t the age most of her peers were just beginning college — 18 — Ana Gobledale ’75G arrived at UNH from Illinois to earn a Master of Arts in teaching. As a bored 14-year-old, she and a friend had acted upon her father’s teasing suggestion that they entertain themselves one summer Saturday by taking the CLEP college placement exam, and she ended up earning 24 credit hours toward college. Gobledale could claim those hours only if she enrolled in at least one college-level course, however, so as a high school sophomore, she took an evening intro to philosophy course at Central YMCA College in downtown Chicago, where her father taught. That class led to others, and the following year she left high school for Shimer College in Mt. Carroll, Illinois. A study abroad program, a stint traveling through Europe, and a transfer to Western Illinois University later, she had an undergraduate degree in English in hand — and a plan to eventually teach at the college level.

“I was the young kid on the block, for sure, and hardly older than the students in our summer ‘Live, Learn and Teach’ program,” Gobledale recalls of her time at UNH. “I’m grateful to the professor who put my age aside and expected as much of me as the others in the program.”

Gobledale left Durham 15 months later with a graduate teaching degree and a solid foundation in pedagogy that she took to her next adventure: a divinity degree from the University of Chicago. She subsequently met her husband, Tod, a fellow ordained Christian minister who had spent two years in the Peace Corps in Senegal, West Africa, and from 1984-1991 the couple served the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa. Living illegally as white foreigners in a Zulu community during apartheid, Gobledale and her family, which expanded to include children Thandiwe and Mandlenkosi, undertook perhaps the most important educational process of all: lessons in living.

“‘We’ll put you and the baby in the storage closet.” Luckily there’s a window with a view of Durban’s rooftops and the Indian Ocean, and room for my bed. Following the Caesarean birth of my daughter, Thandiwe (“Beloved” in Zulu), the staff of McCord Zulu Hospital care for me in the closet for five days. Why am I in a closet? The “Missionary Room,” available for white people, already has an occupant, and, because of the laws of apartheid, I am not allowed a bed in the Black wards.

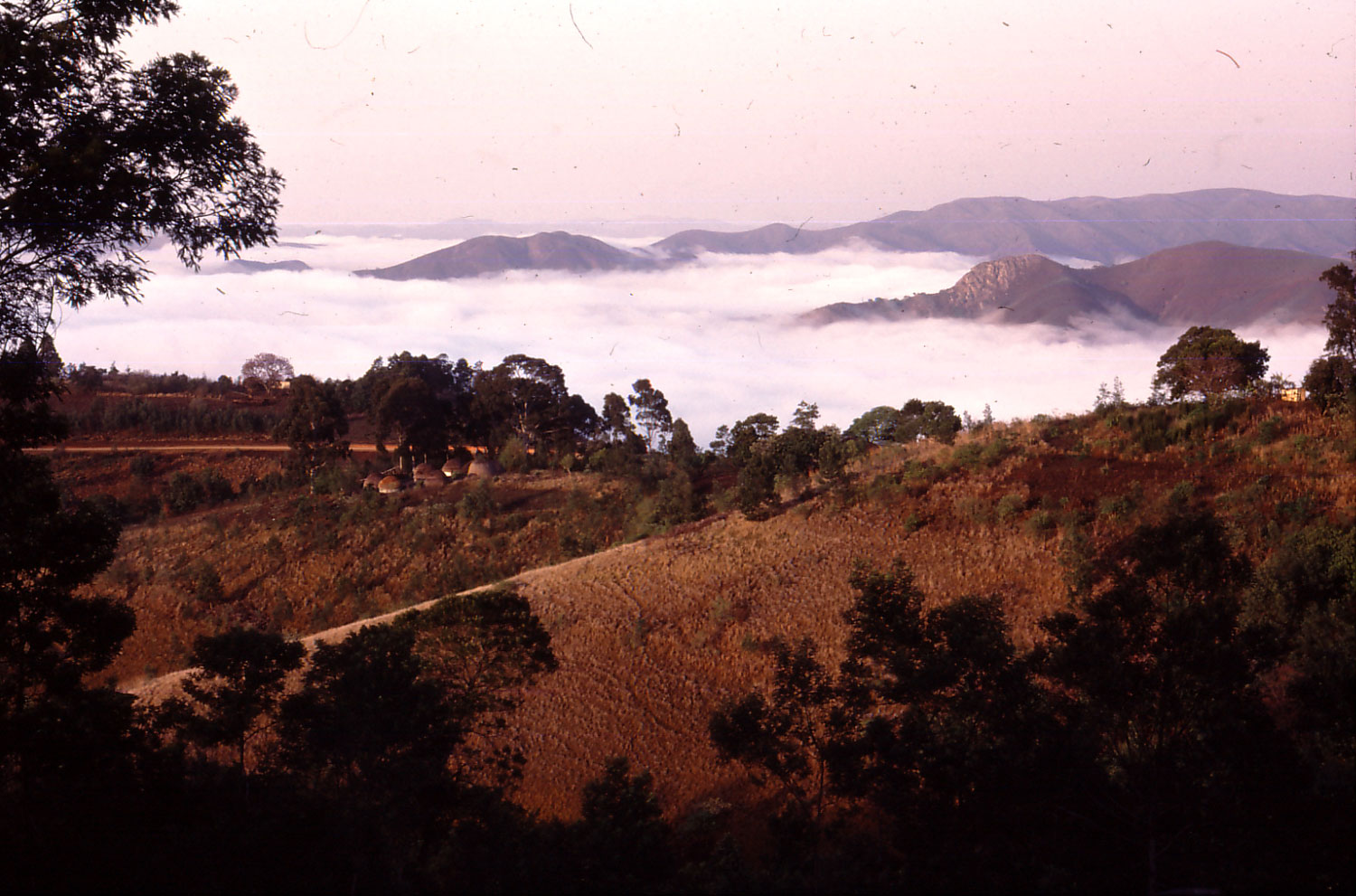

“I can’t build you a white toilet out here.” Tod and I visit the parsonage we’ll be moving into soon. There’s no toilet. This is rural South Africa — a place called Mfanefile in northern Zululand, later to be renamed KwaZulu Natal. The church is supporting our decision to live illegally in the Black homeland — no whites allowed. Our neighbor thinks we want a flush toilet (a “white” toilet), but we assure him we’re looking for a pit toilet, just like his, just like those of all our neighbors. The hole gets dug, and when the door to the house is open the spectacular view of Zululand hills stretches out before me. The land has never been claimed by whites as the slopes are steep and ground undesirable for farming or ranching. This is our home for almost five years — some of my happiest.

“No one can live like that.” We learn the racism and hatred of many South African whites firsthand. We are grateful for the church, which persists in presenting a multi-racial and multi-cultural reality that defies a societal status quo that insists different races cannot live, work and learn together. Many church leaders and members are imprisoned, considered “threats” during the apartheid clampdown. Finally, two members of the Special Branch visit our rural home and present us with a two-week notice to leave South Africa. The church intervenes and negotiates a six-month extension. When our departure date arrives, sadness surrounds us as we bid farewell to the one home our children have known.

After leaving South Africa, Gobledale and her family spent three years in Franklin, New Hampshire, then returned to Africa, this time to Zimbabwe for five years, followed by five years in Australia and a decade in the United Kingdom, where they will soon become citizens. Each culture, she says, has offered lessons on justice and injustice, equality and racism, welcome and xenophobia, respect and homophobia, the idea of the common good and the destructive consequences of individual entitlement. “Living in southern Africa, especially, opened my eyes to the depths of racism but also to the vibrant hope, held by many, of ‘a new heaven and a new Earth,’” she says.

Some 45 years later, she’s grateful for the role UNH played in her global education. “UNH opened my mind to creative, engaging and worthwhile learning experiences, both as a teacher and as a learner,” she says. “I’ve never looked back.”