The Class

of 2022

Looks Back

Photography by Jeremy Gasowski

n a few weeks’ time, UNH seniors will be filing their intent to graduate forms —the formal paperwork that signals the completion of their undergraduate degrees. Once filed, credits will be counted up, GPAs tabulated, caps and gowns ordered. It’s a rite of passage each May, but when this graduating class, the roughly 2,600 members of the Class of 2022, walks across the Commencement stage this spring, it will be the culmination of an undergraduate experience unlike any other in UNH’s history.

This is the class of students who know the before-pandemic normalcy of their freshman year, and who have been adjusting to varying “new normals” each year since. As the pandemic has extended from a two-week lockdown in spring 2020 to a two-year reality in 2022, its longevity has meant that the typical life of a college student has come to include as many nose swabs and masks as it has traditionally held long study hours and weekend parties. During that time, protests against social injustice and racism, and rising political divisiveness have also taken root, increasing the challenges for college-aged students.

Through it all, UNH has remained open for business, even when it was emptied of students for a semester, and then shifted to a hybrid model of on-campus living, remote learning and adjusted schedules before eventually going back to fully in-person classes. That success is thanks in large part to a state-of-the-art COVID lab created in just about three months in the summer of 2020, a robust testing program that continues today, and a public health campaign followed by the campus community to limit infections on campus.

So how has the Class of 2022 weathered it all? We asked a few seniors to share their thoughts on their experiences. But first we checked in with campus leaders who have seen senior classes come and go, but who all agree: This was an undergraduate experience like no other.

“Our students likely won’t experience anything like this again in their lifetimes,” says Kenneth Holmes, senior vice provost for student life. He said some students have talked about the feeling that they’ve lost community or a sense of belonging, due to pandemic isolation. The problem is that they don’t see themselves as successful, says Holmes — but he believes the exact opposite is true.

“I think students are thankful that they made it to graduation, and that they are graduating on time,” said Holmes.

Erin Sharp, associate dean in the College of Health and Human Services, and an associate professor of family studies, explains that college has always been a time of transition for students ages 18 to 21, a physical and emotional break away from family as a normal part of their development from adolescence into adulthood. Some level of stress and anxiety has always accompanied this developmental stage — to put it simply, change is hard. But when the pandemic hit — and lingered — those stresses were exacerbated greatly.

Not only did their college experience change in unprecedented ways, but the job market they’ll be entering is equally unusual — but with some positive outcomes. Thanks to the Great Resignation and remote work, more jobs are open to recent college grads, and young 20-somethings have more leverage than before in terms of perks and benefits. As the economic impact of the pandemic eases, says Trudy Van Zee, associate vice president for Career and Professional Services (CaPS), her office is hearing more from small- to mid-size companies struggling to find talent — which can be good news for recent college grads.

As a result, she points out, companies are expanding what they look for in a candidate, just as students are building their professional skill sets — an engineering firm might look beyond just engineering majors for roles they are trying to fill, for example.

“What that means for our students, and the message we try to get to them earlier in their college careers is that they will own their long-term security by building those skill sets to include critical thinking, adaptability, problem-solving skills … those deeply human skills valuable in any field,” she says.

From the CaPS perspective, the remote-work revolution has been the most dramatic change in the job market for graduating seniors, and that work location is just one of the many “negotiables” for students entering the workforce. “Job seekers are in a power position in a lot of industries, so that they are able to be a bit more selective, have conversations about benefits like flexible schedules and remote work,” says Tyler Wentworth ’08, CaPS director of marketing, communication and engagement. Interestingly, he finds that UNH students want to work in a hybrid workplace — some time from home, some time in an office or on-site.

“Most of them feel like they did enough sitting front of their own computers during the remote learning of the pandemic. They want to be around other people.”

For the seniors who spoke with UNH Magazine, the last three years of their undergrad experiences have been a mix of bright spots, dark moments, hope and perseverance.

Jasmine Taudvin

hen the pandemic hit, Jasmine Taudvin ’22 was studying at Regents University in London, where the student body is made up of roughly 80% international students. When she learned she would return early to the States, she had just begun her final project — interviewing 30 students from 17 different countries about what they remember being taught about certain historical topics: World War II, the American Revolution and the Silk Road.

For the Gray, Maine, native, learning about other cultures in this way was eye-opening and fascinating — and it would set the stage for understanding the global impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic over the next two years for Jasmine.

After trying out a few different majors in her first three years, Taudvin landed on a dual major of journalism and international affairs.

“With the Trump presidency, the Black Lives Matter movement and the pandemic … all those affected my approach to storytelling in different ways,” says Taudvin. “The clashing of all of that was the catalyst in figuring out what I want to do with my life — I’ve always been interested in art and activism. A lot of things I’m interested in making stories about are cross-cultural in some way — particularly showing how the U.S. affects other countries in a way I think a lot of people just don’t think about. I think now more than ever, those stories … it’s so important to be telling those stories.”

Part of that marriage of storytelling and activism took shape in the work she did for Black History Month, as part of the Culture Keepers, Culture Makers program run by Richard Haynes of UNH Admissions, Kristen Butterfield-Ferrell, who at the time worked in the UNH Honors Program, and Alyson Ryder, assistant director of UNH’s Community, Equity and Diversity Office. The program brought together five students in a discussion about race relations at UNH and identity and translating those discussions into art. Taudvin recorded interviews with the participants.

At UNH, she’s a Hamel Scholar, and is a resident assistant — last year in Hubbard Hall, this year in Congreve. She’s carrying a heavy load of courses for a senior and takes part in UNH Chorus as often as she can. Of the “new normal” of the pandemic, she says the hardest part was feeling isolated.

“Slowly, as we’re coming out and into this weird in-between state of things, I think I’m starting to come back out of that a little bit. It’s a weird cycle of energy; I know I need a lot of social interaction to feel OK, but I’m also so depleted by talking to people now, I just don’t have the energy. I suddenly realize I have a social battery I never had before; it gets runs down and need to recharge.”

But she sees that as somewhat of a silver lining. “Maybe it’s a good thing it showed up,” she says, adding that learning how to recharge and practicing self-care has been a positive.

That focus on mental wellness is another positive side-effect of these past two years. Her family has always talked very openly about mental illness because of a family history, and in high school she lost a close friend to suicide. She made it a point to visit UNH’s Psychological and Counseling Services office a few times. And the calls to her parents increased from once in a while to three or four times a week.

“Having someone to talk to where you don’t have to talk helped me so much,” says Taudvin. Another form of support came from her love of music.

During the more isolating times of the pandemic, when student-musicians couldn’t rehearse in large groups, she said having musicians on lock down in Hubbard was actually a blessing.

“During that whole year, you would hear music floating down the hall the whole time. There’d be one girl playing violin, another guy playing jazz saxophone,” she recalls. “Just to hear it constantly felt like a little piece of a Parisian café in Hubbard. I sort of miss that, honestly.”

Bryson Badeau

hen Bryson Badeau ’22 parks outside the Paul Creative Arts Center in his girlfriend’s car, it’s hard not to notice his bumper sticker: “I hope something good happens to you today,” it reads.

And it seems for his fellow UNH students, the “littles” he teaches at Village Nest Cooperative in Eliot, Maine, and even just people he’s walking past on campus, he is just that — smiling and waving hello as he walks into the Paul Creative Arts Center, where he spends a majority of his time as a secondary theatre education and design & theatre technology dual major.

“I like to think about the broader picture and look on the positive side. There’s so much negativity in the world, what’s one more negative person going to accomplish?” he says.

He’s so positive, in fact, that the word he uses to describe the past two years is surprising:

“Heavy. That is definitely the No. 1 word that comes to my mind. Politically, economically, the pandemic, and that’s on top of everybody’s day-to-day life dealing with things,” says Badeau.

Despite the challenges of the last few years, the Dedham, Massachusetts native says his love for theatre and his close-knit family — his mother and twin sister — are what helped him weather the uncertainty.

“Me, my mother and my sister are very close, so the time I was home, we were stuck like glue to each other pretty much. I got so used to being around my family, then we came back to campus, and everything was like walking on eggshells. I had a single, so I didn’t have a roommate to socialize with,” he says. That’s when theatre became his focus. “I really throw myself into theatre. This year I’ve been auditioning for every show I could be in and working as a technical assistant in the Theatre Program almost every day. That has been substantially better — going to work every day and seeing people in public. I live in the PCAC pretty much.”

When he’s not at the PCAC or representing the College of Liberal Arts as a COLA Fellow, he’s at Little Nest Cooperative, a school and childcare center in Eliot, Maine. He says working with children there — who range in age from preschoolers to second-graders — has put some of the divisiveness he sees in perspective.

“At the school, we encourage figuring things out by talking about what they’re feeling. I do wish we as adults and older people could revert back to that: We can have differing opinions and it doesn’t have to be the end of our relationship, as long as we agree on some basic human rights. These little kids are more capable of talking their feelings out to each other than we are!”

Badeau is in the accelerated master’s program, so he will be at UNH for one more year. He’s been offered the position of artistic director at Village Nest after he graduates. From there, he says “I think I’ll definitely end up in a high school, and I’d love to build an afterschool theatre program. Ultimately, I would love to come back as an alum and be a theatre professor here!”

But for now, he’s focused on this semester and that feeling of pride that will come on graduation day.

“When I walk on the stage at Commencement, I’m going to think of everything that’s happened, all this craziness, and the fact that I am a first-generation college student,” says Bryson, whose grandparents cosigned his first student loan, and who works at Dunkin’ Donuts to make ends meet. “I’ve gotten a lot of support from my family, telling me ‘You can do it, you got this.’”

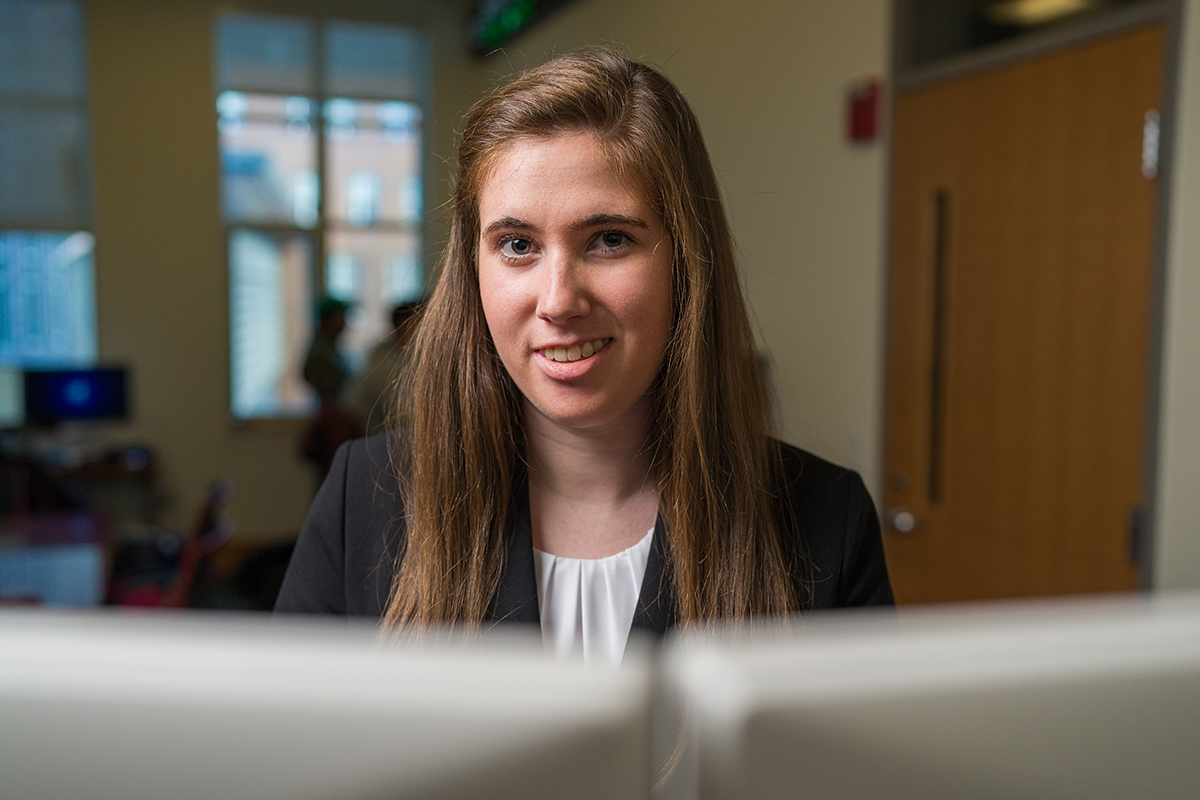

Sarah Blampied

tried to do a lot of self-reflection. There has been so much happening that we can’t control, I’ve just tried to control the small things you’re a part of.”

That’s how Sarah Blampied ’22 says she managed the stress of the last two years of college. As a finance and accounting major in Paul College, this year she is president of the Atkins Investment Group, a student-managed investment fund.

The group of sophomores, juniors and seniors from all colleges at UNH are provided with a unique opportunity to learn about active investing and portfolio management. Students benefit from the collaborative nature of the group and the guidance of experienced advisers, alumni and industry professionals.

She says current members and alumni of the Atkins group have been people she can lean on to navigate the last two years. “The whole group is student-run, so whether you graduated or not, we all stay connected, so in terms of jobs and internships, being able to reach out to those members who have probably worked with these same companies has been great.”

She’s also recipient of two prestigious scholarships from the Paul Scholars program and the Hamel Scholars program and is a member of the Hamel Scholars program food insecurity and homelessness task force, working with Waysmeet and other nonprofits on various community service projects.

A native of Bethlehem, New Hampshire, Blampied is one of many Wildcats in her family, including her grandparents and an aunt and uncle. She gave kudos to UNH for finding a way to keep the university operating as close to normal as possible, while keeping students safe. “I mean, five of my six junior year classes were in person, so it feels like UNH has been consistent, which I’m so happy about. I hear stories from other friends at different colleges and it has not gone smoothly,” she says.

She’s accepted a position in the financial leadership development program at Raytheon, a three-year leadership training program where participants rotate through different assignments such as accounting, internal audit, proposal development, and financial planning and analysis.

She says by focusing on her ambitions, and finding support from family and her Atkins peers, she’s been able to keep a “glass-half-full” mentality.

“Life is going to continue to change, so I’ve learned it’s important to always have an open mind and learn how to adapt to a situation,” she says.

Aubrey Porter

ubrey Porter is from the small town of Goshen, New Hampshire — small as in … wicked tiny.

“My graduating class from high school only had 28 people in it,” the psychology major says. So when UNH students got sent home mid-semester her sophomore year, it was tough. “It’s a small town so it felt super safe, but I was also super bored,” she admits.

At UNH, she’s much busier. The senior has been involved with Alpha Phi Omega, a community service co-ed fraternity; Psi Chi, the psychology honor society; the National Alliance of Mental Illness; and the Shadow a Wildcat program. She’s also been a peer mentor in the Honors Program. Since freshman year she’s volunteered at the Waysmeet Center’s weekly food pantries as well as its community dinners and drum circles. She’s been on the Waysmeet board of directors and was the food pantry coordinator, organizing and managing volunteers and helping patrons receive food. She got hooked on volunteering through UNH’s PrOVES pre-orientation program in the summer of 2018, where she volunteered at various local organizations such as the Seacoast Science Center and Strawbery Banke.

She laments the fact that the pandemic, once thought to be short-lived, has now become an everyday backdrop. “It just feels so long, and it’s affected so much. I wanted to study abroad, and now I’ll have to do that on my own time,” says Porter, who’s also a Spanish minor. “I wanted to go on Alternative Spring Break, but that trip was cancelled.”

Porter had worked as an undergraduate research assistant with assistant professor Robert S. Ross, performing neuroscience research, and is now working with kinesiology professor Ronald Croce, studying motor learning and brain activity. When not in a lab during warmer weather, she’s probably out on Spinney Lane at the Organic Gardening Club’s farm.

She could see herself as a therapist and may pursue her master’s in social work in the future but is currently working on earning a certified nonprofit professional credential, as she’s also interested in working in the nonprofit world. She says raising awareness around mental health challenges is one silver lining of the pandemic. “A positive way to look at it is that people feel more comfortable talking about struggling with mental health.”

For herself, Porter says maintaining her mental well-being has been the most challenging part of the past two years. “It was hard for me to focus in online classes,” and she found in the early days of the pandemic, she was stressing more about big assignments and essays. She found she had to tell herself that “good enough was good enough” and that assignments she turned in might not always be perfect.

She says the isolation of the pandemic has made her appreciate times she gets to spend in-person in classes, or with friends. “I did go to a lot of Zoom meetings for clubs, but it’s not the same kind of social interaction. It makes you realize how much in-person stuff matters, and how much we just took that for granted.”

Alex Carbone

or Alex Carbone, college during a global pandemic has meant being on the frontlines in hospitals, vaccination clinics and COVID testing sites, getting real-world experience toward his degree.

The nursing program at UNH was already a very practical and rigorous training for the next generation of nurses, but the pandemic and need for staffing thrust nursing majors like Carbone into the fight against COVID, answering the call for volunteers to staff different state and local vaccination and testing sites for the past several months.

“At one point, we were getting texts every single day about the need for nursing aides,” Carbone says.

The frontline experiences more than made up for the time when in-person clinical rotations (where a group of students rotate one day a week into a hospital or nursing setting with a clinical faculty member) were moved online for many of Carbone’s nursing peers during that first COVID spring of 2020. When students returned that fall, Carbone says it felt like a privilege to give a helping hand where they were needed, including helping on campus with testing through UNH Health and Wellness. In the spring of 2021, Carbone worked with a VNA nurse, and in the fall, worked at an elementary school assisting the school nurse.

“Most of the medical staff we work with are so happy to have us. Especially in that school setting, where it was one school nurse and 400 kids: She had so much administrative work and weekly surveillance testing, she was happy to have an extra set of hands,” Carbone says. “And the visiting nurse who would normally have five patients in a day was getting assigned nearly double that.”

Since his sophomore year, he’s also worked a part-time job as a nurse’s aide in the Emergency Department at Boston Children’s Hospital, picking up shifts whenever he could, spending as much as 40 hours a week there during J-term this year.

It was at Children’s that Carbone first saw the mental health crisis that so many only hear about in the news. He said with so few beds available for those seeking mental health treatment — and with mental health challenges spiking — emergency rooms have become holding areas for those in crisis while they await proper mental health care.

“There are patients who are boarding for weeks at a time — sometimes patients awaiting inpatient psychiatric treatment take up half the beds in the Emergency Department, waiting for a spot in a facility.”

The Exeter, New Hampshire, native has always wanted to go into a career in medicine and says while some ask why not the role of doctor or physician’s assistant, Carbone feels that nurses have a unique advantage over those types of careers.

“I have a couple of aunts who are nurses, and I was able to shadow one of them on a shift,” says Carbone. “That helped me make the decision; I prefer more interaction with patients than you get as a doctor. I like making connections with patients and having time to get to know them as I work with them.”

He knows the same confluence of factors that made more hands-on training available to nursing students is having an opposite, negative affect on working nurses, with many experiencing burnout amid staffing shortages and more patients in crisis. Nursing faculty at UNH have mentioned the phenomenon in classes, that students will be entering the nursing field in a time when veteran nurses who might have provided on-the-job advice and training might not be as accessible due to high turnover.

“I’ll admit it’s been a little bit discouraging to think about that trend,” Carbone says. “But I’m trying to keep a positive outlook on it. Maybe by the time we enter the workforce, things will be a little bit better.”

Carbone, who also works at the Hamel Rec Center, says the lessons of the pandemic have been the importance of flexibility and staying busy — too busy to dwell on the challenges of the last two years.

“We’ve had to approach this from a very open mindset; I think our nursing class of 2022 has really been rolling with the punches, and we’ve been able to step up and help out. Every part of the college experience has undergone some kind of adaptation,” he says. “But having had these experiences in frontline settings, having been through all that and still being excited to go into nursing, I know I chose the right job.”