he day I was diagnosed with a rare spine cancer, I knew I had a problem, just not that problem. For the better part of a year, I had stripped away movements — from gym core routines I didn’t much like anyway to things I did, like raking a yard of warm compost into old winter soil. I told others that when I could no longer ride a bike, a lifetime passion, I would see my doctor to confirm what I already knew: I had a disk problem. Every 50-year-old I knew had some sort of lower-back ailment they didn’t do anything about. We were a league, stoic and proudly inattentive. In July of 2014, I couldn’t sleep or stand without having disabling waves of nerve pain running the course of my legs. I was off the bike. I made the appointment.

I knew they had seen something bad the moment the imaging techs slid me out from the white MRI silo. They had seemed distracted when I arrived. They weren’t now. Did I need more warm blankets? asked one. Something to drink? asked another. Is somebody coming to bring you home? They led me upstairs, where the head spine surgeon, a genial Irishman, showed me the image of a tumor type he had heard of but never seen in a patient. It was a softball-size mass affixed to my lower spine, billowing out north by northwest, distinguished by its lobed shape, which looked to my uneducated eye like the human brain. Dr. Terence Doorly stressed that nothing about this thing inside me — slow-growing, exceedingly rare, originating from leftover prenatal spinal cord cells — was run-of-the-mill.

Things moved quickly. One of the leading chordoma teams in the country was right here in Boston, at Massachusetts General Hospital. Three days later I was meeting with them. We overflowed a tiny examining room — surgeons, oncologists, fellows, nurses. A fellow in a white lab coat slipped in to offer a chemo-and-something clinical trial slot. Wait, was I that bad? Al, an RN care coordinator, diplomatically moved him along. Al wasn’t the nurse archetype I’d expected. He looked like the former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich.

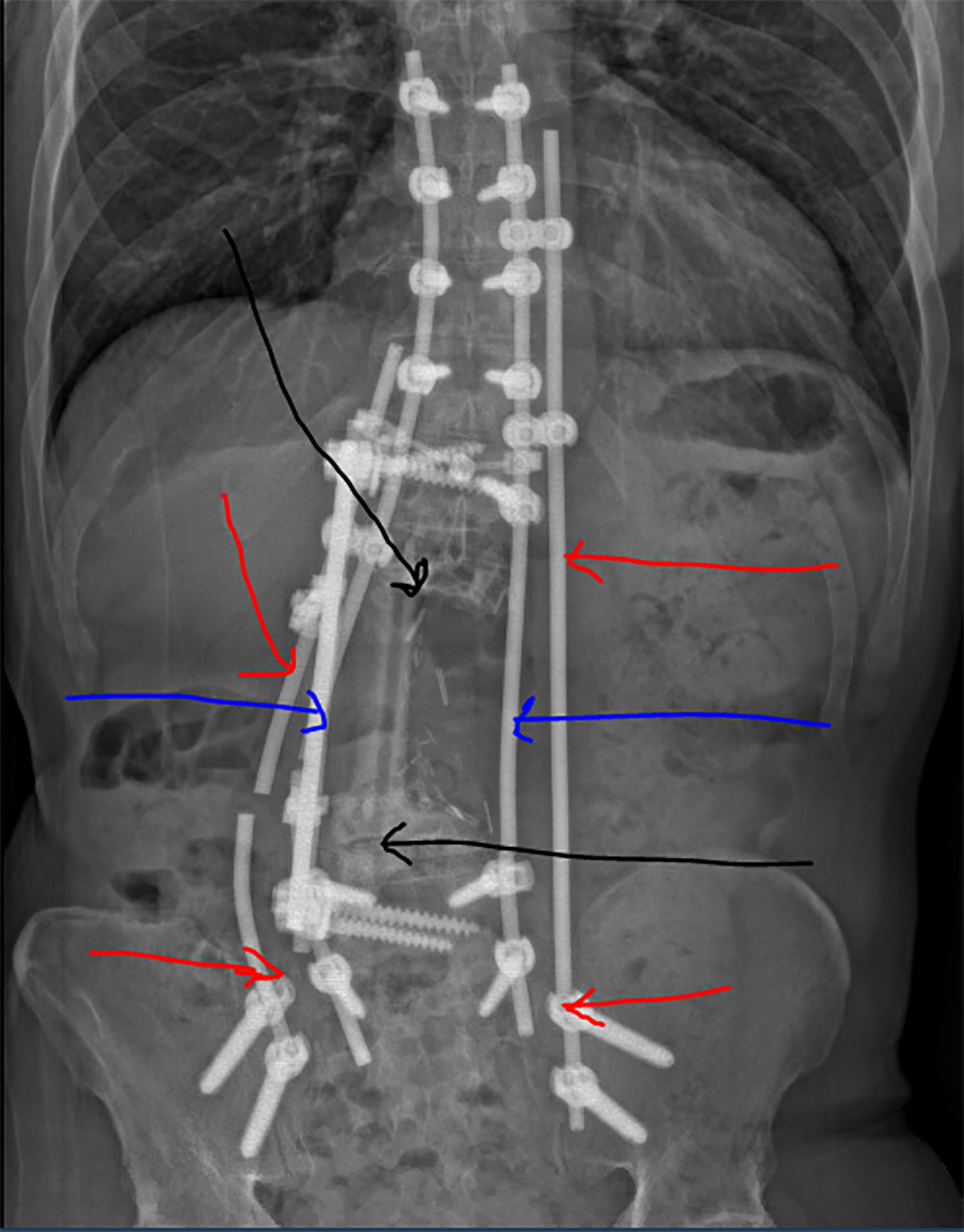

The chordoma team outlined a plan of daily radiation treatments for five weeks, followed by a short recuperation period, then surgery. Then a radiation top-off. The surgery involved two stages on separate days. First the team would go in from the front to put several spine-supporting rods in position. On the second day, they would flip me over to remove the diseased L2 and L3 vertebrae and muscle tissue from my right hip and briefly apply a radiation patch to a portion of the dura, the protective sheathing around the spinal cord. Another surgeon would harvest some of my right fibula, repurposing it to span the several-inch gap in my divided spine. Each surgery was expected to take eight hours.

I wasn’t supposed to be here. I led an active, healthy lifestyle. Never smoked. Bowed down to kale. Most people who learned what I did for a living told me that they wanted to do it, too. Traveling, seeing the world, writing about it in my barn-loft office overlooking a pocket-size vegetable garden crammed with tomato plants and snap peas. I had a great gig.

We had married a year after she graduated, and early on she had acquiesced to the adventures I urged on her: a nauseating high-altitude overnight in a dingy Quonset hut atop an active volcano in Guatemala; a remote Kokopelli mountain bike trail in Utah where she rode four-wheel support while pregnant; paddling on whitecapped Jackson Lake, in the Tetons, with months-old Celia in tow. This would be another adventure she really didn’t ask for. With our youngest child, our son Henry, off early to college for preseason soccer, we had been quasi empty nesters for four days. On day five, I came home with cancer.

The diagnosis, tests and assortment of specialists gave me the impression that I was gravely ill, soon to be wheeled into surgery, but instead the medical process played out slowly. The photon and proton radiation had to be designed, scheduled and delivered over months, a period of rest and pain management leading up to surgery. I wrote angsty, Thomas Paine-sounding notes to poor Al, with beseeching statements like “Time seems very much of the essence” and “I’m ready and available.”

In the interim, I went to my kids’ college soccer games, sitting on a series of frigid aluminum bleachers throughout New York State and New England. In Lowell, my brittle spine seemed ready to splinter in two when I rose to my feet. I had to be carefully helped through the parking lot, then into the passenger seat of our heat-blasting Subaru, where I took every pill in my pocket. When I asked for medical insight into the adverse interaction of ice-cold bleacher metal with a chordoma spine, Al said the literature was thin.

In October and November, spinal pain be damned, I rode a bike from the North Station train depot to my presurgery radiation appointments. A few weeks earlier, I had urgently observed in my journal, “I need a cancer bike … something portable, comfy, cool, likable, something that somehow defines the journey, loyal as a dog, smile producing, not exactly a friend but damn close. Needs some mojo, some ancestral oomph. What is it?”

It was a Boston bike-share bike, silver and black, with balloon tires and a wide, soft seat, step-through-framed for grannies and grade schoolers, and no more aesthetically appealing than a tray of hospital food. My one-kilometer commute between North Station and the Francis H. Burr Proton Beam Therapy Center was short but not without hazard. The gap between my tumor and my touchy spinal nerves was razor thin. By any measure, riding the jarring, unprotected streets of Boston was a ridiculous risk. Maybe I was howling against cancer; maybe I simply adored being back on a bike, even for just six-tenths of a mile. When I walked into the waiting room for the first time, I let my helmet dangle on the outside of my messenger bag like I wouldn’t mind someone noticing.

Things moved quickly. One of the leading chordoma teams in the country was right here in Boston, at Massachusetts General Hospital. Three days later I was meeting with them. We overflowed a tiny examining room — surgeons, oncologists, fellows, nurses. A fellow in a white lab coat slipped in to offer a chemo-and-something clinical trial slot. Wait, was I that bad? Al, an RN care coordinator, diplomatically moved him along. Al wasn’t the nurse archetype I’d expected. He looked like the former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich.

The chordoma team outlined a plan of daily radiation treatments for five weeks, followed by a short recuperation period, then surgery. Then a radiation top-off. The surgery involved two stages on separate days. First the team would go in from the front to put several spine-supporting rods in position. On the second day, they would flip me over to remove the diseased L2 and L3 vertebrae and muscle tissue from my right hip and briefly apply a radiation patch to a portion of the dura, the protective sheathing around the spinal cord. Another surgeon would harvest some of my right fibula, repurposing it to span the several-inch gap in my divided spine. Each surgery was expected to take eight hours.

I wasn’t supposed to be here. I led an active, healthy lifestyle. Never smoked. Bowed down to kale. Most people who learned what I did for a living told me that they wanted to do it, too. Traveling, seeing the world, writing about it in my barn-loft office overlooking a pocket-size vegetable garden crammed with tomato plants and snap peas. I had a great gig.

We had married a year after she graduated, and early on she had acquiesced to the adventures I urged on her: a nauseating high-altitude overnight in a dingy Quonset hut atop an active volcano in Guatemala; a remote Kokopelli mountain bike trail in Utah where she rode four-wheel support while pregnant; paddling on whitecapped Jackson Lake, in the Tetons, with months-old Celia in tow. This would be another adventure she really didn’t ask for. With our youngest child, our son Henry, off early to college for preseason soccer, we had been quasi empty nesters for four days. On day five, I came home with cancer.

The diagnosis, tests and assortment of specialists gave me the impression that I was gravely ill, soon to be wheeled into surgery, but instead the medical process played out slowly. The photon and proton radiation had to be designed, scheduled and delivered over months, a period of rest and pain management leading up to surgery. I wrote angsty, Thomas Paine-sounding notes to poor Al, with beseeching statements like “Time seems very much of the essence” and “I’m ready and available.”

In the interim, I went to my kids’ college soccer games, sitting on a series of frigid aluminum bleachers throughout New York State and New England. In Lowell, my brittle spine seemed ready to splinter in two when I rose to my feet. I had to be carefully helped through the parking lot, then into the passenger seat of our heat-blasting Subaru, where I took every pill in my pocket. When I asked for medical insight into the adverse interaction of ice-cold bleacher metal with a chordoma spine, Al said the literature was thin.

In October and November, spinal pain be damned, I rode a bike from the North Station train depot to my presurgery radiation appointments. A few weeks earlier, I had urgently observed in my journal, “I need a cancer bike … something portable, comfy, cool, likable, something that somehow defines the journey, loyal as a dog, smile producing, not exactly a friend but damn close. Needs some mojo, some ancestral oomph. What is it?”

It was a Boston bike-share bike, silver and black, with balloon tires and a wide, soft seat, step-through-framed for grannies and grade schoolers, and no more aesthetically appealing than a tray of hospital food. My one-kilometer commute between North Station and the Francis H. Burr Proton Beam Therapy Center was short but not without hazard. The gap between my tumor and my touchy spinal nerves was razor thin. By any measure, riding the jarring, unprotected streets of Boston was a ridiculous risk. Maybe I was howling against cancer; maybe I simply adored being back on a bike, even for just six-tenths of a mile. When I walked into the waiting room for the first time, I let my helmet dangle on the outside of my messenger bag like I wouldn’t mind someone noticing.

I felt as mentally and physically robust as a man carrying a tumor inside his spine could. I looked forward to the surgeries to come, when the world’s foremost chordoma doctors would excise the tumor, at which point I’d get back to being me again. I liked all the players on my new team, especially the lanky, white-haired radiologist Tom DeLaney. His son was a college athlete, like my daughter and son, and he was a fan of adventure travel, just back from a river trip on the Colorado. When he asked about my writing, I sensed a spirit comrade. I gave him a signed book of mine about a pioneering descent of Tibet’s Tsangpo River, and he seemed seriously pleased. I was, too. Rather than being patient number 5465197, I thought I had established myself as “Todd, the crazy guy who should live and ride his bike again.”

On the eve of my surgery, Patty and my older brother Tom sent out a note to friends. They explained the impending surgery and asked those who could to grab a bicycle the next day and go for a ride. “We can’t think of anything in this universe that would be more meaningful and supportive of Todd,” they wrote. A bunch of people did it: my daughter and son and their friends at the University of Albany and Boston College, respectively; Patty, who in the middle of that terrifying day snuck into the hospital’s gym with her sister and her best friend, all of them dressed for the office; my grade school friend Kip, a Brookline pastor, who rolled into the hospital waiting room on his mountain bike, soaking wet from one of the day’s downpours. My lifelong friend Jackie, a neophyte rider, could only get hold of a neighbor’s fancy road bike with clipless pedals. At the first stop sign, she forgot she was locked in and keeled right over.

I bled significantly from the aorta and the vena cava, and a little more when the feeder veins fueling the bloated tumor were cut free. My slight frame and shallow body cavity made an already tight working space smaller. The chief surgeon would later tell me I was a much harder case than they’d anticipated, and that patients with my level of severity had only a 1-in-10 survival rate. The tumor removal required three surgeons working together before they could safely lift out the mass and pass it on to pathology. Dr. Sang-Gil Lee delivered 10 centimeters of my right fibula to Drs. Hornicek and Schwab, who fused the bone to its new structural home along the spine. The fixing of the supporting rods and struts finished the job.

An X-ray of my Erector Set back was a wonder to behold. I have a picture of it on my phone. Five surgeons were involved at one point or another during my second surgery, as were assorted nerve specialists, anesthesiologists, nurses and radiologists. Early in the evening I was wheeled into ICU recovery, where I was pronounced in satisfactory condition. Tom, who had unfailingly guided me through teen breakups and middle-age meltdowns, remembers the chief surgeon’s exhausted face when he reported to my family in the waiting room. He looked like he had been in a no-round-limit MMA fight.

The following day, still heavily sedated, I told Patty and my brother about the pleasant visions I was experiencing and requested a drawing pad, expressing the confident desire to paint watercolors like my late artist father had. I couldn’t really sleep, but I was pain-free. When my neighbor Tim smuggled in a J.P. Licks milkshake, I slurped away.

In all the months I had been walking around in pain, I never felt disabled. I was injured, not disabled. Injured and now fixed. Here’s the moment when I first realized that things might be different than I expected: I was on the edge of the hospital bed, a nurse and a physical therapist on either side ready to help me to my feet for the first time. The doctors’ instructions were to get me up as soon as possible.

“Can we let go?” they asked. Before all this, I had thought of myself as one of the fittest people my age. Only nine months earlier, I had hiked and biked from Stratford-upon-Avon to East London, where, with a 20-something Fleet Street travel writer riding double on my seat, I gleefully bore down on the pedals to climb the entrance ramp to the newly built stadium at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

I smiled confidently as they pulled their hands away. But there was a void in the place where my legs should have been. They were there, but they weren’t. I was falling.