Searching for Answers

But the 63-year-old mother and grandmother was never seen again. For more than four decades, her family never knew what happened to her. She wouldn’t have walked out on her life; her family recalled her being in good spirits that rainy July day. Was she the victim of a crime in this quiet northern New Hampshire town where she had grown up?

The questions lingered until, some 43 years later and 12 feet down into the Connecticut River, a UNH professor and her students were part of the team that finally solved the mystery and brought peace to Leeman’s family.

he Leeman case is just one of more than a dozen that the students in the Forensic Anthropology Identification and Recovery (FAIR) Lab at UNH have been working on under the guidance of forensic anthropology assistant professor Amy Michael.

The lab, operating out of the basement of Morrill Hall, is made up of roughly eight students each semester (two paid positions and five to six volunteers) who use real-world cold cases and long unidentified remains as coursework to learn more about this area of anthropology.

If you read “forensic” and immediately think of the wildly popular genre of true-crime TV shows and podcasts where amateur sleuths are hunting down serial killers and making headlines by solving famous crimes that have long stumped traditional law enforcement — you’re only partly right.

When UNH’s FAIR Lab works with law enforcement or the medical examiner’s office, it’s a win-win for students and the state: remains are identified and criminal investigations get closer to being solved, and students get hands-on, real-time experience not only in forensic anthropology, but in the investigative process of police and others working in criminal justice. (See sidebar for details on recent cases, below.)

“Dr. Michael is a wealth of knowledge to us,” says Sgt. Mallory Littman of the New Hampshire State Police’s Major Crimes Unit. “Not only are she and her students called out in the field during searches for remains, but she has made herself available to us to assist with learning about new forensic technologies.”

Law enforcement will call upon Michael and her students to take part in would-be criminal cases — recently being on site in a search for human remains in a missing child case, for example. The state medical examiner’s office, like most around the country, sometimes finds itself backlogged with unidentified remains, thanks to either chronic understaffing, the rise in death investigations due to the opioid crisis or a combination of both. So when Michael’s students step in to identify remains in those cases dubbed “historical” — where no crime is suspected, but human remains have been found and need to be identified — the state benefits and, in many cases, families can find closure. That was the result for the family of Alberta Leeman, whose death was determined to be the result of a motor vehicle accident.

“We are incrementally getting solves and clearing cases,” says Michael. “We work with state agencies in a highly collaborative way; we’ve inserted ourselves because we have the ability to connect the threads that are all there, and connect them into some meaningful resolution.”

Want to help solve a cold case?

Finding Her Passion

“I worked at Goodwill for $5.15 an hour, and I thought ‘this can’t be it,’” she recalls. She describes her first year at college as pretty aimless, until she took a course in biological anthropology, taught by University of Iowa professor Robert Franciscus. His lectures about what existed before modern human fossils were studied fascinated Michael.

“I learned there was this work so much older than what I’ve been told, and it was so much more complex and interesting when it comes to human culture, and even what came before human culture,” says Michael.

She wanted to know more. “For whatever reason, I marched up to him at the end of a class and asked if I could work in his lab,” she says.

It worked — she started working in his lab soon after.

She learned a valuable lesson from the experience, she says: that it’s not always intellect, but tenacity that gets you ahead. “I was super interested, I showed up at the lab and tried to make myself helpful however I could,” she says. “I know it sounds corny, but Dr. Franciscus seriously saved my life. That experience gave me self-esteem. I never felt smart before, but I learned that my curiosity was part of studying humans and learning, and that if I showed up, that was the key, straight up, into this very cool world.”

It’s a lesson she imparts on the students she works with at UNH, encouraging their curiosity and self-motivation as they work on cases.

Another part of what clicked for Michael was the satisfaction of solving mysteries, the more complex the better.

In her two classes last semester (Cold Cases and Introduction to Forensic Anthropology), Michael’s students learned the basics of identifying human remains, from learning search and recovery methods to related topics such as ethics in investigations, media bias, forensic genealogy, use of databases, critical thinking and forensics in true-crime media such as podcasts and TV shows, and understanding gender diversity in cold cases. Both courses featured numerous guest speakers from the criminal justice area, including New Hampshire Department of Justice investigator Fred Lulka and assistant medical examiner Dr. Mitchell Weinberg.

The students who go on from those classes to work in the FAIR Lab share Michael’s “deep intolerance for injustice,” she says, and so employ their skills to do what they can to remedy what she characterizes as a national epidemic of unidentified remains, especially among marginalized or Indigenous communities.

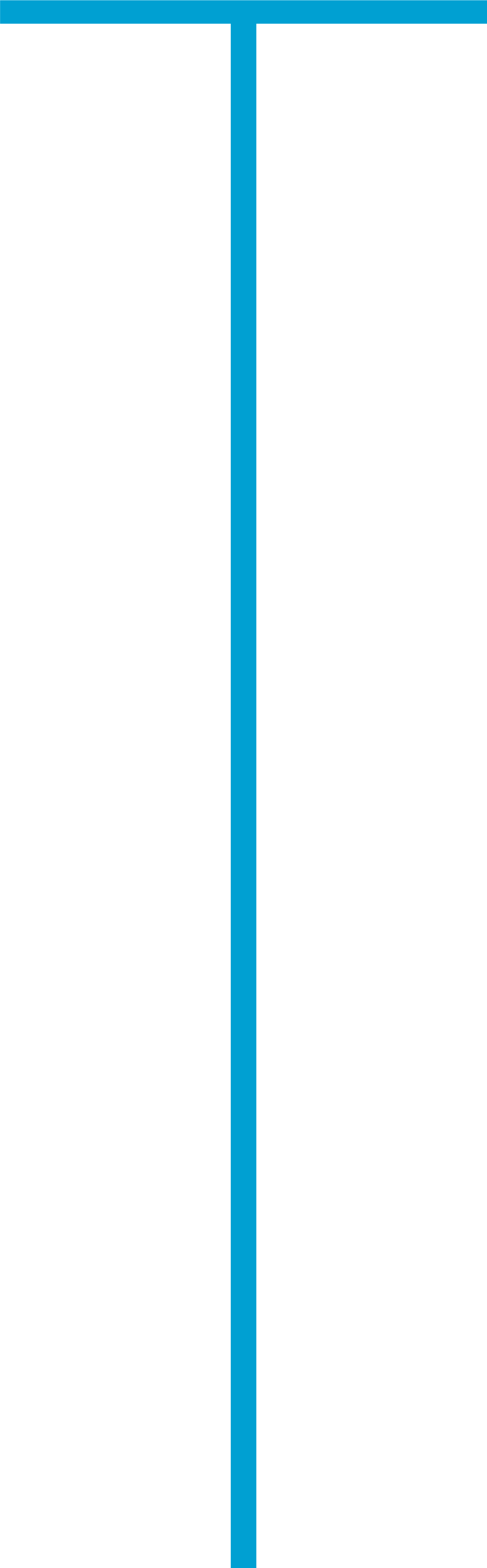

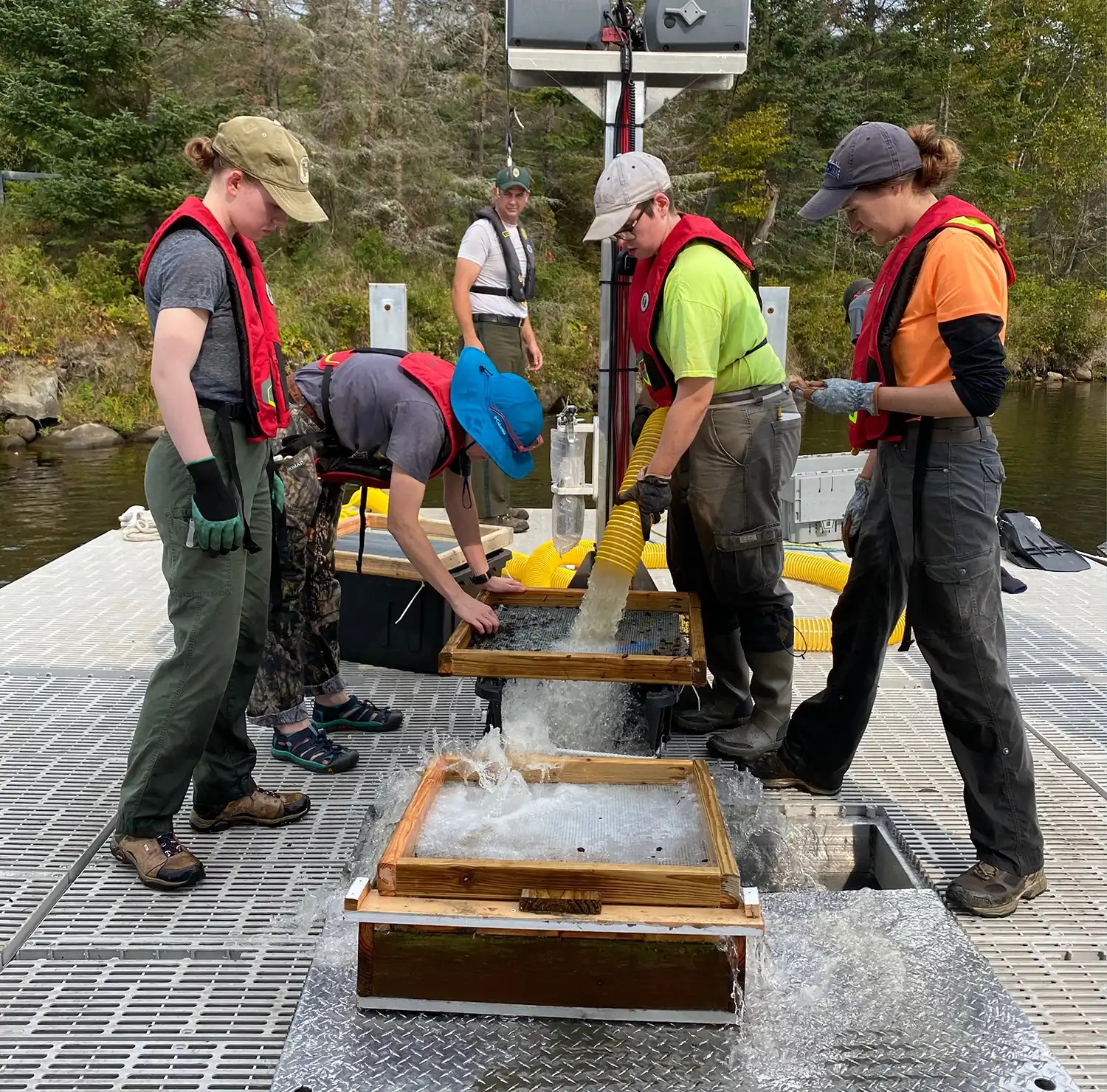

This illustration shows how the recovery system worked at the Alberta Leeman recovery site. The Venturi system was used by members of the anthropology and dive teams on the Dive Dock floating over the submerged vehicle and underwater.

Student experiences

Maronie became involved in the lab during his sophomore year, soon after he read a story about Kevin Cooper, a man on California’s death row whose case was reopened based on misdeeds suspected during the original investigation in 1983. The possible miscarriage of justice caught Maronie’s attention.

“I had an idea that the justice system was messed up: You can be actively made into the villain, even if you aren’t,” Maronie recalls. “The U.S. prides itself on its fair justice system, but if we’re allowing people to get swept under the rug and leaving them behind, how can we hold ourselves to that standard?”

That underlying theme of justice met with Maronie’s fascination with one of the main tenets of anthropology: “the idea that we can study was makes everyone them,” he says.

After taking Intro to Forensics with Michael, he changed his major to a self-designed program in forensic science.

So for the weeks he looked at the co-mingled bones, working to identify how many lives they represent and what happened to them before their death, he did so believing he’s performing an act of justice.

He’s determined, through months of research and working with a local historical society, that the remains likely came from what was a burial area on a poor farm, common in New England in the 1800s and early 1900s, where homeless or indigent people would work for brief stints to pick up wages.

Despite the fact that he might not be able to identify the names of each of the remains, “does that mean they don’t deserve to be properly buried somewhere? It’s a matter of justice after the fact vs. prior” and using forensic anthropology to correct wrongs of the past, he says. “I know people make mistakes, but we also have the capability to go back and say, ‘OK this was wrong and we have to fix it.’”

Based on his work, Maronie will attend a reburial ceremony at the Brentwood Town Cemetery this spring.

He plans to pursue advanced degrees in the field, and hopes to one day work for the Innocence Project, which works to free innocent people who have been wrongly convicted and advocates for justice system reform to prevent wrongful convictions.

For students, forensic anthropology work requires not only investigative curiosity and technical skill, but also a talent for research and culling together sources to create a complete picture. It also requires a social sensitivity — remembering that each set of skeletal remains is someone’s family member or friend, that they lived a life that was of value and that they are more than just a mystery to solve.

The process starts with archival research, searching through digitized newspapers from the area where remains were discovered, gathering any information from law enforcement, combing through public databases on sites like ancestry.com, even researching town maps, as land-use records might reveal long-forgotten cemeteries that would explain human remains being found in a location. At the same time, skeletal analysis is being done to start to identify ethnic background, gender, any obvious trauma, dental attributes and other physical cues.

From there, traditional research and bone study meet modern-day online media research, especially in the area of social media. “Sometimes we’ll be combing through comments on Reddit or Facebook,” says Kylee Jedraszek ’23, who works in the FAIR Lab. It’s also a bit of legwork: Jedraszek’s taken samples to dentists to get X-rays done and, like Maronie, spends time reaching out to historical societies, state archaeologists, medical examiners and state police when needed.

Michael and the FAIR Lab students also work closely with the DNA Doe Project, a nonprofit organization that uses investigative genetic genealogy to identify unidentified remains.

Jedraszek, who is pursuing an internship with the state police’s major crimes unit, sees the justice of forensic anthropology as doing right by that person’s loved ones.

“I really love what I’m doing because it’s a special thing to have the opportunity to make that difference in a family’s life,” she says.

Making Headlines

Alberta Leeman, missing since 1978: Amy Michael, Kyana Burgess ‘22, Alyssa Moreau ‘22, and Ry Friese ‘20 went out with N.H. Fish and Game search and rescue teams to recover the remains of who would turn out to be Alberta Leeman of Gorham, who had gone missing in 1978. The UNH team created the screening system, screened remains as they were pulled up to a dive dock using a Venturi system (essentially a fluid-extraction vacuum) and cataloged them. The identity of Leeman was eventually found through DNA testing from the remains that the UNH team was key to recovering.

Det. Christopher Elphick of the state police’s Cold Case Unit first worked with Michael on the Leeman case in 2021, and he credits her with pioneering the method to retrieve the remains from the submerged car. “We rely heavily on Amy’s expertise and resources; both Amy and her students have devoted a tremendous amount of time to many of our cases.”

Joseph Henry Loveless, an 1870s outlaw: Working with colleagues at Idaho State University, the Clark County Sheriff’s Office and the DNA Doe Project, Michael was part of the team that identified a man found in an Idaho cave in 1979 as Joseph Henry Loveless. An outlaw, Loveless was born in 1870 in Utah Territory and likely murdered more than a century ago. It’s one of the oldest identities ever recorded using genetic genealogy in a forensic case.

“These bones had been studied by anthropologists at the Smithsonian and the FBI and still remained unidentified, so the idea was to let genealogists have a run at it,” Michael says.

“Ina” Jane Doe, unidentified since 1993: Amy Michael had been familiar with the “Ina” Jane Doe case as a gruesome tale from her childhood in southern Illinois: a woman’s head was discovered by two children in a public park there in 1993.

In 2021, Michael reached out to the local sheriff’s office, offering to reexamine the case using updated methods, in partnership with Laurah Norton, writer and host of The Fall Line podcast, and Redgrave Research Forensic Service. Thanks to the group’s research over about 12 months, a year later, Michael and UNH students were invited to the press conference announcing the woman’s identity: Susan Lund, 25, of Tennessee. The criminal investigation into her death was quickly reopened by Illinois law enforcement.

Above: Ashanti Maronie ’23 studies the remains that his work has determined likely came from a poor farm in southern New Hampshire. The remains date back to the 1800s to early 1920s.

Left: While there are specialized tools for forensic anthropology work, household items such as toothbrushes are also commonly used.

Burgess says those lessons hit home in the case of “Ina” Jane Doe — a woman whose remains had been found in an Illinois park in 1993, but whose identity had remained a mystery. Working with a team of DNA testing agencies, genealogists and law enforcement, Michael and her students’ work ultimately helped lead to the remains being identified as Susan Lund, a 25-year-old woman from Tennessee.

“We were part of the press conference [where her identity was announced], and I got to meet her family there; I’d never met a victim’s family before,” Burgess explains. “It was a tough time for the families, but it was also a really powerful moment to think that even in those circumstances, while terrible, we can help bring that closure.”

Left to right: Kyana Burgess ’22, Dr. Les Fitzpatrick of UNH Anthropology Department, Ry Friese ’20, Alyssa Moreau ’21 take part in last year’s recovery work in the Alberta Leeman case.

Both Burgess and fellow alum Michaela Morrill ’21 work on The Fall Line, a true-crime podcast, in research and content creation, and Morrill has continued to work with Michael in the FAIR Lab.

“[My UNH experience] has helped me so much in respecting cultures and histories of people. Doing this kind of research on a set of remains is really such an intimate moment that we’re not always afforded, so we always respect that.”

Michael believes that the modern advances in forensic anthropology and in genetic genealogy mean that with proper funding, remains have a good chance of being identified.

“It seems unfair, with these advanced techniques we have now, that someone’s bones would sit on a shelf. Especially if we have DNA, it’s no longer an impossibility that we will identify you,” she says. “I have learned that so much of the things that happen in a life are related to what kind of family ties you have, what support you have, what resources you have. When those connections are frayed, and people seem to drop out of society, they shouldn’t be forgotten,” she says.

“People are so much more than the worst thing that happened to them.”