and

Science

e’ve all read stories about individuals who become briefly capable of superhuman feats when faced with a threat to their loved ones — in the classic example, it’s the mother who singlehandedly lifts a car off her trapped child. There’s a name for the phenomenon — hysterical strength — and a theorized explanation: a flood of hormones including adrenaline, cortisol and endorphins that is released in response to extreme stress and allows muscles to tap into their maximum strength even as it blunts the brain’s perception of pain.

As showy as it is, hysterical strength is also fleeting; the mother who lifts the car up can’t do so for more than a few seconds. It takes an entirely different kind of superhuman strength to face a threat that’s settled itself in for the long haul. A chronic illness, for example, or a life-limiting one. A disease your child has just been diagnosed with that’s so rare it not only has no known treatment, its cause and mechanism aren’t even fully understood. So rare, in fact, you haven’t even heard of it yourself, even with your newly minted Brown University M.D. and Ph.D. in neuroimmunology in hand.

Today, progeria is understood to be caused by a genetic mutation that creates a protein known as progerin, which destroys the nucleus of healthy cells; in late 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first known treatment for progeria, which works by arresting the production of progerin and has been shown to add an average of 2.5 years to the lifespan of children with the disease. These two remarkable milestones toward a cure for progeria are in large part the work of Gordon, who resigned from her medical residency when Sam was diagnosed to instead devote herself to finding the cause of his illness, a potential treatment, and ultimately a cure.

If that seems extraordinary, to Gordon, it was the most obvious thing in the world. She puts it succinctly in a TED talk she gave in 2013, pacing the stage in a cranberry-colored pantsuit as she shares her philosophy on how to achieve any goal imaginable:

“What do you do when there’s nowhere to turn?” she asks. “You drive straight ahead.”

After graduation, she spent several years working in a lab at Boston University, where she met her husband, Scott Berns, M.D., M.P.H., FAAP, then a student at the Boston University School of Medicine. From BU, she went on to earn a Master of Science in physiology at Brown University and then, unsure whether she preferred research or clinical medicine, enrolled in a joint M.D./Ph.D. program at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School so she didn’t have to choose. Gordon took a residency in ophthalmology at Mass Eye and Ear in Boston, accompanied by an internship year in pediatrics at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, and the couple married in 1993. She had completed her M.D. and was writing her doctoral thesis on the immunological treatment of a type of brain tumor in mice, preparing for a career in pediatric ophthalmology, when Sam was born on Oct. 23, 1996.

Like the majority of children diagnosed with progeria, Sam appeared healthy at birth. By the time Sam was 9 months old, however, his two pediatrician parents became aware that their infant son’s growth had slowed, and he had yet to cut his first teeth. Shortly after that, Sam’s hair began to fall out. Despite their knowledge and their contacts, Gordon and Berns were unable to pinpoint the cause of Sam’s physical changes — nor could the various specialists they consulted. Eventually, a friend who was a pediatric intensive care physician in Boston suggested that Sam might have progeria, and the couple requested several clinical tests, including x-rays, that supported a progeria diagnosis. A consultation with a doctor at the New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities in Staten Island, then the foremost progeria clinician in the United States, confirmed their worst fears.

“At the time, there was almost no information out there about progeria,” Gordon explains. “I had not heard of it at all in medical school.” What was known was that a cluster of symptoms, first identified by British surgeon Jonathan Hutchinson in 1886 and corroborated by his countryman and fellow surgeon Hastings Gilford 11 years later, led to a relatively predictable sequence of developments: cardiovascular disease as early as age six, atherosclerosis, and death by heart attack or stroke at an average age of 14.

Progeria has no ethnic or gender bias — it’s been documented in countries across the globe — and by the time they are elementary-school-aged, children with progeria share a set of distinguishing features. Significantly shorter and slighter than their peers, they have large, bald skulls that feature prominent veins through thin skin, and distinctively narrowed noses. Without exception, children with progeria develop premature atherosclerosis, with increasingly stiff blood vessels and vascular plaques that put them at risk for heart attacks and strokes. Importantly, however, although children with progeria appear many decades older than they are and are diagnosed with ailments commonly associated with aging (the name progeria comes from the Greek words pro — before—and geras, old age), they are very much children in all other regards, with the same interests, personalities and intellectual capabilities as their schoolmates.

Asked to reflect on the remarkable fact that she, her husband, and her sister were exactly the right people with the right skillset to undertake such an effort (in addition to holding a medical degree, Berns has a master’s in public health from Harvard; Audrey Gordon’s law degree made her a perfect fit to serve as the foundation’s president and fulltime fundraiser), Gordon is philosophical.

“We did what any parents would do,” she says. “We learned what we had to learn along the way.” In a 2014 profile in Brown Alumni Magazine, she put an even finer point on it: “I know I may not succeed in saving Sam’s life, but I could not live with myself if I didn’t try.”

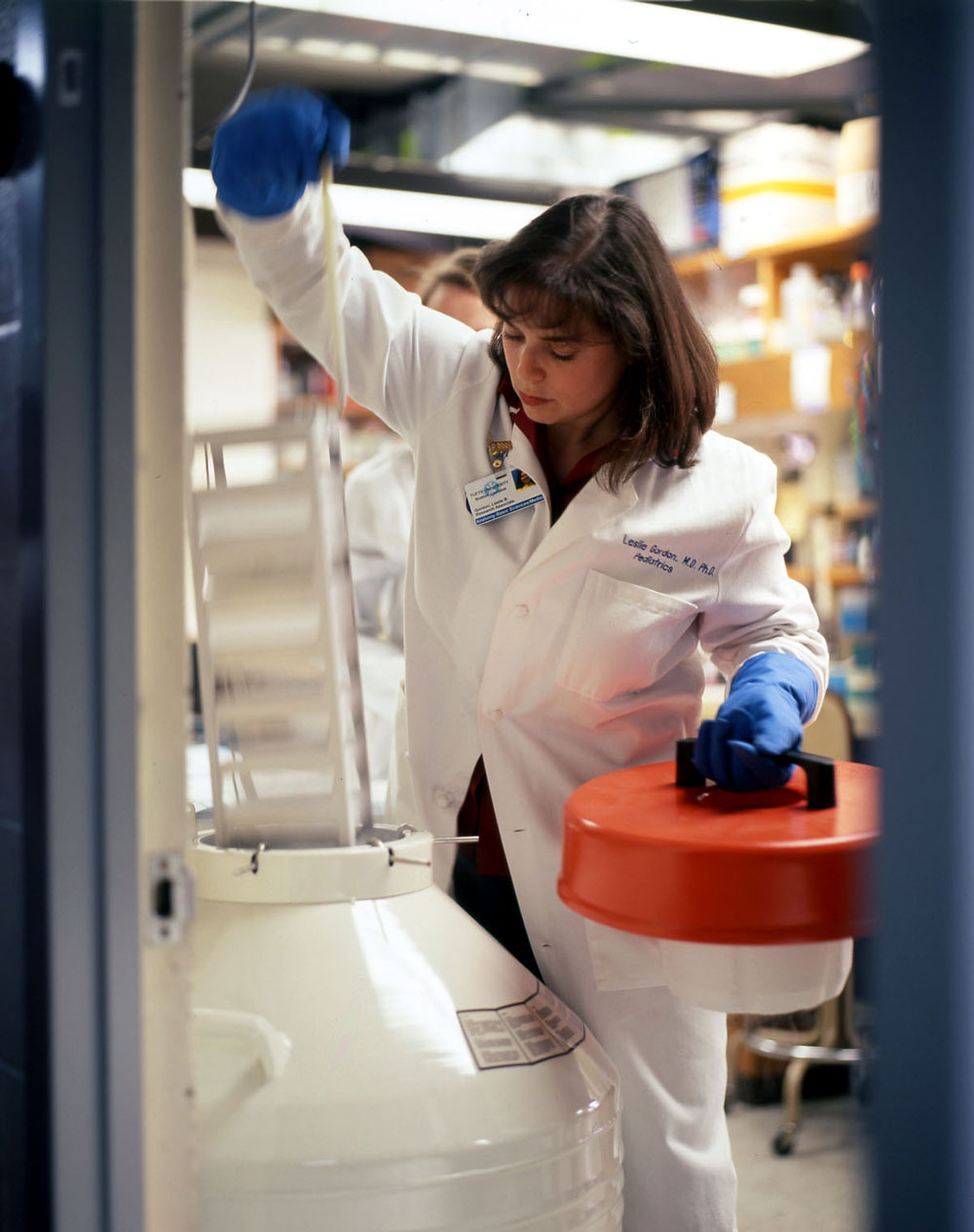

Gordon says the basic research chops she first developed at UNH and subsequently honed at BU and Brown came in handy as she rolled up her sleeves and got to work, supported by a small group of researchers with expertise in the areas of genetics and aging. So did her outreach to Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., today the director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) but at the time the director of the National Human Genome Research Institute. Years earlier, Collins had a patient of his own, a girl named Meg, who exhibited symptoms indicative of progeria. Having led one of the teams that was in the midst of successfully completing sequencing the human genome, Collins was eager to apply what was being discovered to the treatment and cure of different diseases. In early 2003, he succeeded in identifying the progeria gene, working as part of a five-laboratory consortium Gordon had assembled and with cells and blood samples that Gordon supplied through the progeria cell and tissue bank she had created.

With record speed, Gordon and teams of collaborators tested these drugs on cells and a newly established progeria mouse model, and in 2007 launched a two-year clinical trial of an FTI called lonafarnib, fully funded by The Progeria Research Foundation, that involved 28 children with progeria ranging in age from 3 to 16 and hailing from 16 countries. Sam Berns, of course, was among them.

Gordon politely demurs when asked to share her thoughts on what her son, age 11 at the start of the lonafarnib trial, might have thought about the fact that his mother had been the driving force behind a major medical breakthrough with the potential to rewrite the future of children with progeria, all because of him. But in a 2013 HBO documentary, “Life According to Sam,” the then-teenaged Berns reflects on that very question with a level of insight that belies his years. “I kind of just want my mom to be done with progeria, for her sake,” he says. “She doesn’t have a normal job .… It’s not the kind of job where you go in, you do what you’re supposed to do, you get paid, and you can leave whenever you want, at your own risk. My mom will keep working until progeria is cured — forever.”

But the documentary also doesn’t shy away from the toll progeria takes on Sam, whose marching band dreams are tested by the weight of his equipment and the on-field jostling that could lead to fractures of his progeria-weakened bones, and who at one point laments the manner in which a week of clinical-trial-related testing at Boston Children’s Hospital isolates him from everything about his life that isn’t his disease. And while “Life According to Sam” shows Sam and Gordon getting the same good news about the clinical trial as other participants — two years of lonafarnib have improved the elasticity of his carotid arteries, lowering his chance of stroke — Gordon’s race against time to save her son ended on Jan. 10, 2014, when Sampson Gordon Berns died of progeria. He was 17 years old.

Reflecting on not only Sam’s life but the lives of a heartbreaking number of children with progeria she’s met through The Progeria Research Foundation, she says, “There are children throughout the world who have sacrificed an awful lot so that other children can benefit. I always say that once you’re in, you’re in. And we absolutely owe it to every child with progeria throughout the world to be with them and work our hardest every day for them, and that’s just the way it is.”

Indeed, Gordon continues to work her hardest every day — as does husband Scott, a pediatric emergency physician and CEO of the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality who serves as PRF’s chairman of the board, and sister Audrey, who is PRF’s president and executive director, and Gordon’s Boston Children’s Hospital clinical trials coinvestigator Monica Kleinman, M.D., who was the first to suggest Sam’s diagnosis back in 1998, and countless others who have dedicated their time and talents to finding a cure for progeria.

Gordon and Kleinman’s 2007 lonafarnib trial demonstrated that after two years of treatment, one in three children experienced meaningful weight gain or had stopped losing weight, and more than a third showed decreased blood vessel stiffness — promising results that paved the way for a second study of lonafarnib with an expanded patient population of 62 children. Results of that subsequent study indicated an increased lifespan of 2.5 years — an astonishing 20% — for children treated with lonafarnib, and led to FDA approval of the drug, under the brand name Zokinvy, as the first-ever approved treatment for progeria. Progeria is now one of the few rare diseases to have an FDA-approved treatment.

“So do I think we’ll find a cure for progeria?” she says. “I do. But we don’t stop and say ‘we’ve got the cure’ when we don’t yet. We fund, promote, collaborate and push forward on any type of therapy that we think is viable and might lead to something.”

It’s hard to imagine any of this happening had Sam Berns not been born to a couple of medical doctors, and more specifically, to Leslie Gordon, a pediatric specialist and bench scientist.

And yet, asked for her thoughts on what seems like the almost fated nature of her path, Gordon steers away from destiny, the idea of superhuman feats, and even science to reach instead for a sentiment that seems remarkable and relatable all at once. “I don’t know about that,” she says. “I just know I was lucky, getting to be Sam’s mom.”