Dinesh Thakur ’92G

Erica Tamposi ’14

Gov. Stephen Merrill ’69

Robert Coffey ’05G

arly in this year’s State of the University address, my annual report to the Wildcat community, l talked about how proud I am of UNH’s response to COVID-19: How hundreds of faculty and staff rallied to transition our classes online last spring, along with most of our research. How they then worked long hours over the summer preparing our campuses to reopen in the fall with in-person learning and created a comprehensive public health campaign to keep our community safe and operational. How they built and staffed two state-of-the-art COVID testing labs on our Durham campus, and one on our Manchester campus, which have now handled more than 350,000 tests. Today, our COVID testing program is among the finest, most effective in U.S. higher education.

I noted, too, that more than 400,000 Americans (now over 500,000), including more than 1,000 here in New Hampshire, were among the 2 million individuals globally who had lost their lives in the pandemic. Their numbers include friends and family from our UNH community. “Our hearts go out to each of you who lost a loved one,” I said, and paused.

In that fleeting silence, the weight of it all hit home. History will show that 2020 was a year of unprecedented challenges and real pain. But I believe it also will show that our response reflected the compassion, resiliency, creativity and pride that define our Wildcat family.

Kristin Waterfield Duisberg

Current Editor

Jody Record ’95

Class Notes Editor

Allison Battles ’02

Feature Writers

Bethany Clarke ’20G

Michelle Morrissey ’97

Keith Testa

Contributing and Staff Writers

Allison Battles ’02

Callie Carr

Ali Goldstein

Brooks Payette ’12

Robbin Ray ’82

Jody Record ’95

Keith Testa

Contributing and Staff Photographers

John Bazemore/AP

Justin Britton

Jonathan Fanning

Jeremy Gasowski

Jure Makovec/Getty Images

Lisa Nugent

Beth Potier

Scott Ripley

Marto Tacca/AP

Matt Troisi ’22

David Vogt

China Wong ’18

◆

Editorial Office

15 Strafford Ave., Durham, NH 03824

alumni.editor@unh.edu

Publication Board of Directors

James W. Dean Jr.

President, University of New Hampshire

Debbie Dutton

Vice President, Advancement

Mica Stark ’96

Associate Vice President,

Communications and Public Affairs

Susan Entz ’08G

Associate Vice President, Alumni Association

Heidi Dufour Ames ’02

President, UNH Alumni Association

◆

◆

UNH Magazine is published three times a year by the University of New Hampshire, Office of University Communications and Public Affairs and the Office of the President.

© 2021, University of New Hampshire. Readers may send letters, news items and email address changes to alumni.editor@unh.edu.

s this issue of UNH Magazine goes live, UNH is closing in on a remarkable milestone: one full year of remote operations. If someone had told me on March 16, 2020, as I prepared to work from home for a few weeks — gathering up a few extra story files for the spring/summer magazine and a handful of books I wanted to consider for “Bookshelf” — that one year later I’d be fully moved into a home office with three complete online-only issues of the magazine under my belt, I would have told them their crystal ball must surely be broken. At the time, a month or two of remote work sounded like a welcome change of pace. But a whole year? Impossible.

“I became a civil engineer because my parents worked in construction. I was an excellent student in math and science, so engineering seemed like a reasonable option,” she says. “I expected to receive my degree and work. I had no idea that I would spend my career in higher education. In fact, I had no idea that was even an option.”

It is a position for which Sullivan is eminently qualified. He previously served in former President Barack Obama’s administration as deputy assistant to the president, helped to negotiate the Iran nuclear deal and was national security advisor to then Vice President Biden. He was deputy chief of staff to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and a senior policy advisor during her run for president in 2016.

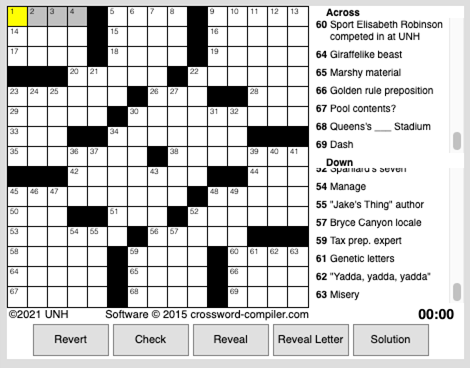

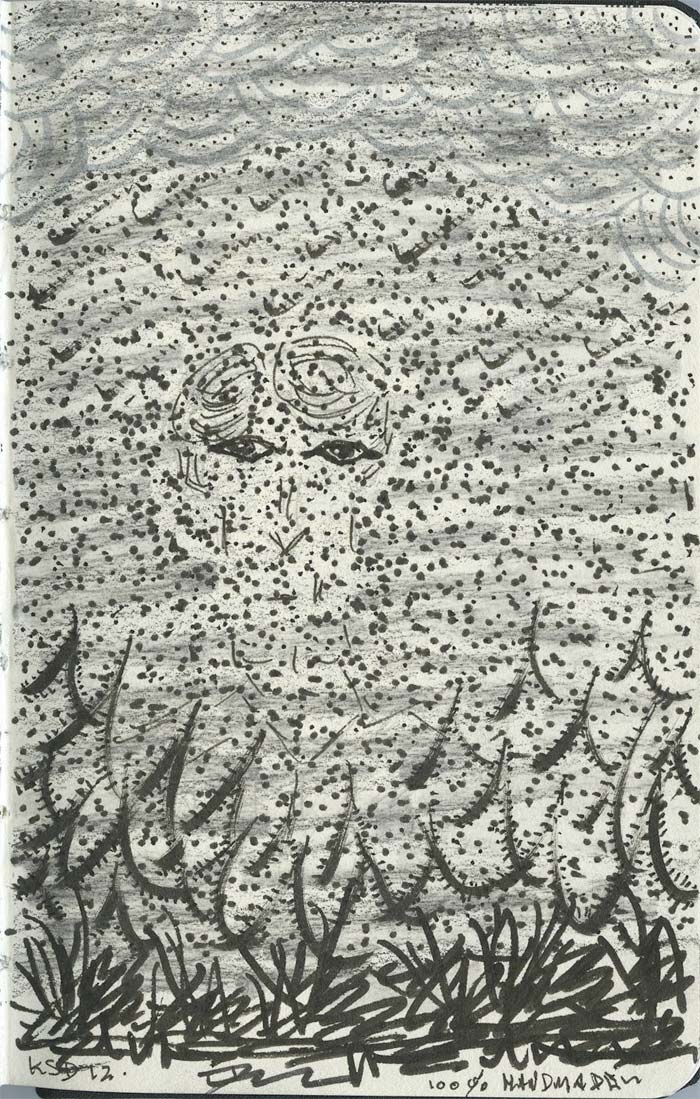

t’s not as if Dana Jennings ’80 couldn’t find the words. An editor for the New York Times, Jennings started out as a print journalist. He’s written three novels, two works of nonfiction and a children’s book. #hecanwrite.

But to talk about the impact a literal toxic environment had on his life, to make the audience understand the smells and sounds and the poison that spewed from the 55-gallon steel drums at Kingston Steel Drum, Jennings picked up a different pen. And he sketched. Furiously, it seems to the eye. Purposely. Telling the story of his father’s cancer, his own cancer and the rage against the hazardous waste site where both worked decades earlier.

Even with campus quiet for an extended period of time during the COVID-lengthened semester break, there was a close-knit crew of students and staff caring for the university’s herds. Like animal science senior Hannah Majewski ’21, who grew up participating in 4-H and started working with the campus cows her sophomore year. She’s one of four student workers who live above the Fairchild Dairy Teaching and Research Center, in apartments the students simply refer to as “upstairs.”

Every morning, Majewski is up at 3:30 to milk and care for the cows. Alongside her regular chores — from cleaning stalls to providing fresh grain — she’s also sure to give the cows some pampering, like scratches behind the ears.

Even with campus quiet for an extended period of time during the COVID-lengthened semester break, there was a close-knit crew of students and staff caring for the university’s herds. Like animal science senior Hannah Majewski ’21, who grew up participating in 4-H and started working with the campus cows her sophomore year. She’s one of four student workers who live above the Fairchild Dairy Teaching and Research Center, in apartments the students simply refer to as “upstairs.”

Every morning, Majewski is up at 3:30 to milk and care for the cows. Alongside her regular chores — from cleaning stalls to providing fresh grain — she’s also sure to give the cows some pampering, like scratches behind the ears.

he university’s Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program recently received the MacArthur Award as the No.1 top-performing unit out of 42 units in the brigade, which includes New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and New England. The unit learned of the award via a videoconference in January.

The annual award is given based on academic and fitness scores, retention and commissioning rates, program administrative metrics and organizational culture. It has been presented annually since 1989 by the U.S. Army Cadet Command and the Gen. Douglas MacArthur Foundation to recognize the ideals of duty, honor and country.

he university’s Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program recently received the MacArthur Award as the No.1 top-performing unit out of 42 units in the brigade, which includes New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and New England. The unit learned of the award via a videoconference in January.

The annual award is given based on academic and fitness scores, retention and commissioning rates, program administrative metrics and organizational culture. It has been presented annually since 1989 by the U.S. Army Cadet Command and the Gen. Douglas MacArthur Foundation to recognize the ideals of duty, honor and country.

ancer research has come a long way, but there are many miles to go, particularly for forms of the disease for which there is currently no known cure. Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), a rare form of lymphoma, is one of those cancers — today, there is only one FDA-approved treatment. But with the work being done at UNH, that may one day change.

Researchers have taken the novel approach of targeting specific cell proteins that control DNA information using inhibitors, a class of immunotherapy drugs that are known to be effective in reducing the growth of cancer cells. What’s more, when combined with a second drug, these inhibitors were even more successful in killing the WM cancer cells — a finding which could lead to more treatment options in the future.

hen it comes to spring sports, one’s thoughts typically turn to baseball. The crack of the bat echoing in the crisp air. The clap of the ball against a worn leather mitt. But at UNH in 2021, spring means football.

As with so many things during COVID-19, the virus prevented the Wildcats from taking the field in the fall when all UNH sports were postponed. Almost immediately, there was talk of moving the football season to spring, but it wasn’t official until the Colonial Athletic Association (CAA) unveiled its spring schedule Oct. 27.

It was certainly more than welcome news for the Wildcats. UNH began its season at home vs. Albany on March 5.

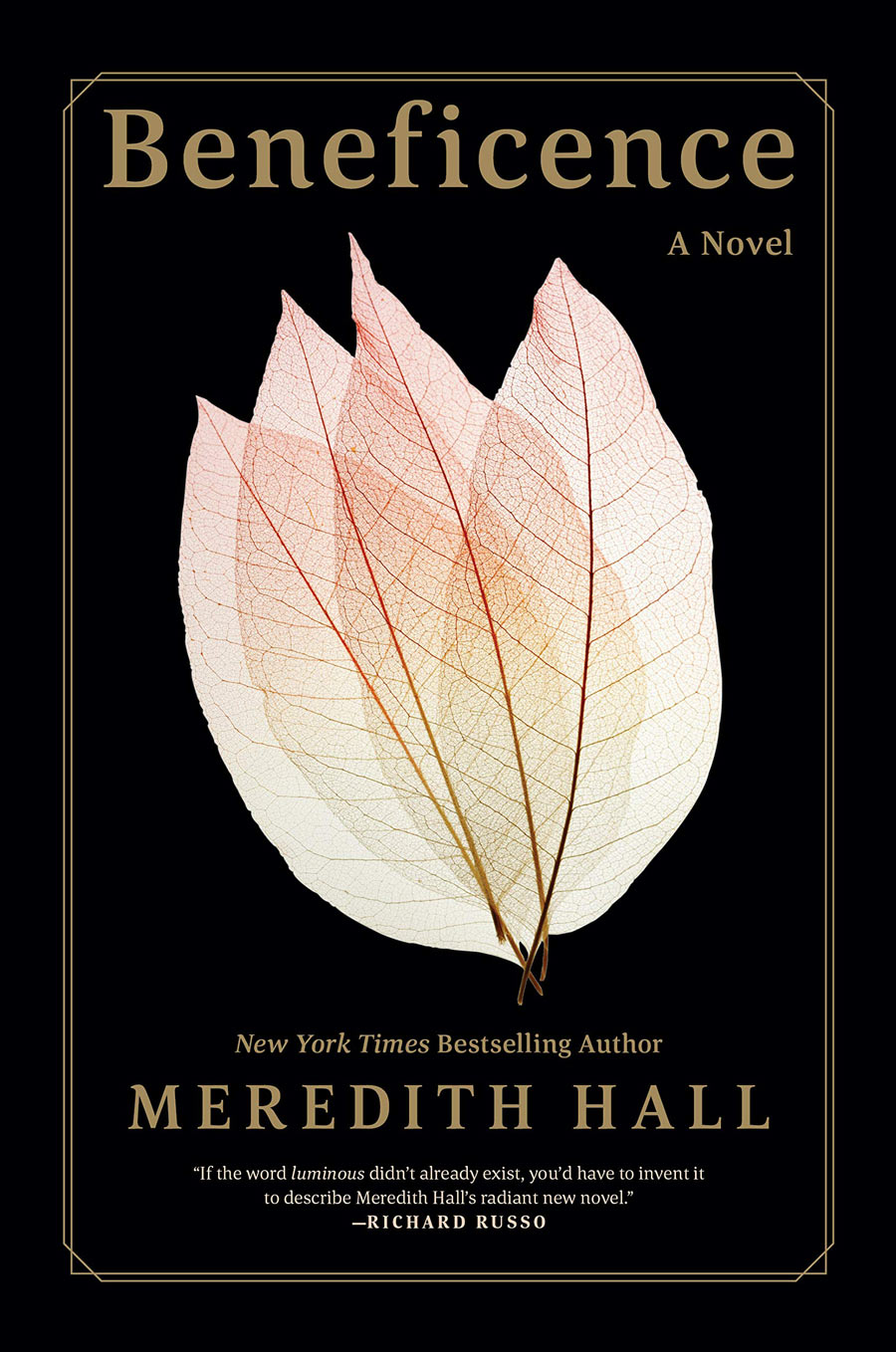

David R. Godine,

Oct. 2020

n fictional Alstead, Maine, the Senter family — parents Tup and Doris and children Sonny, Dodie and Beston — live off the 236 acres of good land that’s been in Tup’s family for generations, and in which Tup’s forbearers are buried. In alternating chapters, Doris, Tup and Dodie take turns describing a quiet, steady life of hard work and deep contentment as they run their dairy farm. But it doesn’t take long for Doris to make an assertion that presages a tragedy that will turn the family of five to a family of four: “I have learned that nothing terrible is going to happen here. You have to be careful, to pay attention, and then you just trust that everything is going to be all right. It’s a price you pay for the quiet and beauty of the land.”

Nature

raising greatness

Nature

lessons while

raising greatness

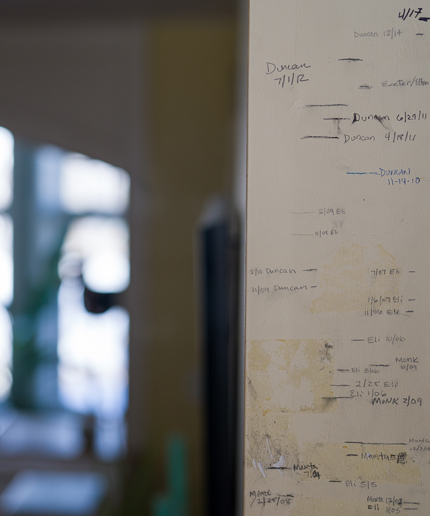

ife as a professional basketball player can be a nomadic adventure. Few are as well-acquainted with that experience as New Hampshire native Duncan Robinson, whose circuitous path to the NBA once included a winter stretch shuttling back-and-forth between the conflicting climates of South Dakota and South Beach.

Robinson has since established himself as a starter on a Miami Heat team that went to the NBA Finals last season, but he still faces the mental and physical grind of living out of a suitcase for days or weeks at a time, bouncing from city to city on overnight flights and maintaining a schedule on which stability and regularity are in short supply.

As physicians, our weapons lie beyond medications, diagnostic tools and interventions. Our weapons include our composure, our compassion and our competence. Where there is panic, we provide calm. Where there is fear, we offer courage. And where there is anger, we practice patience. We continue to stand united as a medical community despite having to stand six feet apart.

hen her son Jim Scott III was 23, Janet Scott was told she should find a nursing home for him to live out the rest of his life. It was 2006, and Jim had been seriously injured in a car accident. He was suffering from a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and a host of other medical issues.

But putting her son in a nursing home would have felt like giving up, like failure — things that just aren’t in the Scott family DNA.

And 15 years later, the Scotts are using their philanthropy to help ensure that other people going through a similar medical crisis have options, as well. Janet and husband, Jim Scott Jr., own and operate RAWZ Natural Pet Food, a company they built with two goals: to make quality pet food and to donate 100% of its profits back to organizations that helped them navigate some of their family’s most challenging moments.

en Cariens’ office is lined with a row of sculpted heads. What looks like long tendrils of white string or spaghetti come from their open mouths. The effect is striking, as if the heads emerge from the walls surrounding them. It feels like they have something to say … or scream.

And indeed, the heads have a story to tell. For years, Cariens, an associate professor of art and art history at UNH since 2000, had the rubber mold for one of them laying around. Then, a vessel that was important to him broke — an antique vase from Korea. He glued it back together, and in the process realized there was something really meaningful about putting something back together. He was going through a divorce, reorganizing and grieving, so mending the vessel reminded him of mending himself. Soon after this, he rediscovered the rubber mold. He made a new cast with it, which he subsequently broke and repaired, a process of destruction and revival that evoked the Japanese art of kintsugi, which celebrates the “scars” of mended objects rather than treating them as something to be disguised. It was therapeutic.

“In the course of life, things break, and we have to put them back together,” Cariens says. “We have to put ourselves back together but there’s a real beauty in that process.”

en Cariens’ office is lined with a row of sculpted heads. What looks like long tendrils of white string or spaghetti come from their open mouths. The effect is striking, as if the heads emerge from the walls surrounding them. It feels like they have something to say … or scream.

And indeed, the heads have a story to tell. For years, Cariens, an associate professor of art and art history at UNH since 2000, had the rubber mold for one of them laying around. Then, a vessel that was important to him broke — an antique vase from Korea. He glued it back together, and in the process realized there was something really meaningful about putting something back together. He was going through a divorce, reorganizing and grieving, so mending the vessel reminded him of mending himself. Soon after this, he rediscovered the rubber mold. He made a new cast with it, which he subsequently broke and repaired, a process of destruction and revival that evoked the Japanese art of kintsugi, which celebrates the “scars” of mended objects rather than treating them as something to be disguised. It was therapeutic.

“In the course of life, things break, and we have to put them back together,” Cariens says. “We have to put ourselves back together but there’s a real beauty in that process.”

9 Rickey Drive

Maynard, MA 01754

bryantnab@yahoo.com; 978-501-0334

t the age most of her peers were just beginning college — 18 — Ana Gobledale ’75G arrived at UNH from Illinois to earn a Master of Arts in teaching. As a bored 14-year-old, she and a friend had acted upon her father’s teasing suggestion that they entertain themselves one summer Saturday by taking the CLEP college placement exam, and she ended up earning 24 credit hours toward college. Gobledale could claim those hours only if she enrolled in at least one college-level course, however, so as a high school sophomore, she took an evening intro to philosophy course at Central YMCA College in downtown Chicago, where her father taught. That class led to others, and the following year she left high school for Shimer College in Mt. Carroll, Illinois. A study abroad program, a stint traveling through Europe, and a transfer to Western Illinois University later, she had an undergraduate degree in English in hand — and a plan to eventually teach at the college level.

n summer 2003, Dinesh Thakur ’92G had been in his new job as director and global head of research information and portfolio management for Ranbaxy Laboratory in Guragon, India, for only a couple of months when he spotted a man, drunk and injured, laying in the middle of a busy road. Though he was on his way home from a long day at work, and though his driver urged him not to, Thakur insisted on stopping to carry the man off the road and transporting him to the nearest hospital, where his concern — and his willingness to pay for the injured man’s care, in cash, in advance of treatment — was met with suspicion. Indeed, the day after the incident, local police showed up at Thakur’s Ranbaxy office, assuming the only reason he’d helped the stranger had to be because he’d been the one who had run him over.

little more than three years ago, Erica Tamposi ’14 found herself in the enviable position of weighing job offers from Netflix — for production work similar to what she’d been doing for years — and the NFL Network. She ultimately chose the latter, citing the creative freedom that came with the position as the tiebreaker.

So, how’s that going?

When the NFL handed out its year-end awards at a glitzy gala the night before the Super Bowl a few years ago, Tamposi handed out wedding cakes, cellos and rolls of toilet paper as inconvenient gag gifts to unsuspecting red carpet recipients.

As photographers often say, the best camera is the one you have with you. For longtime UNH staffer and frequent UNH Magazine contributor Beth Potier, manager of research communications in Communications and Public Affairs and Office of the Senior Vice Provost for Research, Economic Engagement and Outreach, that happened to be her iPhone. She caught this shot on Durham’s Main Street on a February Friday morning as she waited for a group of fellow early risers to join her for a sunrise walk. “It was about 6:45, and the sun rising over the hill behind the Durham Community Church was just incredible,” Potier recalls. “Luckily, at that hour, I was able to stand in the middle of Main Street and just snap away.”

Potier shared the image on Twitter and it was subsequently picked up for UNH’s official Instagram page, where it racked up more than 7,400 likes in three days — and sparked some fun engagement with alumni, community members and at least one prospective grad student.