Photography by Neil van Niekerk

e all have priorities and dreams, but it’s where these intersect that life lessons are forged. It took Donna Schleinkofer Lynne ’74 all of one semester, not even that long, really, to learn a life lesson she’d never forget: Sometimes a priority outweighs a dream.

A three-sport high school athlete and academic standout from New Jersey, Lynne came to UNH with aspirations to play field hockey and tennis while double-majoring in economics and political science. The only hitch was that she’d have to work her way through college, as family support wouldn’t come close to covering her expenses.

Photography by Neil van Niekerk

e all have priorities and dreams, but it’s where these intersect that life lessons are forged. It took Donna Schleinkofer Lynne ’74 all of one semester, not even that long, really, to learn a life lesson she’d never forget: Sometimes a priority outweighs a dream.

A three-sport high school athlete and academic standout from New Jersey, Lynne came to UNH with aspirations to play field hockey and tennis while double-majoring in economics and political science. The only hitch was that she’d have to work her way through college, as family support wouldn’t come close to covering her expenses.

The choice was as painful as it was inevitable. Although she would continue to attend games as a spectator, Lynne said goodbye to UNH field hockey as a player. Instead, she focused on her studies, loading up on extra courses so she could graduate a semester early — with high honors. Along the way, she met faculty mentors who would change her life.

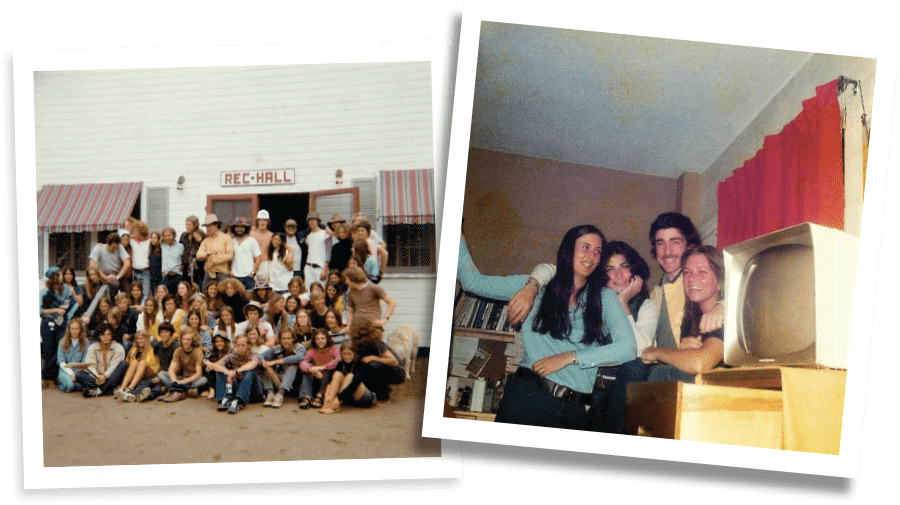

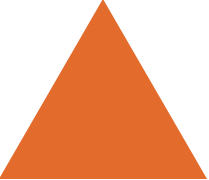

In political scientist David Larsen, Lynne found a mentor who catalyzed her activist side — she was, after all, “a child of the ’60s” — and gave her a job as researcher with the New Hampshire Council on World Affairs. The Council’s mission was to bring greater awareness of international politics and affairs into traditional New Hampshire classrooms, where, Lynne recalls, “international studies weren’t reflective of the political turmoil in the world.” In business professor Nina Rosoff, Lynne discovered “the first woman I ever met who wasn’t teaching children or subjects like art or literature, somebody about whom I remember thinking, ‘She’s the kind of woman I want to be.’”

For Lynne, this would ultimately mean attaining a position from which she would be able to help others, starting with careers in government service and healthcare leadership. It also would mean circling back to her alma mater, where she would establish endowments to support female student-athletes, in the hope that they wouldn’t have to make the hard choice that she had.

ollowing her graduation from UNH, Lynne earned a master’s degree at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. And then she did something that not everybody with her credentials does: she went into New York City government.

Lynne is an unapologetic fan of government, or to be precise, government workers, whom, she believes, “are a much-maligned group who are dedicated to making a difference in peoples’ lives and deserve better.”

A party she attended with a friend in the late ’70s captures the feeling. “It was a typical party of professional people where you stand around and talk about what you do,” Lynne remembers. “My friend and I stuck close to one another, and I would marvel as she told people she wrote jingles for fruit drinks. They lapped up every word. They couldn’t hear enough about what it was like working on Madison Avenue. When my turn came to tell them what I did — improving healthcare, labor relations and municipal operations — their eyes glazed over, [even though] we were helping the city through some extremely desperate economic times and our work was featured in The New York Times virtually every day. Drove me crazy!”

Child of the ’60s or not, Lynne chose to work in public service because she believed she could effect change more powerfully “as a participant on the inside than as a protester on the outside.” In New York, she was on the inside for 20 years, helping see the city through bankruptcy even as she earned her doctorate in public health from Columbia University as a part-time student. Eventually, she had an opportunity to try her own luck in the business world and joined the private insurance company Group Health Incorporated, where she rose to the rank of president before pulling up stakes and moving to Colorado to join Kaiser Permanente, one of the country’s largest not-for-profit healthcare companies. Lynne worked as an executive for Kaiser from 2005 to 2016 and says she looks back on her years in Colorado as some of the best of her life — in no small part because of the challenges they provided, which included earning the trust and respect of her western colleagues. The native East Coaster spent her first 100 days in Denver giving herself a crash course in the state’s business and political power structure, meeting with 100 legislators, mayors, business and nonprofit leaders and other movers and shakers who would become her allies in the years to come.

Those allies would help her achieve one of her proudest accomplishments at Kaiser, early in her tenure: taking up the cause of the state’s many uninsured citizens. In a two-year period, she oversaw the expansion of access to Medicaid and small individual health plans that fell under the Affordable Care Act into rural and underserved areas, increasing plan membership by 15 percent. The Denver Business Journal thought highly enough of her contributions to name her as one of the city’s “Outstanding Women in Business” in 2008.

As COO, Lynne’s work focused on performance management for the entire state and the use of customer service feedback to assess the quality of statewide services. “People say you should be careful about asking for feedback because you just might get more than you bargained for,” she says. “But I’m a risk-taker. When I hear the little voice in my head running contrary to what other leaders all seem to agree on, I want to go right to the source, the stakeholders, the people themselves.”

In 2015, Modern Healthcare magazine rewarded her risk-taking by including her as one of the “Top 25 Women in Healthcare” in the United States.

The Rocky Mountain state’s business and political spheres weren’t the only summits Lynne scaled. A lifelong outdoors enthusiast, she also began to spend her weekends getting into bicycle gear to traverse the state on long-distance bike rides, or strapping on her climbing gear to conquer Colorado’s fabled mountains, successfully summitting every last one of the state’s 58 “fourteeners” — 14,000-foot mountain peaks — and down-hilling dozens of its ski mountains.

n the spring of 2019, Lynne was recruited by Columbia University, where she’d continued to lecture for many years after earning her doctorate. For a woman who had literally climbed every mountain, the Columbia opportunity proved irresistible, not least because it involved her assuming not one position but two: She accepted a double appointment as CEO of Columbia Doctors and senior vice president and COO of Columbia University Irving Medical Center. In her capacity as CEO she works with 2,000 Columbia University physicians in more than 100 primary care practices in metropolitan New York City; as COO she heads up all nonacademic departments for the medical center. And while Manhattan might not offer the geographic challenges of the Rocky Mountains, neither that nor her demanding schedule have kept Lynne from setting her sights on another legendary mountain conquest: this spring, she plans to hike to the base camp of Mount Everest.

“Sometimes, when I haven’t got my workout in yet or haven’t shopped for food, I may not feel like meeting for coffee with somebody,” Lynne admits. “Then I remember how much I appreciated getting good advice, myself. I see it as an important responsibility for women to show strength and leadership for other women to see.”

It’s the same sense of responsibility that brought her back to UNH.

In the last decade, Lynne has given generous annual fund support that has benefited the UNH athletics department year after year, including the installation of covered team benches for Memorial Field, home turf for UNH field hockey. She also has created two UNH athletics endowments that benefit female student-athletes.

The Donna Lynne ’74 Athletics Enhancement Fund provides program support to any of UNH’s women’s varsity athletic teams. The funds may be used for equipment, travel and other expenses. UNH field hockey coach Robin Balducci ’85 says gifts like Lynne’s make a meaningful difference across the athletics department, providing coaches with resources that strengthen their programs and directly impact student-athletes’ UNH experience.

Her second endowment, the Donna Lynne ’74 Scholarship Fund, provides scholarship support to one field hockey player each year, with preference given to student-athletes with a potential to become academic as well as team leaders. To date, there have been nine Donna Lynne scholars, and, by all measures, they are fulfilling their benefactor’s hopes.

Lynne must see something of herself, then, in the most recent Donna Lynne scholar: Kayla Sliz ’20, a team captain from Ajax, Ontario. Among her numerous accomplishments, Sliz was named a 2016 National Field Hockey Coaches Association (NFHCA) Scholar of Distinction and was named to the NFHCA National Academic Squad for three consecutive years. Ask her to point out her single greatest accomplishment at UNH, however, and Sliz is likely to skip over the athletic honors and tell you instead about her poster presentation at UNH’s 2019 Undergraduate Research Conference on the topic of female leadership in collegiate sports. “My poster looked at the skills and strategies of effective leadership. It was very rewarding to spend the year working hard to analyze data and get to share the results of that work with my peers,” she says.

Still . . . she’d have made a heck of a Wildcat midfielder.