was particularly interesting.

For Bridget McSweeney ’24, the realization that despite progress made in equal rights, there is still work to be done was an important one. “People assume this was so much further in the past, but in some ways, it’s not — we’ve been researching the high number of anti-transgender bills currently circulating. So the homophobia and transphobia are still happening, but maybe just not as loud.”

Her classmate, April Towne ’25, agrees, noting that as a journalism student, it was fascinating to compare the media coverage in the student newspaper and other statewide outlets with media coverage of LGBTQIA+ issues today. In anti-trans legislation today, says Towne, there are “definitely parallels” to the way those who are anti-trans or anti-queer people construct their arguments.

The close-to-home nature of studying LGBTQIA+ rights through the lens of UNH history was engaging to her students, says Cashman — especially getting to chat with returning alumni like Paul Tosi ’74 and Wayne April ’74.

She says it was moving to see that the university was embracing the commemoration of the events. The legacy is one to celebrate, as President James Dean Jr. said at the breakfast, but still “a legacy rooted in deep adversity.”

“I’ll admit there was some question mark about what the reaction would be of the greater university community,” says Cashman. “But it became very clear at breakfast: The reaction was to celebrate how incredible these students in the early 1970s were, how brave they were and how they were able to see a future that no one else was seeing at the time.”