Kristin Waterfield Duisberg

Design Director

Kasey Glode

Designer

Valerie Lester

Current Editor

Jody Record ’95

Contributing and Staff Writers

Callie Carr ’09

Benjamin Gleisser

Erika Mantz

Beth Potier

Keith Testa

Lori Wright ’06G, ’19G

Contributing and Staff Photographers

Ball and Albanese

William Cherry

Jeremy Gasowski

Jeffrey MacMillan

Meghan Murphy ’20

Scott Ripley

Sam Pacheco

Neil van Niekerk

◆

Editorial Office

15 Strafford Ave.,,Durham, NH 03824

alumni.editor@unh.edu

www.unhmagazine.unh.edu

Publication Board of Directors

James W. Dean Jr.

President, University of New Hampshire

Debbie Dutton

Vice President, Advancement

Mica Stark ’96

Associate Vice President,

Communications and Public Affairs

Susan Entz ’08G

Associate Vice President, Alumni Association

Heidi Dufour Ames ’02

President, UNH Alumni Association

◆

◆

UNH Magazine is published three times a year by the University of New Hampshire, Office of University Communications and Public Affairs and the Office of the President.

© 2020, University of New Hampshire. Readers may send address changes, letters, news items, and email address changes to: University of New Hampshire Magazine, 15 Strafford Ave., Durham, NH 03824 or email alumni.editor@unh.edu.

Elizabeth Burakowski, a research associate professor who studies climate science in the Institute of Earth, Oceans and Space, evaluates snow albedo — a measure of the reflection of solar radiation — with research assistant Emily Wilcox ’19 at UNH’s Thompson Farm.

Elizabeth Burakowski, a research associate professor who studies climate science in the Institute of Earth, Oceans and Space, evaluates snow albedo — a measure of the reflection of solar radiation — with research assistant Emily Wilcox ’19 at UNH’s Thompson Farm.

espite your trepidation about publishing three weighty articles, you and your staff have produced an issue of such depth that it rivals any magazine.

I really don’t have sufficient words to describe the impact of the Foley and Lenzi stories. Coupled with the“Disinformation Age” article, you’ve given any reader insight into the perils of foreign service and the overarching need to “tell the story.”

While we enjoy every issue, this one is exceptional on many levels and deserving of national recognition.

I always read from the back pages, starting with the “In Memoriam” section. I always treasure reading about the amazing “giving to society” of deceased outstanding alumni.

just read and thoroughly enjoyed the piece in the Fall 2019 edition of UNH Magazine about the current state of journalism. For years I’ve been trying to tell younger people that there is, in fact, optimism to be found in the newsgathering world, and the article expressed that nicely.

Despite the words about trust, accountability and accuracy, the author doesn’t fully explain the current level of trust people have in news media. A recent poll indicated that almost 70 percent of Democrats trust the news, while only 15 percent of Republicans do. Doesn’t that tell us something? Bias, and bias favoring the liberal side.

first heard the name Andrew Lee in 2016, when I was added to a long email thread about the independent study he’d just completed in Paul College for something called “Driven To Cure,” which someone thought was worthy of a mention in UNH Magazine. It took me a few minutes to get my head around the story: Andrew was a student; he’d somehow raised $200,000 for cancer research, it appeared, simply by owning an eye-catching performance car. It took me a few minutes longer to realize Andrew Lee wasn’t “simply” anything.

At the end of his freshman year of college, when his entire life was still seemingly ahead of him, the 19-year-old had been diagnosed with a rare, late-stage cancer that he was expected to succumb to in less than a year. Rather than withdrawing from school, he’d returned to UNH in the fall of 2015 to continue his education for as long as possible, flying home twice a month for experimental treatments. When that eventually proved too difficult to sustain, he’d sought out Paul College professor Andrew Earle to help him turn the Nissan GT-R “dream car” his parents had bought him following his diagnosis into the basis of a nonprofit to raise research funds for the treatment of cancers like his own.

ne of UNH’s most vital libraries isn’t stocked with books and periodicals. Instead, it’s home to wings and antennae, pincers and stingers. And now, a $4.3 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) will help make that “library” — along with those of 26 other research institutions — accessible to the research community and the general public.

Istvan Miko, an entomologist and research scientist in the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture, compares the 700,000 specimens in UNH’s collection of insects and other arthropods to “books in the library of life.” In 1984, the specimen count was around 300,000. Today, it’s the largest collection among all state universities in New England. And yet, as with other “libraries” around the country, its benefits have not to this point been fully realized. Researchers at other institutions haven’t had full access; interested citizen scientists can view only about 2 1/2 percent of the specimens; the information these specimens can provide about the spread of disease-carrying pathogens hasn’t been accurately mapped.

The NSF’s Terrestrial Parasite Tracker project will mobilize data and images from more than 1.3 million arthropod specimens from research collections across the United States, including UNH’s. That information will be combined with vector and disease-monitoring data from state and federal agencies, creating a portal for researchers to track past parasite distributions and their interactions with hosts to predict future changes. Purdue University is leading the effort; UNH’s portion of the grant will be used to create high-quality 3D images of its specimens and for outreach and education about how disease vectors carry and transmit pathogens.

“Having this data available will help us understand health in humans and ecosystems as well as climate change,” says Miko, who manages UNH’s collection. “If we understand the vectors of certain diseases, we can come up with models and predict what’s going to happen 20, 30 years from now.”

Making access to specimens more readily available to a broader audience is key, Miko says. At UNH, currently only about 17,000 species can be viewed online. Thanks to the NSF and the Terrestrial Parasite Tracker project, he estimates that number will increase to 250,000 by 2023.

Investment

In Minors

in december, UNH’s College of Health and Human Services (CHHS) announced a new $26.8 million preschool development grant, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to support a range of early childhood care-and education-focused initiatives. Kimberly Nesbitt, an assistant professor of human development and family studies, will serve as primary investigator on the grant, the largest ever awarded to a single faculty member in CHHS.

“While many educational and public health indicators rank New Hampshire above other states, there are disparities, particularly among New Hampshire’s most vulnerable families,” says Nesbitt, who co-led an earlier, $3.8 million grant from the same agency.

UNH will administer the grant, which will focus on children from birth to age 5, in cooperation with the New Hampshire Department of Education and the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

McCord joined the university on Feb. 3 from North Carolina State University, where she served as associate dean for research in the College of Natural Resources. A biomedical engineer with degrees from Brown and Clemson universities, her own research has been focused on the use of textiles, polymers and biomaterials for medical products, devices and implants. She cofounded one company that develops blood phosphate filtration solutions for patients with end-stage renal disease and served as cofounder and vice president for another that creates materials that are insecticidal or insect-bite-proof to protect humans against insect bites.

While McCord’s time for research in her new role will be limited, she says remaining engaged in research allows her to better relate to the day-to-day challenges that faculty face. And she’s excited about the particular challenges her own role will present.

“What UNH is doing with bringing together research, innovation, extension, engagement and outreach is really smart and very forward-thinking,” she says. “The university is poised to take great leaps and I want to be a part of that.”

McCord joined the university on Feb. 3 from North Carolina State University, where she served as associate dean for research in the College of Natural Resources. A biomedical engineer with degrees from Brown and Clemson universities, her own research has been focused on the use of textiles, polymers and biomaterials for medical products, devices and implants. She cofounded one company that develops blood phosphate filtration solutions for patients with end-stage renal disease and served as cofounder and vice president for another that creates materials that are insecticidal or insect-bite-proof to protect humans against insect bites.

While McCord’s time for research in her new role will be limited, she says remaining engaged in research allows her to better relate to the day-to-day challenges that faculty face. And she’s excited about the particular challenges her own role will present.

“What UNH is doing with bringing together research, innovation, extension, engagement and outreach is really smart and very forward-thinking,” she says. “The university is poised to take great leaps and I want to be a part of that.”

“I didn’t even know this kind of job existed”

In high school AP biology, we had to pick a project. I chose plant genetics. That’s how I discovered Darwin; Mendel. Then when I went to college, to Dartmouth, and took physics, I said, ‘Oh, this is what I want to do.’ That was my major until just after my sophomore year. Then I took a molecular genetics course and wondered why I left biology.

So, I switched my major to biology. I was working in a lab at the medical school and at my mother’s farm a couple of days a week. Senior year I decided I should look for a job. I said, I want to combine plants and genetics and I’ve been reading plant catalogues since I was a kid, so I’ll be a plant breeder. I learned I’d have to get a Ph.D. so I said, well, I’ll get one.

Studies have long shown that cows and other ruminants are significant producers of the greenhouse gas methane, contributing some 37 percent of the Earth’s methane emissions tied to human activity. In a study conducted last summer by researchers at UNH and the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station (NHAES), organic dairy cows fed kelp meal produced less methane for part of the summer grazing season. Now, these researchers are collaborating on a $3 million grant from the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund to investigate reducing methane emissions of lactating dairy cows by supplementing their diet with kelp meal and other seaweeds.

Cold Case,

Hot Science

“Over the past five years, we have focused our efforts on providing the very best education for our students,” says Paul College Dean Deborah Merrill-Sands. “Being recognized for our efforts is always a proud moment for me and our faculty, staff, alumni and students.”

There are some 500 public universities in the United States. In January 2019, President Jim Dean announced his aspiration for UNH to be among the top 5 percent of them — a top-25 public university — on nine key measures of academic success, from graduation rate for undergraduate students to research funding per faculty member. On Feb. 4, speaking to a full house of faculty, students and staff at the Hamel Recreation Center, Dean presented an update on the state of the university, UNH’s progress toward those specific metrics and the four universitywide strategic priorities supporting that aspiration.

“Even just stating these goals has already inspired people to think about UNH differently, and to raise our own sights higher,” Dean noted. The good news? On a number of the nine measures identified in 2019, UNH’s performance has improved. The challenge, however, is that many peer institutions have made improvements, as well.

Dean pointed to UNH’s graduation rate for Pell grant students — those who qualify for the highest levels of state and federal aid — as one place where this dynamic has played out. While the university’s graduation rate for these students has risen slightly, from 71.8 percent to 72.6 percent, its ranking on this measure relative to other institutions fell four places. On a different measure — student participation in high-impact educational practices (such as research, internships and service-learning projects), UNH’s ranking rose, even though student participation rate stayed steady at 81 percent. Across all nine metrics, year-over-year results support a common theme: to achieve a goal as ambitious as ranking among the country’s top 25 public universities, it’s not enough for UNH to simply continue business as usual. That, Dean noted, is where the four strategic priorities come in.

Embrace New Hampshire: UNH will make everyone in New Hampshire incredibly proud of their public flagship university. Students will grow up wanting to come to UNH, and it will be the first choice for the best and brightest students from New Hampshire and around the world. We will build collaborations that support New Hampshire’s economy and quality of life, and will be a trusted, valuable and consistent partner.

Enhance Student Success and Well-Being: Ensure that students graduate on time and are engaged and ethical global citizens, prepared to thrive in their first jobs and throughout their careers.

Expand Academic Excellence: Focus on attracting increasingly strong and diverse students and faculty from across the country and abroad. We will achieve this by being known and respected for the high caliber of teaching, research and advising across all our academic programs, as well as our distinguished research, scholarship and doctoral education worldwide.

Build Financial Strength: UNH will be a national leader in cost management and aligning its budget and resources with its strategic priorities. UNH will become more accessible and affordable for students by diversifying revenue sources and managing expenses. UNH will meet the full range of student needs by providing world-class faculty, facilities and organization.

Season

Band members made a relatively quick down-and-back of that trip, arriving the day before Thanksgiving and returning to campus on Friday. In March, approximately half the band will take on a somewhat more ambitious itinerary, traveling to Dublin, Ireland, to march in two St. Patrick’s Day parades and take in some of the local sights. They’ll be joined by more than a dozen Wildcat Marching Band alumni, who are dusting off their instruments and their set lists to commemorate the band’s centennial.

UNH’s first band actually dates back to 1906, but it didn’t start marching at football games until 1919. “The band itself has changed a lot since it started,” says Goodwin, who played trombone with the Wildcat Marching Band in her student days and now directs both the marching band and its offshoot, the “Beast of the East” pep band that plays at hockey and basketball games. What hasn’t changed is the camaraderie that turns more than 100 students into a well-oiled machine each year, delighting sports fans and parade-goers with stirring music and marching drills from Durham to Philadelphia to Dublin.

UNH’s Fia-Chait Irish Dance team trekked to Philadelphia to compete in the seventh annual Intercollegiate Irish Dance Festival at Villanova University in November, placing in several events.

The Wildcat contingent of Lauren Kneeland ’21, Parker Armstrong ’20, Olivia Pitta ’22 and Hannah Flaherty ’23 finished sixth in the 4-hand Reel, competing among a field of 55 groups that made up the largest competition of the event.

Maggie Enderle ’23 finished first in the Freshman Intermediate Treble Reel, while Kerry Dykens was ninth in the Senior Intermediate Treble Reel and Parker Armstrong ’20 captured second in the Senior Advanced Treble Reel.

Twenty-one universities sent teams to the festival.

UNH’s Fia-Chait Irish Dance team trekked to Philadelphia to compete in the seventh annual Intercollegiate Irish Dance Festival at Villanova University in November, placing in several events.

The Wildcat contingent of Lauren Kneeland ’21, Parker Armstrong ’20, Olivia Pitta ’22 and Hannah Flaherty ’23 finished sixth in the 4-hand Reel, competing among a field of 55 groups that made up the largest competition of the event.

Maggie Enderle ’23 finished first in the Freshman Intermediate Treble Reel, while Kerry Dykens was ninth in the Senior Intermediate Treble Reel and Parker Armstrong ’20 captured second in the Senior Advanced Treble Reel.

Twenty-one universities sent teams to the festival.

In November, the UNH men’s ice hockey team made the 3,000-mile trek to Belfast, Ireland, for the fifth annual Friendship Four hockey tournament, splitting games with Northeastern and Princeton. The tournament was established in 2015 as part of the Boston/Belfast Sister City agreement and was formed to help strengthen cultural, economic and academic ties between Northern Ireland and America.

In November, the UNH men’s ice hockey team made the 3,000-mile trek to Belfast, Ireland, for the fifth annual Friendship Four hockey tournament, splitting games with Northeastern and Princeton. The tournament was established in 2015 as part of the Boston/Belfast Sister City agreement and was formed to help strengthen cultural, economic and academic ties between Northern Ireland and America.

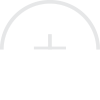

Friday

Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

June 2019

rowing up in rural Vermont with an American father and a Thai mother who met during the Vietnam War, Coffin, an assistant professor of creative writing in the College of Liberal Arts, never felt quite at home. His sense of dislocation only intensified after his parents divorced and his father remarried and started a new family. In fact, it wasn’t until he happened upon a local boxing club in Sitka, Alaska, a year out of Middlebury College, that he finally found a place where he felt like he fit. Encouraged by a local coach, Coffin learned to fight and began participating in the area’s monthly “Roughhouse Friday” competition, a barroom boxing show to determine the best boxer in the Juneau area. A chronicle of the year he won the Roughhouse Friday middleweight title, Coffin’s memoir of the same name pulls no punches in the weighty themes it tackles: love and longing and loss, violence and the nature of masculine identity.

things weren’t looking particularly good for Ruby, a cow in the UNH dairy herd, in December 2018. En route to being milked at the university’s Fairchild Dairy Teaching and Research Center, the 1,200-pound Holstein caught a hoof on a grate, lifted it, and fell 8 feet into the manure trench underneath. Worried that she might drown, farm manager Mark Trabold jumped in with Ruby and managed to get straps beneath her, but it took the combined efforts of the Durham and Madbury Fire Departments and McGregor EMS staff to free the cow, using a large hydraulic mechanical lift to get her out of the pit. Ruby emerged cold and foul-smelling but unharmed, and the grate was quickly chained down to prevent future accidents.

Just two days shy of one year later, Ruby, who was not pregnant when she took her tumble, welcomed a calf. In recognition of the nearly three hours of hard labor that emergency personnel had put into her rescue, students in the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture named the newborn McGregor. First responders were reunited with Ruby and had the chance to meet her calf on Dec. 11.

a digital platform to help educators use experiential education to improve students’ lives and a micro-franchise that delivers vitamin supplementation to people in Haiti were the winners of UNH’s seventh annual NH Social Venture Innovation Challenge (SVIC).

Kendra Bostick ’23G and Bryn Lottig took home the top prize in the student track with Kikori, a digital platform that improves students’ social, emotional and academic outcomes with experiential education activities. First place for the community track went to Haley Burns ’20. Her project, V’ice Haiti, delivers affordable vitamin supplementation to the people who need it most by employing Haitian youth and mothers as micro-franchisees.

Each year, participants develop early-stage concepts for creative, financially viable solutions to society’s most pressing sustainability challenges. Since 2013, the SVIC has seen participation from more than 1,200 contestants and provided over $300,000 in funding and resources to winners.

Place

Need

with

companies

that

do good

ames Smugereski ’19 never planned on working for a nonprofit. He was a business major, with a focus in finance. He interned at one of the country’s largest insurance companies —twice — and thought maybe he’d go into financial planning.

But Smugereski had completed another internship earlier in his college career. One that he sort of fell into after receiving an email from UNH’s Center for Social Innovation and Enterprise announcing the opportunity to earn 16 credits while spending a semester in Boston working for an organization focused on doing good.

Place

Need

with

companies

that

do good

ames Smugereski ’19 never planned on working for a nonprofit. He was a business major, with a focus in finance. He interned at one of the country’s largest insurance companies —twice — and thought maybe he’d go into financial planning.

But Smugereski had completed another internship earlier in his college career. One that he sort of fell into after receiving an email from UNH’s Center for Social Innovation and Enterprise announcing the opportunity to earn 16 credits while spending a semester in Boston working for an organization focused on doing good.

It was Smugereski’s first year of college, and his goal was to get as much experience in as many areas as he could to better prepare him for the future. So, during the fall semester of his sophomore year, the New Hampshire native joined 11 other UNH students in the inaugural cohort of Semester in the City. A new program at UNH, Semester in the City came out of a partnership with Boston’s nonprofit College for Social Innovation to offer undergraduates the chance to spend 15 weeks in Boston interning at leading social change organizations in areas such as community development, education, the environment, health and social justice. In addition to 30 hours of internship work each week, students tackle an intensive evening course on various approaches to social change, Friday seminars and workshops and a special project.

Smugereski was placed with Union Capital Boston, a loyalty program that helps low-income families build resumes of volunteerism and activism by providing social and financial service rewards in exchange for community involvement in schools, health centers and civic programs. A mobile app connects participants to resources and each other to build and strengthen their sense of community. Smugereski was involved with a voter turnout drive and development efforts. He also was responsible for organizing and visualizing data.

“Their whole premise is social capital and the value of community. Making connections creates social capital and can help people get the services they need,” Smugereski says. “To have a business working to make those connections, build those networks — that was all new to me. I hadn’t had any experience with nonprofits before then.”

Smugereski was placed with Union Capital Boston, a loyalty program that helps low-income families build resumes of volunteerism and activism by providing social and financial service rewards in exchange for community involvement in schools, health centers and civic programs. A mobile app connects participants to resources and each other to build and strengthen their sense of community. Smugereski was involved with a voter turnout drive and development efforts. He also was responsible for organizing and visualizing data.

“Their whole premise is social capital and the value of community. Making connections creates social capital and can help people get the services they need,” Smugereski says. “To have a business working to make those connections, build those networks — that was all new to me. I hadn’t had any experience with nonprofits before then.”

“Andrew told me he’d love to have a great job like mine so he could buy his dream car, a Nissan GT-R,” Lee recalls. “I asked him, ‘a GT-R? what’s that?’”

Lee soon found out. He deliberated for less than a day before deciding to buy his son the luxury sports car, which attracted attention wherever Andrew went, and it wasn’t long before Andrew realized his new vehicle could be a vehicle — to raise awareness about and money to support research for HLRCC. When Andrew died on April 21, 2019, nearly four years after his diagnosis, his dream car had become the basis of a nonprofit organization, Driven To Cure (DTC), that has raised more than $600,000 for research on HLRCC and other rare kidney cancers and become a source of information about the disease for individuals and families.

“When Dawn Cockrum reached out to me, one of the first things she said was, ‘any time you search online for HLRCC, the first thing that comes up is Driven To Cure,’” Lee explains.

Photography by Neil van Niekerk

e all have priorities and dreams, but it’s where these intersect that life lessons are forged. It took Donna Schleinkofer Lynne ’74 all of one semester, not even that long, really, to learn a life lesson she’d never forget: Sometimes a priority outweighs a dream.

A three-sport high school athlete and academic standout from New Jersey, Lynne came to UNH with aspirations to play field hockey and tennis while double-majoring in economics and political science. The only hitch was that she’d have to work her way through college, as family support wouldn’t come close to covering her expenses.

Photography by Neil van Niekerk

e all have priorities and dreams, but it’s where these intersect that life lessons are forged. It took Donna Schleinkofer Lynne ’74 all of one semester, not even that long, really, to learn a life lesson she’d never forget: Sometimes a priority outweighs a dream.

A three-sport high school athlete and academic standout from New Jersey, Lynne came to UNH with aspirations to play field hockey and tennis while double-majoring in economics and political science. The only hitch was that she’d have to work her way through college, as family support wouldn’t come close to covering her expenses.

The choice was as painful as it was inevitable. Although she would continue to attend games as a spectator, Lynne said goodbye to UNH field hockey as a player. Instead, she focused on her studies, loading up on extra courses so she could graduate a semester early — with high honors. Along the way, she met faculty mentors who would change her life.

In political scientist David Larsen, Lynne found a mentor who catalyzed her activist side — she was, after all, “a child of the ’60s” — and gave her a job as researcher with the New Hampshire Council on World Affairs. The Council’s mission was to bring greater awareness of international politics and affairs into traditional New Hampshire classrooms, where, Lynne recalls, “international studies weren’t reflective of the political turmoil in the world.” In business professor Nina Rosoff, Lynne discovered “the first woman I ever met who wasn’t teaching children or subjects like art or literature, somebody about whom I remember thinking, ‘She’s the kind of woman I want to be.’”

For Lynne, this would ultimately mean attaining a position from which she would be able to help others, starting with careers in government service and healthcare leadership. It also would mean circling back to her alma mater, where she would establish endowments to support female student-athletes, in the hope that they wouldn’t have to make the hard choice that she had.

If your class is not represented here, please send news to your class secretary (see page74) or submit directly to Class Notes Editor, UNH Magazine, 15 Strafford Ave., Durham, NH 03824. The deadline for the next issue is April 15.

9 Rickey Drive, Maynard, MA 01754; bryantnab@yahoo.com; (978) 501-0334

UNH Magazine, 15 Strafford Ave, Durham, NH 03824 classnotes.editor@unh.edu

For more than 50 years, I have truly enjoyed participating in and making a positive impact on diversity at UNH — a never-ending journey.

I came to UNH in 1969 on a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. academic scholarship and graduated in 1973 as the first black American to earn a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering at the university. I also lettered in varsity basketball. After graduation, I became an adviser to the mechanical engineering department, served on the UNH Foundation board of directors, worked closely with the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs (OMSA) and maintained a close relationship with the athletic department.

In 2008, I was honored to be inducted into the UNH Diversity Hall of Fame, which became inactive a few years later due to a lack of support and funding. Believing that more black alumni deserved recognition, I worked with former OMSA director Sean McGhee to plan a UNH Pioneer Black Alumni, Family and Friends Reunion and Diversity Hall of Fame induction ceremony. In 2015 and 2017, the events were primarily self-funded, with UNH providing support for students to attend the dinner.

alumni@unh.edu | (603) 862-2040

Naples, FL

here’s a scene in the 2019 film “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” in which the main character, a young writer who has been assigned to write an article about children’s television icon Fred Rogers, spends the night at Rogers’ home. When he comes down the next morning, he finds Rogers, played by Tom Hanks, and his wife Joanne, played by Maryann Plunkett ’76, playing a rousing duet on two grand pianos.

The writer expresses acute awkwardness for intruding on the Rogers’ private time, but Joanne puts him at ease, serenely assuring him that their new friendship means the world to her husband. It’s a brief scene and one of just two featuring Joanne, but her words are exactly what the writer needs to hear to move forward in his relationship with his subject (and his own life).

t could seem intimidating to grow up with a father whose legacy is essentially as large as the highest mountain peak on Earth. Instead, Norbu Tenzing Norgay ’86 has fully embraced it.

Tenzing’s father, Tenzing Norgay, was a Sherpa who, along with Sir Edmund Hillary, completed the first successful summit of Mt. Everest in 1953, and Tenzing grew up in the foothills of the Himalayas “deeply familiar” with his father’s achievement.

Rather than shy away from that, though, Tenzing has made it his life’s work to protect both the mountain that made his father famous and the people who call the area home. As vice president of the American Himalayan Foundation, Tenzing helps to ensure citizens of the region have access to such necessities as education and medical facilities.

“The older I get, the more I appreciate my father’s legacy and the impact he had on me,” Tenzing says. “Each day I wake up feeling my father’s presence to some degree.”

Tenzing has spent virtually his entire life in the mountains. He grew up in Darjeeling, India, with “an unobstructed 180-degree view of mountains” from his family home. He recalls spending many holiday seasons in the mountains of Bhutan, Nepal and Sikkim, and after briefly attending Manhattanville College in Purchase, New York, he transferred to UNH and took advantage of the natural beauty of the Granite State, as well.

t didn’t matter that attorney Bradley Olson ’94JD, partner in Barnes & Thornburg LLP, had been knighted by the King of Sweden and awarded the chivalric rank of Commander — when you’re arguing a case in front of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, you’re just another lawyer.

Olson, an expert in patent law and intellectual property management, was representing an optical glass fiber manufacturer that had been sued by a competitor in the International Trade Commission for patent infringement. The case, which was argued in December 2019, was worth millions of dollars. Ultimately, the court ruled in Olson’s favor.

“You’re close enough to just about reach out and touch one another,” Olson says, recalling the courtroom scene while relaxing for a moment in his Washington, D.C., office. “It’s just three judges asking me all kinds of questions. And I had to be fast with answers, because the judges don’t care if they’re making me look bad.”

Built in 1919, Huddleston Hall hosted plenty of interesting characters in its first century on the Durham campus — from the countless students who took their meals there during the decades it served as UNH’s first dining hall to the alumni couples who have returned to celebrate their weddings with Wildcat friends. The historic building’s first guests of its hundred and first year, however, were of a different variety altogether: 17 soldiers, two chariots and a horse — full-sized museum replicas of sculptures from China’s famed Terracotta Army, which were on display in the Huddleston Hall Ballroom Jan. 22–30.

One of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the modern era, the Terracotta Army was discovered in 1974 by farmers in Shaanxi, China: a collection of some 8,800 lifesized figures of warriors, chariots and horses that had been interred with Quin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, some two centuries earlier. Created to protect the emperor’s tomb and serve as his army in the afterlife, the terracotta figures are remarkably realistic, with unique facial features and expressions. The exhibit, sponsored by the College of Liberal Arts and the Confucius Institute, took two months to ship from China to UNH. UNH students, area schools and curious locals made the most of the figures’ visit, enjoying lectures and workshops and the rare opportunity to experience a piece of ancient history for themselves.

Built in 1919, Huddleston Hall hosted plenty of interesting characters in its first century on the Durham campus — from the countless students who took their meals there during the decades it served as UNH’s first dining hall to the alumni couples who have returned to celebrate their weddings with Wildcat friends. The historic building’s first guests of its hundred and first year, however, were of a different variety altogether: 17 soldiers, two chariots and a horse — full-sized museum replicas of sculptures from China’s famed Terracotta Army, which were on display in the Huddleston Hall Ballroom Jan. 22–30.

One of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the modern era, the Terracotta Army was discovered in 1974 by farmers in Shaanxi, China: a collection of some 8,800 lifesized figures of warriors, chariots and horses that had been interred with Quin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, some two centuries earlier. Created to protect the emperor’s tomb and serve as his army in the afterlife, the terracotta figures are remarkably realistic, with unique facial features and expressions. The exhibit, sponsored by the College of Liberal Arts and the Confucius Institute, took two months to ship from China to UNH. UNH students, area schools and curious locals made the most of the figures’ visit, enjoying lectures and workshops and the rare opportunity to experience a piece of ancient history for themselves.