Nature

raising greatness

Nature

lessons while

raising greatness

ife as a professional basketball player can be a nomadic adventure. Few are as well-acquainted with that experience as New Hampshire native Duncan Robinson, whose circuitous path to the NBA once included a winter stretch shuttling back-and-forth between the conflicting climates of South Dakota and South Beach.

Robinson has since established himself as a starter on a Miami Heat team that went to the NBA Finals last season, but he still faces the mental and physical grind of living out of a suitcase for days or weeks at a time, bouncing from city to city on overnight flights and maintaining a schedule on which stability and regularity are in short supply.

But through it all, there is one thing Robinson can lean on to ground him before every game, to provide a sense of familiarity and comfort in the chaos.

A string of emojis.

No matter what city he finds himself in or what time the game tips off, Robinson is greeted with a pregame text from his mother, Elisabeth Robinson ’80 ’95G, who is as generous with her use of symbols as she is with her support.

“She always texts me the same thing before every single game: She’ll say, ‘BE YOU,’ in all caps,” Duncan says. “And she loves emojis — and not just a couple of them. She’ll send like seven basketball emojis, seven heat emojis, then a bunch of stars. She’ll just line them all up together.”

Elisabeth is just as reliable as Duncan’s shooting stroke, too. Because of the extensive pregame preparation required on a nightly basis, Duncan has to stash his phone hours before tip-off — but mom always beats the buzzer.

And the fact that the single most influential person throughout his winding basketball journey is still his biggest source of support is a reminder of how he was able to complete the journey in the first place.

“She’s never missed one — never,” Duncan says. “I could not tell you a game in my career where she didn’t text me beforehand.”

For Elisabeth, it’s a way to stay connected as Duncan chases his basketball dreams. Her role evolved over the years from coach — she was at the helm of Duncan’s third-grade team — to career confidante and proud mom.

“It wasn’t always an easy road,” Elisabeth says. “He had a lot of doubters in the past, but he just kept getting up and going to the gym.”

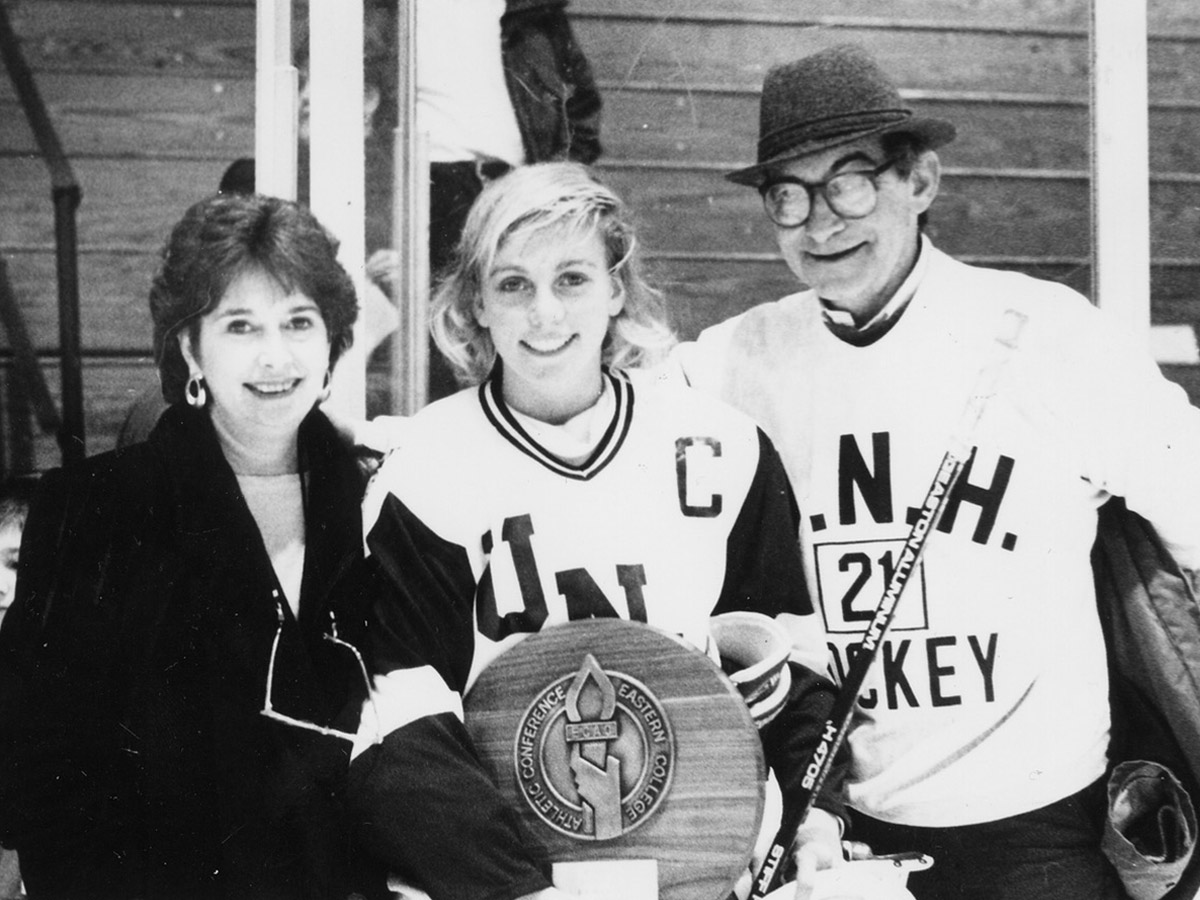

All three were athletes in their own right — Hughes starred in soccer and hockey at UNH, while Robinson joined the crew team and Shiffrin passed up an opportunity to ski at UNH to pursue a nursing degree — and all went from leading the caravan to leading cheers for children who have reached the pinnacle of their respective sports.

The paths and the circumstances along the way could not have been more different. Robinson had to fight to get noticed at every stage of his career, while the Hughes boys carried the pedigree of sought-after prospects and both went in the top 10 of their respective NHL drafts and Shiffrin rose to the global peak of an individual sport.

The roles each mom played were unique, too. Robinson was the philosophical advisor and self-proclaimed “ethical police,” Hughes the elite athlete example and Shiffrin the omnipresent hands-on coach. But all instilled tireless work ethics and offered steadfast support from day one. And though the journeys were disparate, the results were ultimately the same: children who have achieved the highest level of success in their given sports.

“For me it was all worth it because I just believe that playing sports is good for you,” Ellen Hughes says. “I love that they’re part of a team, I love that they’ve found their own passion. It’s a little bit surreal, but I’m just super proud of them and what they’ve been able to accomplish.”

Elisabeth wasn’t just her team’s leading scorer in that contest; she was responsible for every single point her squad posted.

All four of them.

Elisabeth grew up in Chicago where hockey was king and didn’t explore basketball until she moved to Massachusetts to attend the Berkshire School. The school was just starting a basketball program during her sophomore year, and she did indeed account for both of her squad’s opening-night buckets in what she recalls as a 64-4 trouncing.

She quickly developed a fondness for the sport, though, and went on to play at the University of Redlands in California. But she didn’t find happiness there and sought to transfer, ultimately choosing UNH.

In Durham, she tried out for basketball but rust from a long layoff led to her missing the cut for the team. She opted to give crew a shot instead, though, and rowed for several years. She stayed in New Hampshire after graduation and met Duncan’s father, Jeffery, an accomplished basketball player who had won a high school championship in Maine. The couple had three children, with Duncan the youngest.

Elisabeth impressed the importance of physical activity upon her children early, and concerned about society’s increasing reliance on electronics, she subbed in hiking, camping and sports for television. Basketball was always the favorite, though, and when winter came around and it grew too cold to play outdoors, she moved all of the furniture aside in their New Castle, New Hampshire, living room and set up a mini basketball court.

Elisabeth coached Duncan’s team in third grade, purchasing plastic safety glasses for each player and placing tape on the lower half of the lenses to force them all to learn how to dribble with their head up. But for most of Duncan’s youth she spent more time enforcing good sportsmanship than focusing on Xs and Os.

She recalls watching a player on Duncan’s older brother’s team who would always remove his shoes prior to the end of the game and how much it irritated her because it illustrated a lack of respect as a teammate.

Duncan pulled the same maneuver toward the end of a blowout win in fifth grade. It … didn’t go over well.

“I went right up to him after and said, ‘Don’t you ever let me see that again,’” Elisabeth says. “To me it was about the ethics of being a good team player.”

When college rolled around, Duncan didn’t garner extensive recruitment attention from Division I programs. Instead, he enrolled at Division III Williams College in Massachusetts, where he helped the Ephs reach the D-III national championship game. But when his coach left for a Division I coaching job, Duncan began exploring D-I transfer opportunities himself. The University of Michigan rolled out the red carpet for a visit by the Robinsons, who were chaperoned by such an attentive crowd they had to steal a few minutes in the hotel elevator just to have a private conversation.

With her son facing one of the biggest decisions of his life, Elisabeth referenced … her refrigerator.

“I had a saying on our fridge: ‘do one thing every day that scares you,’” Elisabeth says of her fodder for the elevator chat. “By the end of the visit he said, ‘I don’t think I can say no to this.’”

It certainly turned out to be the right call. As a senior in 2018, Robinson was part of a Michigan team that reached the Division I national championship game, and despite playing just three seasons he finished his career fourth on Michigan’s all-time list for 3-pointers made with 237.

As had been the case throughout his career, though, the next step didn’t come easy — and featured yet another influential heart-to-heart with his mother. Duncan wasn’t selected in the 2018 NBA draft, leaving him to decide between two paths: sign with an agent in the U.S. and fight to get noticed by an NBA team, or sign with agent overseas and pursue a career there.

If Duncan was struggling with the decision, his mother certainly wasn’t.

“She said, ‘What are we even talking about here? What have you done your whole career? Bet on yourself, push the chips to the middle and go for your dream.’ She helped it come into plain sight,” Duncan says.

Duncan indeed went for his dream. He caught the eye of the Miami Heat, who invited him to the NBA Summer League in 2018 and rewarded his strong play there with a two-way contract with the Heat and their developmental league affiliate, the Sioux Falls Skyforce. That meant an occasional 1,826-mile commute as Duncan was shuttled between the squads.

“I just welled up. I couldn’t even talk,” Elisabeth says. “I was just in stunned mom mode, just watching and smiling and enjoying it. I was so incredibly proud.”

His impressive play during that rookie year earned him a fully guaranteed contract with the Heat for the 2019-20 season, and despite a bizarre season that included a three-month pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Duncan emerged as a starter and the Heat reached the NBA Finals, losing in six games to LeBron James and the Los Angeles Lakers.

Duncan is the only player ever to compete in the championship round at the Division III, Division I and NBA levels.

“I’m just so happy for him,” Elisabeth says. “He’s always had such a good ability to do the little things. He’s always thinking, ‘If I do the little things, big things will happen, and big doors will open.’ That work ethic is why he’s so successful.”

“Particularly at this level, when so many people are critical and people are paid to be critics, she is just relentlessly positive,” Duncan says. “I could miss every single shot and she would say my energy was good, or that I played good defense. For her, it’s never been about what level I am playing at, it’s all about her son doing what he loves and being happy and experiencing success.”

She just didn’t know what she was going to do with the last six days.

Hughes came to UNH as a scholarship soccer player but had spent her childhood in Dallas, Texas, playing hockey “with the boys,” so she was confident she’d carve out a roster spot — even though she was trying to walk on to one of the most successful hockey programs in the country.

“Because I was late, I remember coach McCurdy saying, ‘I’ll give you a week to get in shape.’ After the first practice he said, ‘What size skates do you need?’” Hughes recalls.

That, however, also opened the door to her next career as a reporter in sports television, which is how she met her husband, Jim, a former player at Providence College who was coaching collegiate hockey and would go on to be a longtime coach and executive in the NHL.

Quinn was drafted No. 7 overall by the NHL’s Vancouver Canucks in 2018, and his kid brother one-upped him a year later when he was taken first overall by the New Jersey Devils, becoming just the eighth American-born player to ever go No. 1 in the NHL Draft.

That path may have seemed preordained, but Ellen and Jim never pressured the boys to play hockey. Jack was quoted in the Detroit News as saying, “they don’t push anything on us.”

But they did encourage them to always be playing … something.

The boys certainly took to the early exposure. A Boston.com headline in June 2019 referred to Jack as “Barry Sanders on skates,” comparing his skill and agility favorably to perhaps the shiftiest running back in NFL history. In the same story Jack credits his mother for teaching him to skate.

Despite the star athlete lineage, though, Ellen and Jim eschewed any hyper-focused private training for their children in favor of free-flowing experience gained on frozen ponds in New England and Canada.

The boys skated all winter when they lived in New Hampshire and took advantage of municipal rinks in Toronto when Jim was there with the NHL’s Maple Leafs. Ellen remembers filling her Suburban with a carload of kids and heading to the outdoor rinks in Toronto on Friday nights, where they would play from early evening until the lights went out — fueled by hot chocolate and pizza delivered by Ellen.

“They were constantly on outdoor ice,” Ellen said of the boys. “We were really into the lack of structure — it was a free, creative, fun activity.”

Oh, but there were still plenty of structured games. And with Jim often traveling in his roles with NHL clubs, the responsibility to get all three boys where they needed to be fell largely on Ellen, who left her job after 15 years in television to be a full-time hockey mom.

In an interview with Canadian media outlet Sportsnet, Jim referred to Ellen as the “master planner.”

“One thing Jim and I did instill in them was that competitiveness, because we’re really competitive ourselves — we played everything with the kids,” Ellen says. “We always encouraged them to be the hardest-working kids out there, and to be great teammates.”

Thanks to that foundation, the boys blossomed. Ellen credits the USA Hockey National Team Development Program (NTDP) for really fueling that development in Quinn and Jack, and Luke is now taking advantage of the same training as he pursues his own professional hockey dreams (he’s a projected top-10 pick in the 2021 NHL draft). With Ellen and Jim’s hockey genes and the prospect of having three children in the NHL at the same time, it’s no surprise the Hughes family has been essentially anointed hockey royalty. They’ve been referred to by the NTDP website as the “royal hockey family” and dubbed “America’s future first family of hockey” by ESPN in 2018.

Despite all of the accolades, though, Ellen is most proud that her children were always receptive to their focus on character, that being a good teammate is more important than anything else — even if it’s just being a good teammate to each other.

“We really tried to instill in them the idea of being a great person in society first,” Ellen says. “If there’s one thing I’m most proud of, it’s what good friends my three boys are to each other, because I think that will take them through life. They are great brothers and great friends, and they look after each other.”

At the time, students enrolled in the nursing program weren’t allowed to participate in athletics, Eileen told the New Yorker in a 2017 story, prompting her to press pause on her sport of choice for four years in order to chase the career she desired.

So when her daughter, Mikaela, had the opportunity to fulfill her own destiny on the slopes without any such sacrifices, it’s not a stretch to say Eileen helped her attack the quest with a singular focus.

Singular, sometimes, as in “one wheel.”

A 2018 Time Magazine article notes that Eileen was so intent on developing her daughter’s athleticism that she purchased unicycles for a young Mikaela and her brother, Taylor, to enhance balance and coordination.

“We were a very strange family,” Mikaela playfully quipped to the publication.

Strange? Perhaps. But the approach was undoubtedly successful. With her mother as her de-facto coach throughout her career, Mikaela Shiffrin has gone on to become one of the most decorated skiers in American history, with two Olympic gold medals and three World Championships under her belt at the age of 25. She became the first woman to win three consecutive slalom world titles in 78 years when she captured the crown in 2017 and has won four World Cup slalom championships.

And Eileen has been there every step of the way, evolving from supportive mother to full-time coach. That evolution started early and occasionally involved blurred lines between the two roles; according to the New Yorker, Eileen and husband, Jeff, often “dragged Mikaela around the living room and the driveway on skis when she was a toddler” and taught her at such a rapid pace she quickly outclassed her kindergarten counterparts. Instead, she skied with Eileen, up to and including her time as a high-schooler at Burke Mountain Academy in Vermont, where Eileen maintained a condo minutes from campus so she could join her daughter for regular runs on the slopes.

Even Mikaela has had to occasionally pause to make sure she was in the right frame of mind to receive certain critiques.

“If she’s talking to me as my coach and I’m listening to her as her daughter, that’s one of the most heartbreaking, painful things,” Mikaela told Time. “Those conversations can be terrible.”

Mikaela admitted in the same interview, though, that she’s developed a better radar for discerning which hat Eileen is wearing when she’s delivering information, and that that realization has been “awesome.”

So, too, have been the results. And despite perceptions in certain corners and the occasional need to reset her receptors, Mikaela has long embraced the comfort that comes with having her mother with her. She referred to Eileen in the New Yorker as having “always been my best friend.”

The pair recently had to lean on that relationship even more strongly in the wake of two devastating family tragedies in less than a year, one of which prompted Eileen to step away from coaching Mikaela and another that led to her return.

When Eileen’s mother, Pauline Condron, died in October 2019, Eileen opted to take a break from coaching, according to an article in the New York Times. Then, on Feb. 2, 2020, Eileen and Mikaela were rocked by the news that Jeff had unexpectedly died as the result of an accident at home, prompting Mikaela to take some time away from skiing to mourn her father.

When she returned, Eileen was once again by her side. And that will no doubt be the arrangement for the foreseeable future, with both of Eileen’s roles — supportive mother, ever-present coach — perhaps more important now than ever.

Despite the personal grief and the raging COVID-19 pandemic — both of which altered her training routine — Mikaela fought to make her return to the slopes in late 2020 and won a World Cup giant slalom race in Courchevel, France, in mid-December, her first victory since just before Jeff’s passing.

As an emotional Mikaela tried to compose herself for a post-race television interview, Eileen was the first person to greet her with a hug.

That’s perhaps the biggest adjustment for the moms these days — as their children ascend to new levels of success, the practices and games are no longer a simple car ride away. Staying in close contact now is characterized by chains of emojis and phone calls on the run. Finding a seat on the sidelines often requires lengthy cross-country — or, in Shiffrin’s case, in particular, international — flights.

“I think being in the game and having a husband that worked in the game, I see how hard it is to make it to the NHL and have success and have a sustained career,” Ellen Hughes says. “So, we are still new to this today — we’re still finding our way.”

“One of my favorite things about my mom is that even when I was playing in empty gyms in high school and she was driving three, four or sometimes five hours one way to watch me play 10 minutes, or sometimes not even check in,” Duncan Robinson says. “If I had a good game in one of those games, she was just as excited for me then as is she is when I have a good game today.”