avid Kaye worked with students over Zoom to rehearse and then present an adaptation of the play “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” which should have opened live on campus in 2020 just after spring break.

Rachel Campagna offered remote one-on-one office visits where she asked students to tell her one boring thing about themselves in an effort to get to know them. Fifty out of 70 students signed up.

And Gregg Moore created virtual field trips for students who, in normal times, would have been right there with him in the bogs, marshes and dunes captured in his videos.

Some of those changes evolved instinctively. Some required new ways of thinking to advance new ways of learning. Some admit there were moments that felt like they were winging it, throwing away the playbook. All met the challenge, some grabbing hold with both hands. Teach students about the stars when “remote” meant Zoom classes and not how far away the galaxies are? Stage a theatrical production without the cast together on stage? You bet.

That spring semester and then into the fall, there were revelations that confirmed for faculty members what they are good at, and what newly learned practices they could add to their teaching toolkits that would make them even better. Things they only could have realized within the clamped-down pandemic environment. In the end — or what today looks more like an end than anyone would have thought possible a year ago — they were able to find the positive among the chaos the virus bred.

Kaye found out how by turning to his peers, those who had expertise in areas he did not; colleagues he had often thought of bringing to UNH to present workshops, but travel and other expenses had made cost-prohibitive. In the new world of virtual meetings, that issue was resolved.

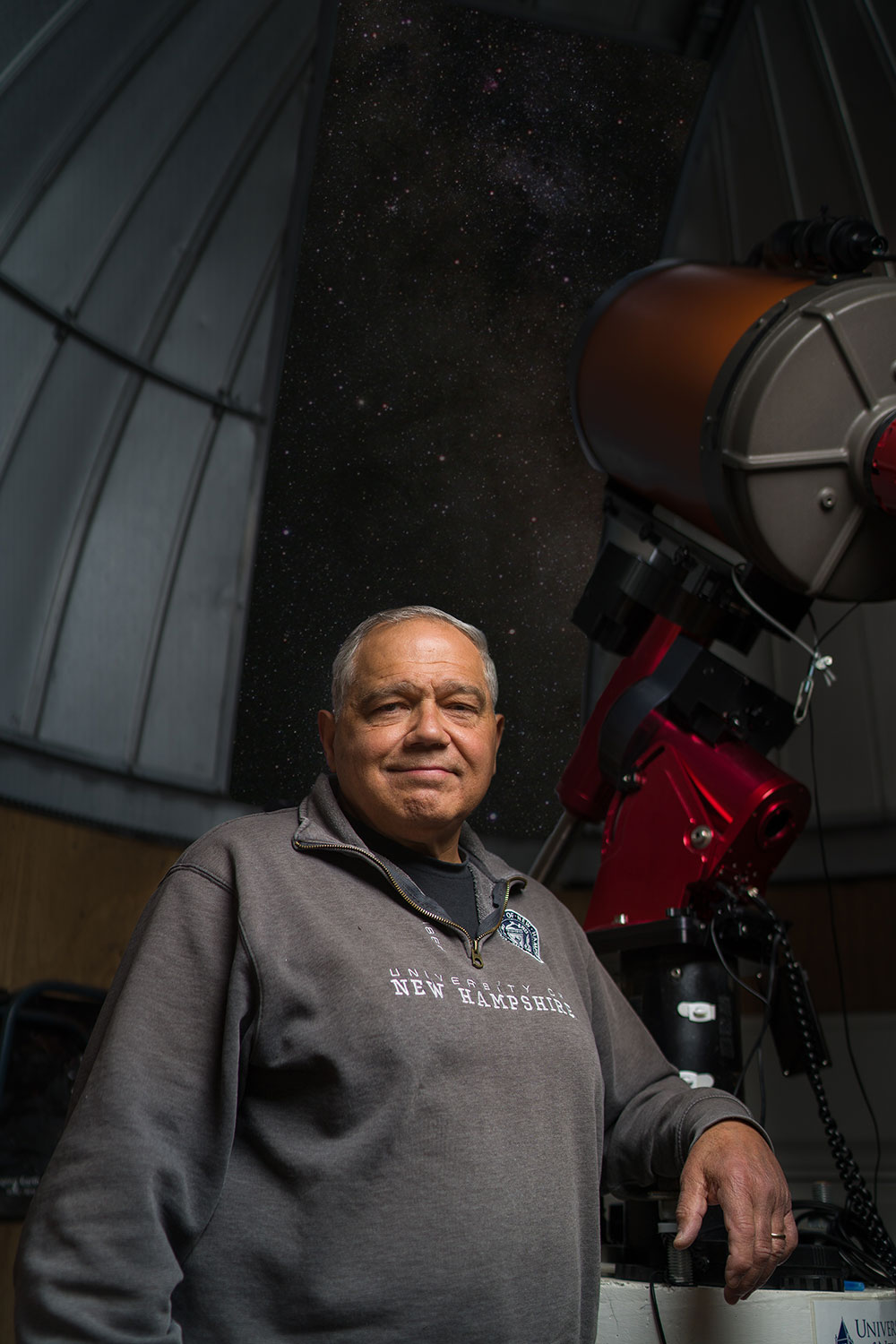

Astronomy instructor John Gianforte is the director of the UNH Observatory. Because he had previously taught courses online, he was quick to adapt when UNH went remote, recording his lectures and using Zoom to answer questions. He also utilized discussion boards, where students could talk about almost anything. But how to replicate the work they did in labs?

Gianforte found the answer in telescopes. Big ones. The kind used in observatories around the world. During the summer of 2020, at his urging, the physics department bought a membership for two such telescopes, one in Chile, the other in the Canary Islands. Students could go online and use the telescope for five minutes at a time, observe the sky and take a photo that was later sent to them to study.

“It was most challenging for those online. Because of the way the classroom cameras were focused, it was more difficult for students who were remote to see the students in the classroom than their peers who were also online,” she says. “I had to try and juggle the screen space. With remote, you miss the body language, the energy you can sense when you’re all in the same room. The most important thing I learned during the pandemic was to be flexible. And then, to be more flexible.

“This is not the same as abandoning or even dropping standards,” Dorsey says. “It isn’t even something that only faculty need to do; students need to be more flexible also. But from a teacher’s perspective, this means being willing to experiment with the way you teach during the semester, willingness to change your lesson plans in the middle of class, and willingness to be more explicit than usual about decisions you are making.”

All things that she and other UNH faculty did. Within days. But those speedy adjustments may have valuable long-term benefits, as faculty members choose which parts of remote instruction to keep going forward.

With the help of his own family and a graduate student and her husband, Bell also made a number of videos showcasing emergency situations where, using Zoom breakout rooms, students had to make a diagnosis. Then, when in-person learning resumed in the fall, Bell started holding his classes outdoors and has continued to do so throughout the spring semester.

“I found myself flipping my classroom by assigning homework that consists of watching short lecture presentations that allow students to engage with the course material asynchronously. Then my class time outside is almost all problem-solving, group work and discussions,” Bell says, adding he plans to continue teaching in this way. “I think part of the lesson for me was to not depend so much on assigning work but to provide more space for students to talk about ideas. Good for the students and really good for me, too.”

Campagna, assistant professor of business administration, believes that what has been good for her students was creating an open culture where they felt safe. As a member of a group of women academics in organizational behavior, Campagna relied on her colleagues’ perspectives to teach online.

She employed a survey to get a sense of technological challenges and asked students how they were doing in general. She then set expectations and instituted a norm of flexibility, calling her syllabus a “flex-genda.” And she kept her lectures to under 10 minutes.

“I knew my students were anxious and overwhelmed and scared and disappointed,” Campagna says. “My goal was to keep them engaged so they could forget about what was going on around them. They were very open and honest, and I saw them struggle. I empathized and told them to reach out if they wanted to talk about anything class-related or anything in general.”

That’s where the one-on-one virtual office visits came in.

“I got to know them on a personal level. I think establishing that relationship was the most critical thing I could have done for my students and the class culture,” Campagna says. “The teaching principles helped, but this was really where I felt I did my best to meet their academic and personal needs.”

“All of a sudden, there was this creepy life crawling all around in the video,” he says. “Students aren’t going to remember what they read on page 32 of the textbook but will if they handled it, broke it open, smelled it. I had to make that happen using a camera. It was pretty effective.”

Here’s proof: One student evaluation read ‘You were the only person who tried to keep some normalcy.’ Another said, ‘You were nuts, but it was great.’

That long view — the more than 15 months since COVID-19 shut down UNH — has shown him, and others, the good that has come from the forced changes. Good things they will carry forward.

“As someone who deeply values hands-on, immersive, and field-based learning, I would have never intentionally planned to create online learning content,” Moore says. “While it will never replace in-person learning for me, there’s no question it has tremendous value.”

That value still struck Kaye as hard to simulate. He knew earlier this year that a live production with a live audience wouldn’t take place at UNH’s Hennessey Theatre even with students back on campus. It would have to be via Zoom again, or outside wearing masks.

“In the end, I feel this past year, despite the intense challenges, held its own unique power. An actor must continually read behavior on stage to respond to it fully, truthfully and spontaneously,” Kaye says. “Having only the eyes available to read their stage partner’s face forced them to learn how to get the maximum impact from a minimal amount of visual information. Imagine how much easier it will be for them, having strengthened these observational muscles, when they can react to the sight of entire human face.”

“I told them, guess what? You won’t be stressed about that now. You’ll also have flexibility in learning what you need to know,” she says, adding, “Some people have called this a lost year, but I think in terms of it being a different year, a year when students learned things they wouldn’t normally learn.”

“I think I was more caring for the unknown and unseen stresses that students may be experiencing,” Bell says. “I have always tried to balance support and challenge in my classes. This year I focused more on supporting students than challenging them, and in the end, I think the pandemic may have helped to show me how much support is needed to get the best out of students.”

And it may have shown faculty how to get the best from themselves. In April, Campagna taught a portion of her hybrid graduate-level negotiation course in person. She hadn’t interacted with 30 people at a time for more than a year. Thinking she’d be nervous, she started the class with humor.

“I told them I hadn’t worn real pants in over a year and asked who else was wearing real pants for the first time. Only about seven people raised their hands,” Campagna says. “After the first break, a student came up to me and told me I was doing a great job, that he basically hadn’t interacted with anyone in over a year, and that he was very nervous to the point of visibly shaking.”

And that experience is something she will remember for the next class. And the next.

During the last year, OT students who were scheduled to do internships at hospitals, clinics and other commonly used sites saw them canceled. Before going fully remote, labs were limited to six students in pairs of two. After that, faculty prerecorded videos, created asynchronous content and mailed lab materials/samples to students’ homes.

“Our priority was to ensure students graduated on time, so we changed their course sequence and offered some of their post internship courses sooner and flipped their semester,” Arthanat says. “They had to make changes but somehow everyone adapted to make it work.”

And there it is, that can-do attitude: UNH faculty and students in it together. Stronger; more flexible. Making it work.