Dave Mackey ’92

Connor Roelke ’14

Catherine “Cassie” Heppner ’95

hose unfamiliar with UNH could look at three major issues confronting us — racism, COVID-19 and financial losses triggered by the pandemic — and call it a perfect storm. Indeed, these are serious challenges and addressing them requires the support of everyone across the university. But today, I am full of optimism for UNH’s future because of the character of our community, including our alumni.

On June 7, I attended a student-led Black Lives Matter rally in Durham. I was so proud to watch hundreds of students, faculty, staff, alumni and supporters gathering peacefully, and I was deeply humbled to hear speakers share their perspectives on issues of racism, racial injustice and inequity that our nation, and even our university, still struggle to confront. It reminded me of the great civil rights marches of the 1960s, and Martin Luther King Jr., who said, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

Kristin Waterfield Duisberg

Design Director

Kasey Glode

Designer

Valerie Lester

Current Editor

Jody Record ’95

Class Notes Editor

Allison Battles ’02

Contributing and Staff Writers

Ali Goldstein

Colleen Flaherty ’09, ’10G

Karen Hammond ’64

Dave Moore

Michelle Morrissey ’97

Brion O’Connor ’84

Beth Potier

Contributing and Staff Photographers

Stephen Cloutier

Susan Currie ’88

Henry Duisberg

Caryn Crotty Eldridge ’93

Jeremy Gasowski

Ralph Morang ’72

Vinny Mwano ’15

Lisa Nugent

Gil Talbot

Matt Trappe

◆

Editorial Office

15 Strafford Ave., Durham, NH 03824

alumni.editor@unh.edu

Publication Board of Directors

James W. Dean Jr.

President, University of New Hampshire

Debbie Dutton

Vice President, Advancement

Mica Stark ’96

Associate Vice President,

Communications and Public Affairs

Susan Entz ’08G

Associate Vice President, Alumni Association

Heidi Dufour Ames ’02

President, UNH Alumni Association

◆

UNH Magazine is published three times a year by the University of New Hampshire, Office of University Communications and Public Affairs and the Office of the President.

© 2020, University of New Hampshire. Readers may send letters, news items and email address changes to alumni.editor@unh.edu.

ack in March, when COVID-19 reached the United States and UNH joined schools and businesses across the country in shifting the majority of its daily work to a remote model in the interest of “flattening the curve” and limiting the spread of the highly contagious virus, I knew right away that certain stories we’d planned for the spring/summer issue would have to wait. The COVID-19 pandemic was far too disruptive, and far too significant a historic event, not to be documented by UNH Magazine. Two of the three features in this issue — “A World on Pause” and “UNH on the Frontlines” — were born out of that shift.

What I didn’t immediately grasp, however, was the impact the pandemic would have on our ability to print. COVID-19 has hit the bottom line of colleges and universities nationwide, many of which are choosing to suspend expenses that include their alumni magazines until their future financial picture is more certain. It’s a testament to the value the University of New Hampshire places on its connections to its alumni, and the spirit of innovation and ingenuity that has driven it for more than 150 years, that the decision was made to continue publishing UNH Magazine — for now, in digital form.

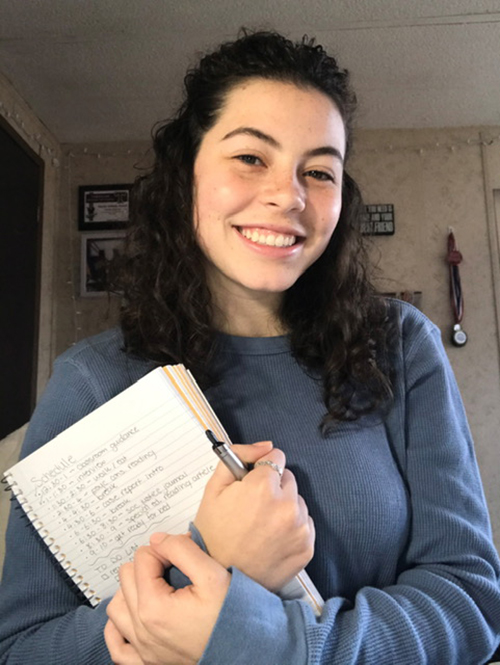

It’s okay, she figured. She’d go back to substitute teaching and working at an afterschool program to help make ends meet. But then schools started to close — first for two weeks, then for two more. Then came stay-at-home orders, and school closures into May. As someone who contributes to her family’s household costs and pays many of her own expenses, she started to panic.

“Those other jobs were my last resort; typically, I have two jobs at a time to stay afloat,” Peguero explains. “All of a sudden, I lost all of my jobs.” She says in these extraordinary times, there’s no shame in asking for assistance. “I mean, we all need help, right? It’s really important to put yourself out there, to think ‘this is something that I need, and it’s okay.’”

ome historical references place the first use of the expression “the show must go on” back in the 1800s, when circus performers continued their acts regardless of tigers on the loose or falls from the trapeze. The phrase has been repeated throughout the years to describe just about any activity that refuses to be deterred by circumstances. So it was only fitting that theatre and dance professor David Kaye and his students would apply the thinking to their production of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” which premiered via Zoom April 16, 17 and 18.

Kaye has been using Zoom for about two years to hire and rehearse actors around the country for UNH Power Play, the department of theatre and dance’s professional applied theatre company. He’s also used Zoom for other projects. “But this went way beyond that,” he says. “The students and I pretty much made this up as we went along.”

n her application to become a 2020 Truman Scholar, Abrita Kuthumi ’21 proposed an idea that would provide educational resources for the lowest caste group in Nepal. She mapped out a plan offering economic assistance as well as support for students who face social challenges. She called the initiative “Daylight.”

“I named the program in the spirit of how sunlight hits people all the same, without discriminating against gender, income, caste and other social identities,” says Kuthumi, who moved to New Hampshire from Nepal when she was 10. “With the privilege of having an American education at UNH, I want to help disadvantaged social groups in developing countries receive an education.”

A political science and international affairs major, Kuthumi has traveled to Korea twice on Critical Language Scholarships. She also received the Helen Duncan Jones Award, The Washington Center President Council’s Scholarship, a TRIO scholarship and an Undergraduate Research Conference Award of Excellence. She learned she had been named a Truman Scholar — the university’s fifth — from Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Wayne Jones via Zoom.

hen Lauren Banker ’13, Alex Freid ’13, Emily Spognardi ’14 and Erica Vazza ’14 walked into the Gables community room in May 2011, they beheld dozens of lamps, couches and other dorm items. “It looked like a pawn shop,” recalls Spognardi.

“We knew students threw out a lot that could be reused,” adds Vazza. “We didn’t know if they would choose to donate it.”

Donate it they did, and by so doing helped solidify an idea that became Trash 2 Treasure (T2T), a student-led sustainability initiative to keep useful items out of the landfill and save students and the university money. A decade later, the program is the model for more than 400 universities that have implemented similar efforts on their own campuses.

or many students, presenting monthslong research at UNH’s Undergraduate Research Conference (URC) is among the highlights of their college careers. Indeed, the program celebrated its 20th anniversary in April 2019 with more than 2,000 students presenting work over the course of 13 days. When campus closed March 18 and students were sent home to complete the spring semester remotely, it seemed inevitable that the 1,858 students who had registered to share posters, performances and projects at this year’s conference were bound for disappointment — but with a little ingenuity and the dedication of groups across campus, for the most part, that wasn’t the case.

Within a day of the university’s closing, the URC’s organizers in the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research had made the first move to take the conference virtual. “We had very little time to shift gears, identify one shared virtual platform that would work for most if not all 20-plus events, and work out the logistics,” says Hamel Center administrative director Molly Doyle.

By April 1, with the help of UNH Academic Technology, the virtual platform was identified. An online gallery to accommodate individual URC events was created, and guidelines were drawn up to aid faculty mentors and coordinators in shepherding students through the process of reimagining their in-person presentations for a virtual format. Students presented and recorded their projects remotely, then loaded them to the virtual platform for “visitors” to view at their convenience.

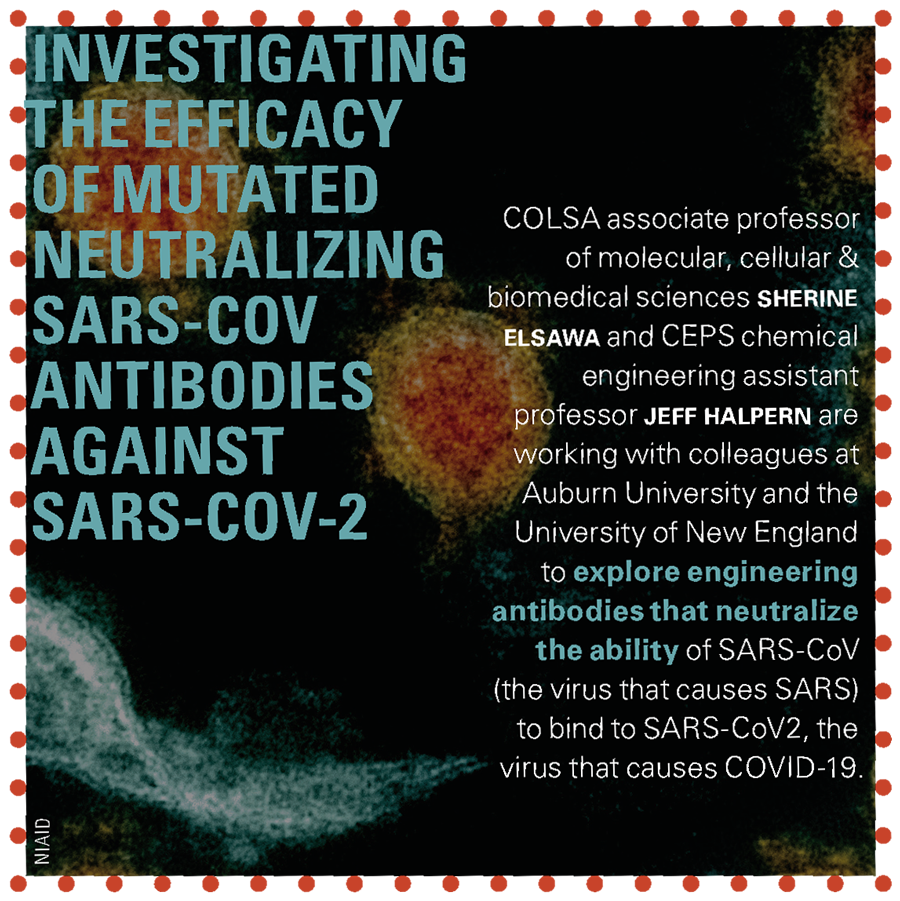

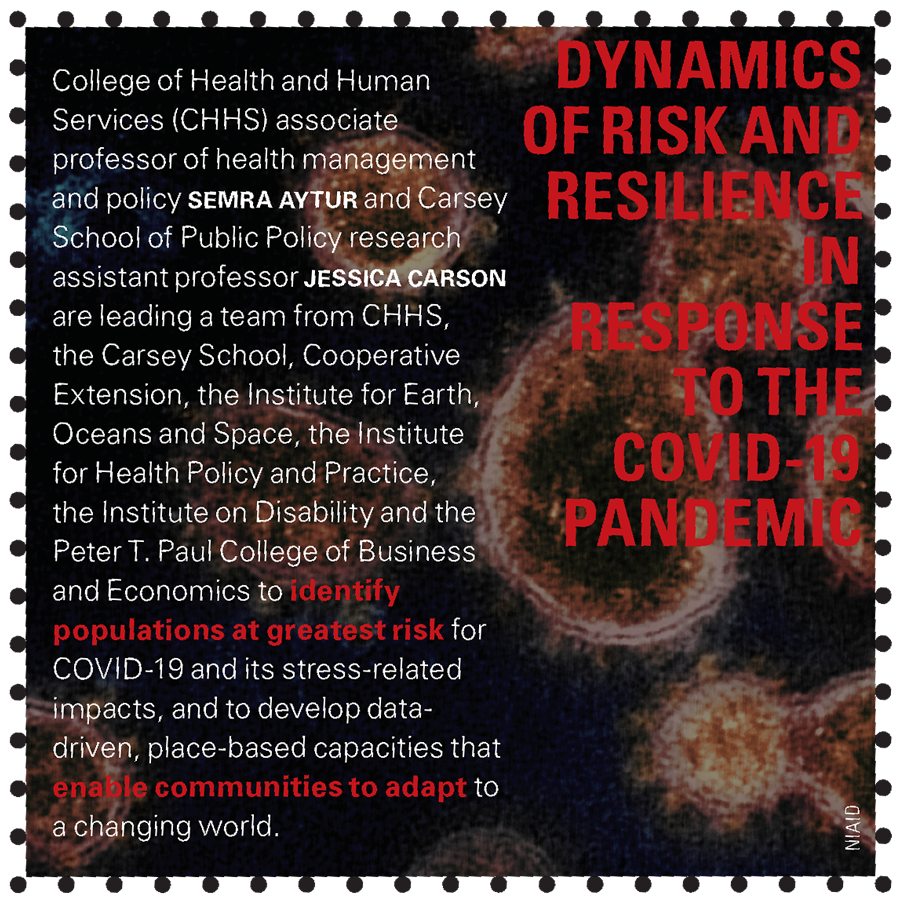

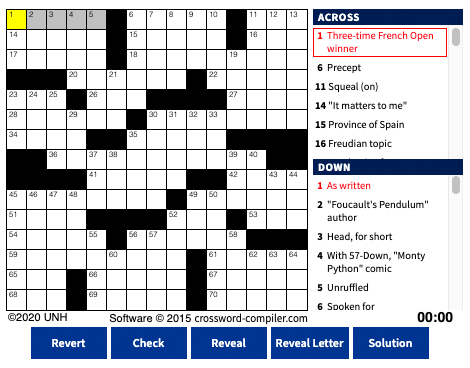

ven as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered campuses and compelled students and faculty members alike to learn new ways of engaging, it brought to the forefront one of UNH’s core strengths — or make that a CoRE strength: interdisciplinary collaboration. Launched in 2017, the Collaborative Research Excellence (CoRE) initiative represents a range of funding opportunities that reinforce a broad culture of interdisciplinary exchange, collaboration, planning and support across departments and programs at UNH. In response to COVID, some 23 interdisciplinary groups brought forward CoRE proposals for projects to address public health and welfare challenges related to the pandemic. Six of those are currently underway, harnessing expertise from across the university in fields as diverse as microbiology, digital literacy, environmental engineering and public health.

“The COVID-19 pandemic presents challenges that can only be solved through multidisciplinary collaborations,” says Marian McCord, senior vice provost for research, economic engagement and outreach. “The proposals were outstanding, and our research development team is committed to assisting each team in seeking external funding to support the proposed work.” McCord’s office and that of UNH Provost Wayne Jones will support each project with a one-year grant of $30,000.

t’s a joke that’s accompanied nearly every blizzard and blackout since the return of soldiers from World War II ushered in the United States’ first baby boom in the 1940s: brace yourselves for maxed-out maternity wards in nine months. But while punsters already have a handful of nicknames at the ready for the population that will join the world in early 2021 —coronials, anyone? Baby zoomers?— UNH’s Class of 1940 Professor of Sociology Kenneth Johnson thinks a spike in births is unlikely. In fact, he says the United States will likely see its birth rate continue to decrease.

“There’s no way that the number of births is going to go up,” says Johnson, senior demographer for the university’s Carsey School of Public Policy. “This is not the kind of environment in which people say, ‘let’s bring a child into the world now.’”

Johnson says a number of factors were already causing a slowing of the U.S. population’s rate of growth even before COVID-19 hit. Now, financial uncertainty related to the pandemic and the attendant shutdown of industries and businesses across the United States are making it more likely for couples to postpone the decision to start a family — or possibly to forgo parenthood entirely.

Johnson points to the economic downturn that began in 2007 as evidence. “Fertility dropped substantially,” he notes. “That’s not unusual. That often happens during difficult economic times.” What is unusual, however, is that the birth rate didn’t bounce back during a subsequent decade-plus of relative stability and economic growth. At the same time, the United States’ death rate has increased — primarily because the population is getting older, and the mortality rate of older individuals is higher. While for now the U.S. population continues to maintain a natural increase — a higher absolute number of births than deaths every year — the margin between those numbers is closing, a pattern that the current pandemic is likely to accelerate.

Johnson says it’s too soon to say yet what the long-term impact of this trend will be on the nation’s population. But last year, the U.S. population growth rate was the lowest since 1919—during the Spanish flu pandemic. With more than 100,000 deaths already from the coronavirus and little likelihood of any increase in births, it is very likely that the population growth rate will diminish again this year.

Ten other student-athletes were recognized for their achievements at this year’s Senior Showcase. Kaylan Williams ’20 of the women’s soccer team and Nelson Thomas ’20 (football) and Jack Crawford ’20 (men’s cross country/track and field) earned the Cathy Coakley Community Involvement Award. Swimmer Allison Stefanelli ’20 earned the Coaches Award, and women’s hockey player and men’s track and field athletes Abby Chapman ’20 and Edward Speidel ’20 claimed the Athletic Director’s Award for Academic Excellence. Bauer was the male recipient of the Performer of the Year Award, alongside Anna Metzler ’20 of swimming and diving. Rounding out the honors were Corinne Carbone ’20 (swimming and diving) and Evan Gray ’20 (football), who received the Tina True Award and Rookie of the Year awardees Maura Verleg ’20 (field hockey) and Max Brosmer ’20 (football).

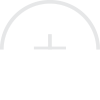

Flatiron Books,

August 2020

n an idyllic summer day in 1878, just after the traveling Ludwig Zirkus wraps up its afternoon performance, a hundred-year wave bears down on the island of Nordstrand, carrying away all but the youngest of Lotte and Kalle Jansen’s four children. As life goes on for the other inhabitants of the German island, Kalle deals with his grief by joining the Zirkus to tend to its animals. Lotte, having lost the will to care for her surviving son, Wilhelm, is taken in by the nuns at St. Margaret’s Home for Pregnant Girls. Soon, Lotte comes to depend on Tilli, an 11-year-old St. Margaret’s resident whose growing attachment to the infant Wilhelm soothes her own grief after her illegitimate newborn is whisked away, and Sabine, the Zirkus seamstress whose teenage daughter remains perpetually childlike. Even as she creates this new family for herself, Lotte finds herself sinking deeper into the myths of her island, which hold the possibility that her lost children are still alive.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

July 2020

n the months leading up to the 1948 presidential election, there was exactly one person who believed that Democratic incumbent Harry Truman could continue to hold the office he’d stepped into when FDR died suddenly a few short months into his fourth term — Truman himself. The country he sought to maintain was deeply fractured: Racism was rampant, foreign relations were complicated and fraught, and Truman was up against a Republican challenger, Thomas Dewey, who had effectively been anointed as the next president by the national press. In his follow-up to 2017’s “Accidental President,” Baime takes readers inside four campaigns — Truman’s, Dewey’s, Henry Wallace’s Communist-sympathizing Progressive Party and Strom Thurmond’s unapologetically white supremacist “Dixiecrats” — to witness the inner workings of America’s first postwar election and a battle for what Truman called “the very soul of the American government.” Set against a backdrop of impeachment headlines, fears that Moscow was trying to interfere with the election, a president in a feud with the press, unprecedented vitriol in the political dialogue and more, Baime’s latest is not only a vivid history lesson, it’s also a remarkably timely exploration of the politics of politics and their consequences.

Read more about Baime, his book and the role UNH played in shaping his successful writing career in UNH Magazine’s exclusive online interview

Flatiron Books,

August 2020

n an idyllic summer day in 1878, just after the traveling Ludwig Zirkus wraps up its afternoon performance, a hundred-year wave bears down on the island of Nordstrand, carrying away all but the youngest of Lotte and Kalle Jansen’s four children. As life goes on for the other inhabitants of the German island, Kalle deals with his grief by joining the Zirkus to tend to its animals. Lotte, having lost the will to care for her surviving son, Wilhelm, is taken in by the nuns at St. Margaret’s Home for Pregnant Girls. Soon, Lotte comes to depend on Tilli, an 11-year-old St. Margaret’s resident whose growing attachment to the infant Wilhelm soothes her own grief after her illegitimate newborn is whisked away, and Sabine, the Zirkus seamstress whose teenage daughter remains perpetually childlike. Even as she creates this new family for herself, Lotte finds herself sinking deeper into the myths of her island, which hold the possibility that her lost children are still alive.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

July 2020

n the months leading up to the 1948 presidential election, there was exactly one person who believed that Democratic incumbent Harry Truman could continue to hold the office he’d stepped into when FDR died suddenly a few short months into his fourth term — Truman himself. The country he sought to maintain was deeply fractured: Racism was rampant, foreign relations were complicated and fraught, and Truman was up against a Republican challenger, Thomas Dewey, who had effectively been anointed as the next president by the national press. In his follow-up to 2017’s “Accidental President,” Baime takes readers inside four campaigns — Truman’s, Dewey’s, Henry Wallace’s Communist-sympathizing Progressive Party and Strom Thurmond’s unapologetically white supremacist “Dixiecrats” — to witness the inner workings of America’s first postwar election and a battle for what Truman called “the very soul of the American government.” Set against a backdrop of impeachment headlines, fears that Moscow was trying to interfere with the election, a president in a feud with the press, unprecedented vitriol in the political dialogue and more, Baime’s latest is not only a vivid history lesson, it’s also a remarkably timely exploration of the politics of politics and their consequences.

Read more about Baime, his book and the role UNH played in shaping his successful writing career in UNH Magazine’s exclusive online interview

A.J. Baime

A.J. Baime

Frontlines

en Kruger ’03 can flip through memories from his time on the UNH campus like he’s thumbing through crates of used records, pausing for just a second to revel in each one before moving effortlessly to the next.

He spent one of his undergraduate years as student body president, relishing his time as a leader among his classmates and interacting with university administrators. He completed the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program, taking the first steps toward a fulfilling career in the New Hampshire National Guard, where he has achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel. He fondly recalls days and evenings spent hanging out in the Memorial Union Building (MUB), which he refers to as “the nexus” of social activity on campus.

But Kruger’s mental archives don’t end at graduation — in fact, if anything, the scenes he’s added since he earned his degree are even more vivid.

Frontlines

en Kruger ’03 can flip through memories from his time on the UNH campus like he’s thumbing through crates of used records, pausing for just a second to revel in each one before moving effortlessly to the next.

He spent one of his undergraduate years as student body president, relishing his time as a leader among his classmates and interacting with university administrators. He completed the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program, taking the first steps toward a fulfilling career in the New Hampshire National Guard, where he has achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel. He fondly recalls days and evenings spent hanging out in the Memorial Union Building (MUB), which he refers to as “the nexus” of social activity on campus.

But Kruger’s mental archives don’t end at graduation — in fact, if anything, the scenes he’s added since he earned his degree are even more vivid.

It’s safe to say “turning the site of my college fitness center into a makeshift hospital during a global pandemic” wasn’t on the list of memories Kruger anticipated making at UNH.

But that doesn’t make it any less gratifying.

“All the stops were pulled out by UNH to make this happen, and the National Guard was there to facilitate and provide direction. It was definitely a source of pride,” Kruger says. “It was inspirational to see that as a community, we can be stronger than COVID-19. The attitude of the university was, even if this helps save one person, it’s worth it.”

That attitude is what fueled the university to spring into action almost immediately as COVID-19 began spreading, prompting significant contributions to mitigate the impact throughout the state.

or many, the word “politics” conjures up negative images of entrenched lawmakers bickering across party lines. Laconia Mayor Andrew Hosmer has a solution for that.

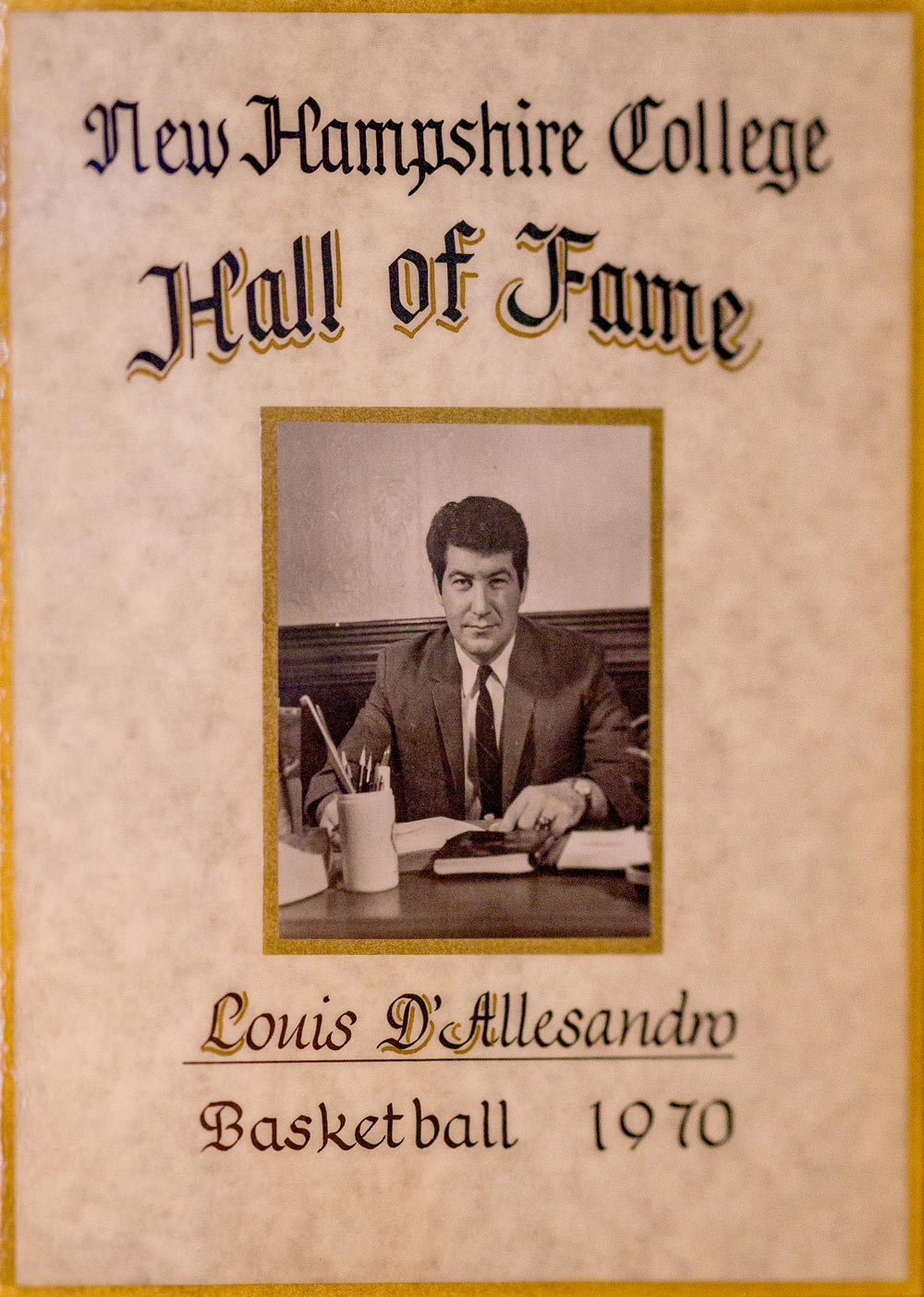

“If someone were to say to me, ‘I hate government and I hate everyone in government,’ my response might be, ‘If you can give me 30 minutes I’d like to introduce you to my friend Lou D’Allesandro, and then I want you to give me your opinion afterward,’” Hosmer says. “Because with Lou it isn’t about self-congratulations; it isn’t about collecting awards. It really is about serving others. He’s an old-school public servant.”

D’Allesandro, 81, has been serving the people of New Hampshire for the better part of five decades. He’s been a member of the state’s House of Representatives and Executive Council, and he’s currently serving his 11th term in the State Senate. He’s been a champion of education as a long-time member of the New England Board of Higher Education — where he recently completed a nearly 20-year run — and in the private sector as a top-level adminstrator at three colleges.

It’s a remarkable list of accomplishments, and they all have some roots at the University of New Hampshire.

“Going to UNH turned out to be my life-altering experience,” D’Allesandro says.

One of his most important, and entertaining, life-altering moments at UNH came in the spring of 1960 when he was a junior. John F. Kennedy was making a campaign stop in Durham and D’Allesandro was eager to see the senator from Massachusetts, who had also been the U.S. Congressional Representative for the East Boston neighborhood where D’Allesandro was born and raised.

losed campuses and makeshift medical units. Vacant stores and streets and beaches. As the novel coronavirus COVID-19 spread across the globe earlier this year, it prompted dramatic changes in wide-ranging landscapes. Once-empty spaces that were now full. Once-full spaces that were suddenly empty. While this worldwide pandemic has virtually halted 21st-century life as we know it, a number of UNH alumni photographers have joined other essential workers whose service remains unflaggingly public to document these altered vistas. From the United Kingdom to the United States, from Maine to Washington, D.C., to Florida, their images will serve to chronicle this pivotal moment in history for years to come.

Don’t see a column for your class? Please send news to your class secretary, listed at the end of the class columns, or submit directly to classnotes.editor@unh.edu. The deadline for the next issue is September 15.

9 Rickey Drive

Maynard, MA 01754

bryantnab@yahoo.com; 978-501-0334

rian “Murph” Murphy ’86 grew up in Dover, New Hampshire’s hockey ecosystem, where everything from family stick-and-puck sessions and school competitions to weekend nights at UNH watching the Wildcats take on the nation’s best collegiate teams and the Big Show — the Boston Bruins — are connected.

For a kid ensconced in the life, the Stanley Cup Finals were something special. “My parents always let my brother Mike and I stay up, no matter how late, to watch the official presentation of the cup on T.V.,” recalls Murphy. “There was nothing like it in all of sports . . . the way the guys lined up to shake hands just moments after going so hard at each other for so long.”

Murphy played at Dover High under coach Dan Raposa ’83, ’87G. At UNH, he didn’t try out for hockey, but he stayed in the sport by playing in pick-up games and working the Zamboni at Dover Ice Arena. It was at the arena that he got his “this-should-be-my-life!” calling. “I was cleaning the ice between games. Afterward, I asked one of the refs how much he got paid. When he told me, I thought, “Hmmm, this just might work!” When Raposa, who became an NCAA hockey official himself, strongly encouraged Murphy’s interests, his future course was set.

y spring 2015, Dave Mackey ’92 had a hard-earned reputation for toughness. The Maine native and onetime UNH soccer player was a decorated ultra-runner, competing in races of 100 miles or more and garnering multiple runner of the year awards. He was a physician’s assistant, married to fellow Wildcat Ellen Bilek ’92 and father to two young children, living in the endorphin capital of Boulder, Colorado.

But Mackey’s life changed forever on May 23, 2015, the day he headed out for a typical three-hour training run through the hills surrounding Boulder. On Bear Peak, he stepped on a boulder he’d pushed off of hundreds of times before. This time, however, the rock dislodged, loosened by days of heavy rain. “It was about a 300-pound rock,” Mackey recalls. “I tumbled about 60 feet and landed on my back, amongst some scree.” He survived the fall, but the boulder tumbled behind him and came to rest on his left leg, pinning him down and creating an open tibial fracture.

uring his senior year at the Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics, Connor Roelke ’14 witnessed the “ridiculous trajectory” of the then-emerging craft beer scene and had an epiphany about nitrogen kegerators. It just didn’t happen to be about beer.

No, Roelke wanted to brew coffee. Specifically, nitrogen-infused cold brew coffee. So he developed a business plan, prototype and pitch for a company called NOBL Beverages and entered Paul College’s annual Holloway Prize Competition, taking first place in his category. That was enough to convince him he could make a go of his business in the real world, and shortly after graduation Roelke found himself with a driveway’s worth of kegerator equipment — and the need for more capital and plain-old persistence than he’d initially anticipated.