Frontlines

en Kruger ’03 can flip through memories from his time on the UNH campus like he’s thumbing through crates of used records, pausing for just a second to revel in each one before moving effortlessly to the next.

He spent one of his undergraduate years as student body president, relishing his time as a leader among his classmates and interacting with university administrators. He completed the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program, taking the first steps toward a fulfilling career in the New Hampshire National Guard, where he has achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel. He fondly recalls days and evenings spent hanging out in the Memorial Union Building (MUB), which he refers to as “the nexus” of social activity on campus.

But Kruger’s mental archives don’t end at graduation — in fact, if anything, the scenes he’s added since he earned his degree are even more vivid.

Frontlines

en Kruger ’03 can flip through memories from his time on the UNH campus like he’s thumbing through crates of used records, pausing for just a second to revel in each one before moving effortlessly to the next.

He spent one of his undergraduate years as student body president, relishing his time as a leader among his classmates and interacting with university administrators. He completed the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program, taking the first steps toward a fulfilling career in the New Hampshire National Guard, where he has achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel. He fondly recalls days and evenings spent hanging out in the Memorial Union Building (MUB), which he refers to as “the nexus” of social activity on campus.

But Kruger’s mental archives don’t end at graduation — in fact, if anything, the scenes he’s added since he earned his degree are even more vivid.

It’s safe to say “turning the site of my college fitness center into a makeshift hospital during a global pandemic” wasn’t on the list of memories Kruger anticipated making at UNH.

But that doesn’t make it any less gratifying.

“All the stops were pulled out by UNH to make this happen, and the National Guard was there to facilitate and provide direction. It was definitely a source of pride,” Kruger says. “It was inspirational to see that as a community, we can be stronger than COVID-19. The attitude of the university was, even if this helps save one person, it’s worth it.”

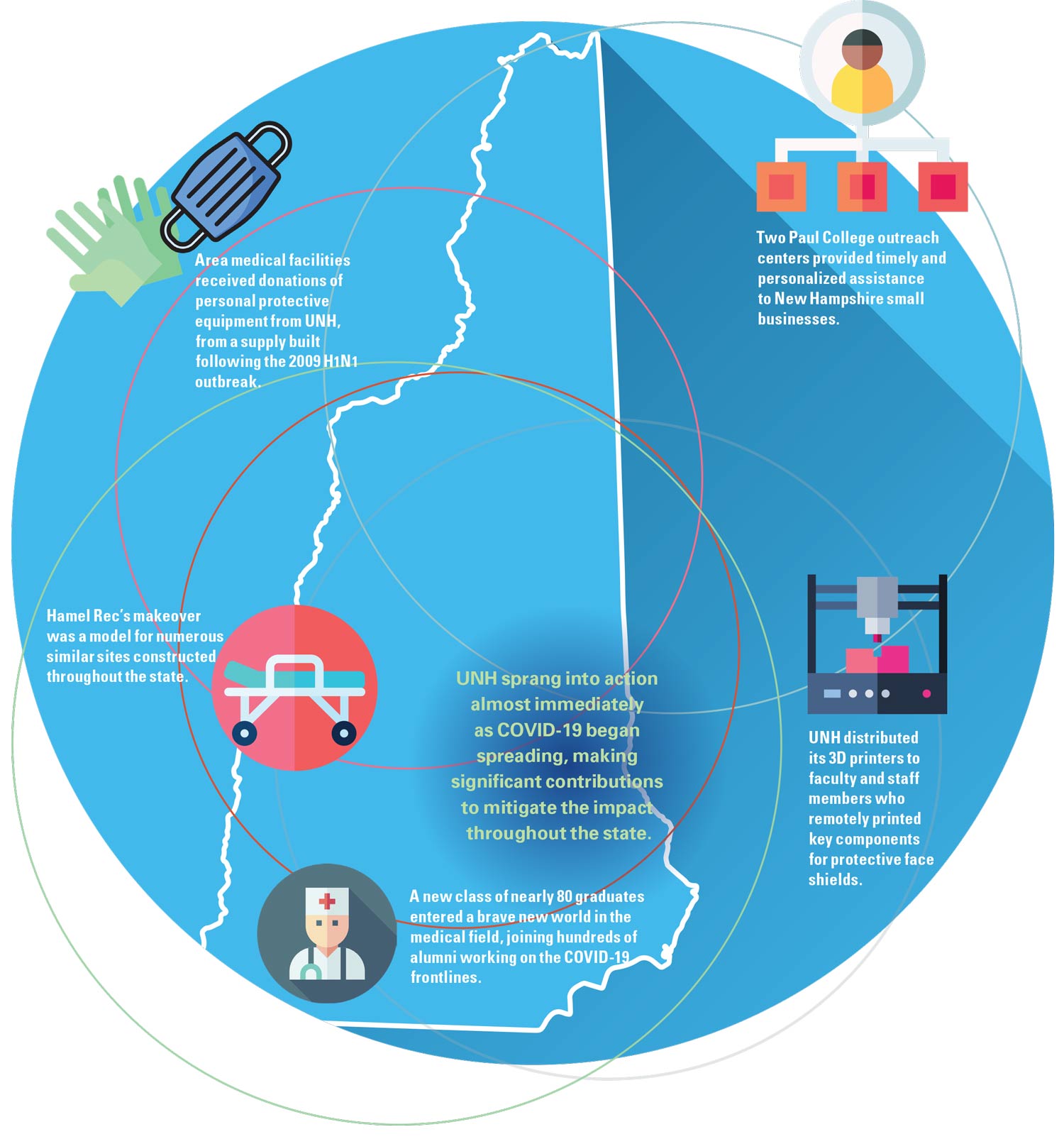

That attitude is what fueled the university to spring into action almost immediately as COVID-19 began spreading, prompting significant contributions to mitigate the impact throughout the state.

There was the aforementioned Hamel Rec makeover, which proved to be something of a model for numerous similar sites constructed throughout New Hampshire at the request of Gov. Chris Sununu and the State Department of Health and Human Services. There was the sizeable donation of personal protective equipment (PPE) to local caregivers at multiple medical facilities, and the widespread use of university 3D printers to create key components used in protective face shields. There was timely and personalized assistance provided to New Hampshire businesses by two Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics outreach centers. There was a new class of nearly 80 nursing graduates entering a brave new world in the medical field, joining hundreds of previous alumni, some of whom have been active on the COVID-19 frontlines.

Even as UNH undertook the daunting task of shifting all coursework and professor-student interaction to a fully online format, helping protect the state and provide as many resources as possible to those in need was not only a focus, but a priority.

“Everyone at the university takes tremendous pride in being New Hampshire’s flagship institution, and that comes with a sense of responsibility to give back when the opportunity presents itself,” UNH President Jim Dean says. “This is truly an unprecedented situation, and we are fortunate to be in a position to make important contributions to New Hampshire’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The strength and compassion of our community is remarkable. We are all proud to make such a positive impact and to help our state through an incredibly difficult time.”

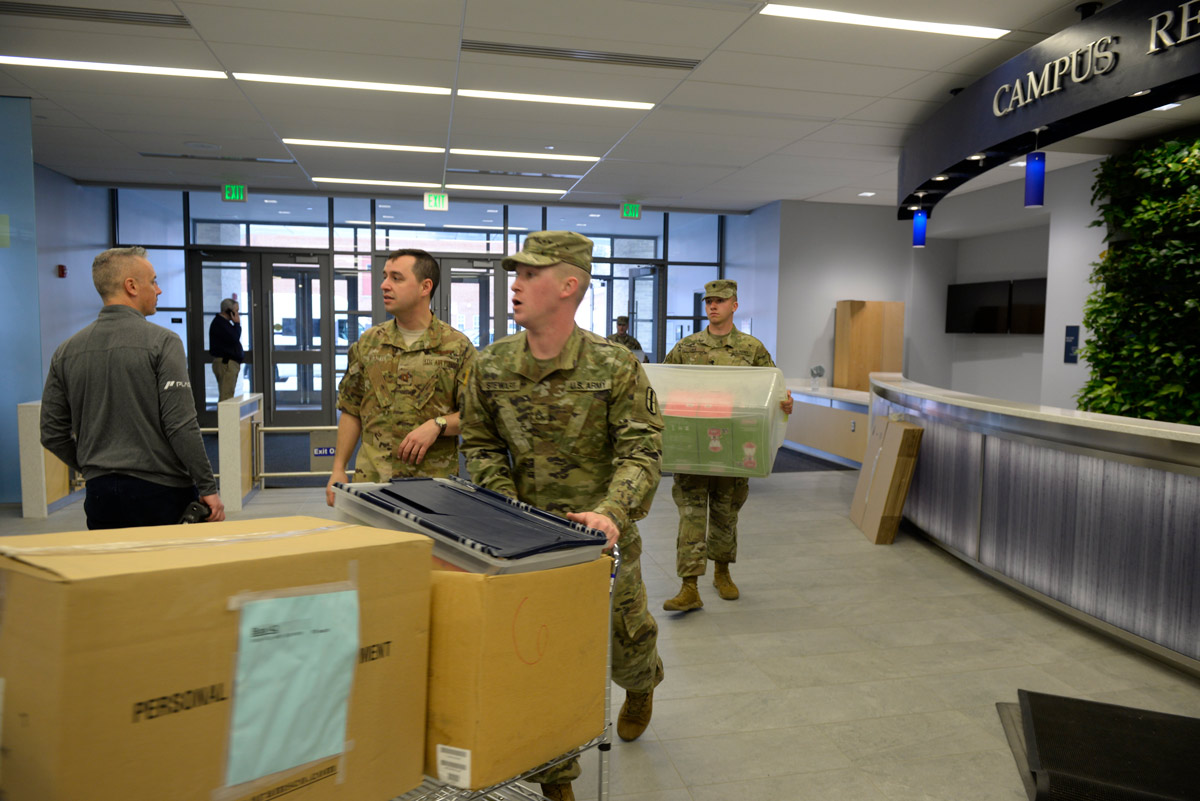

In anticipation of medical facilities potentially reaching maximum capacity with surges of patients, the goal was to create space at the Hamel Rec Center to treat those who were well enough to be discharged from the hospital but not yet recovered enough to return to their homes. The undertaking provided a blueprint that the National Guard followed in building similar sites throughout New Hampshire. Kruger and his team worked on four such sites, including those at NHTI in Concord and at Keene State, setting up more than 800 beds in total. Kruger says more than 2,000 beds were set up as surge capacity at 15 sites throughout the state.

“It was really impressive the way UNH stepped up and was willing to make anything happen to support these local hospitals,” says Kruger, whose team assembled cots, created isolation rooms in racquetball courts and used dance studios as storage for oxygen machines. “What came out of it was a model, sort of a proof-of-concept of how to build this partnership between the community and the hospitals, and what we were able to accomplish at UNH we exported across the state. We had all the logistical requirements that we needed to be able to replicate this elsewhere.”

“What was really great about this was we didn’t have to drag anyone along — all we had to do was say, ‘these are the tasks that need to be completed right now,’ and everyone sprang into action and did it,” Dean says. “My wife is a UNH alum, my older son is an alum and was student body president, my younger son is here as a freshman in the engineering program — we’re a Wildcat family, and this was one of the proudest moments for me at UNH.”

Thanks in part to some foresight from the police chief following a previous international health crisis — the H1N1 influenza virus in 2009 — UNH was also uniquely well-positioned to donate valuable personal protective equipment to several medical facilities. In the aftermath of H1N1, Dean helped spearhead the gathering of PPE such as gloves, surgical masks and N-95 respirators. When COVID-19 began to spread, various other labs and departments around campus made supplies available, as well, and the collaboration resulted in 45,000 pairs of gloves, 11,000 surgical masks, 4,800 N-95 respirators, 216 protective gowns and 38 Tyvek suits being distributed to hospitals and health care facilities throughout the region and made available to first responders in Newmarket and Dover and caregivers at Durham’s RiverWoods retirement community.

“We are here for UNH, we are here for the community around us, and we’re here for our state and the region,” Dean says. “It’s like we never skipped a beat.”

Paul College’s Center for Family Enterprise and New Hampshire Small Business Development Center (SBDC) have been right in the heart of that battle, finding ways to help New Hampshire small businesses survive — and potentially find new ways to thrive — as they navigate the uncertain waters.

As the pandemic broke, the Center for Family Enterprise was there to provide a sounding board and actionable recommendations to business owners. The SBDC was equipped to provide similar assistance, working with more than 1,300 businesses by mid-April while providing individualized advising and other resources specific to staying on course through the crisis.

Both organizations plunged immediately into the fray, altering existing successful models to fit the rapidly changing needs of their members and clients.

The SBDC created a “COVID-19 Assistance” page on its website — which saw more than 10,000 page views in its first three weeks online — that points toward specific resources around items like the Small Business Paycheck Protection Program and other coronavirus-related topics. It also began offering online training and webinars related to COVID-19, including industry-specific deep-dives in hard-hit areas like retail, professional services, manufacturing and restaurants.

The Center for Family Enterprise likewise leaned on its signature personal touch while adapting its model of assistance delivery. One of its offerings, a CEO forum bringing business leaders together in focused peer groups to discuss issues across industries, shifted online via Zoom. The center also tapped its resource partners and sponsors to facilitate weekly webinars led by experts in legal, financial and other industries, and created an online COVID-19 Family Business Resource guide with insight from CPAs, lawyers, financial advisors and charitable foundations, among others.

The most recent cohort of nursing graduates is entering the workforce under truly unique circumstances. The pandemic has made it more difficult to spare time for training and immediate on-the-job immersion, which has significantly stretched — and in some cases virtually halted — the onboarding process.

Regardless of the pace of entry, though, more than half of those recent graduates stayed in New Hampshire to begin their professional journey, joining a faction of fellow alums who are already battling the pandemic from the state’s front lines.

“The thing I am most proud of our UNH graduates for is that they are eager to enter the workforce and they understand their social responsibility and the social contract we have — that with that, we have a duty and a responsibility to serve and to understand that we are always working to minimize risk for everyone,” says Gene Harkless, chair of the UNH nursing program.

UNH has developed longstanding strong relationships with many Seacoast health care organizations – and numerous others statewide – placing students there for clinical experiences prior to graduation, and often seeing students receive offers for full-time positions after graduation.

More than 70 percent of UNH nurse practitioner graduates work in New Hampshire. Additionally, the university has been awarded a grant to train nurse practitioners and place them in rural and underserved areas of the state (the grant offers funding for students in the last 12 months of their program who live in or complete at least six months in a rural or underserved area during clinical practicums and then agree to practice in a rural or underserved area after graduation).

Harkless looks forward to continuing – and building on – those relationships in the new reality.

“COVID will have fundamentally changed how many of these organizations provide care, how they are staffed and how they respond to the community. It challenges us as educators across all of health and human services to figure out how we can best align our educational approach with their practice needs, because we are preparing the next generation of clinicians for the state,” Harkless says. “We are working on ensuring that our students are well-prepared as they go into the clinical arena. We work hard to partner with these organizations to make sure what we’re preparing students to do is what the agencies need, now and into the future.”

According to the New Hampshire Business Review, 15 such printers were being utilized by eight UNH staff and one alum as of early April, as part of a collaboration with the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, which was also producing headbands — and attaching them to the shields for distribution to medical facilities in New Hampshire, Maine and Massachusetts. The NHBR report noted that more than 300 headbands had been created by April 2.

Esewhere at UNH, civil and environmental engineering professor Jim Malley and graduate student Castine Bernardy teamed up to perform research — and share knowledge — on the ways in which ultraviolet light can help disinfect N95 respirator masks for healthcare workers and first responders. Though the masks are designed for one-time use, the use of UV light can help extend a mask’s lifespan if necessary if supplies become hard to come by.

Bernardy, who was in The Netherlands working on a wastewater reuse project when the COVID-19 pandemic forced her return home after a month, has been conducting much of the research in her mother’s basement.

Malley notes that Bernardy had been appointed as the youngest member of the International UV Association’s COVID-19 task force, and that her research efforts have been recognized throughout the country by medical professionals putting her findings to use. “She is a great example of what UNH can offer our hardworking students during extraordinary times,” Malley says.

Many of the faces he saw while performing his work were the same ones he worked with as a student, and he even drew on some of the lessons he learned in a UNH classroom.

“It was kind of cool to be back on campus feeling like all that organizational behavioral training I received at UNH was actually playing out to help unify the community to develop a plan,” Kruger, who referred to his organizational behavior class as probably the most useful course he’s ever taken, says. “Everything we do is about people, and that class is all about getting people to work together.”

“My reflection after this is all over is that we can solve anything. When we get back to whatever the new normal is, I am going to remind people of that,” Dean says. “I think there is no limit to human ingenuity, and when we all come together as a collective community to address a problem, I truly believe there is nothing here at UNH that we can’t solve or make better.”