Timothy Sheahan ’99

Ryan Dion ’04

Ruth Gannon ’67

Ed Friedlander Jr. ’88

Bryan Lyons ’91

ne month after we began one of the most unusual semesters in UNH history, I shared an update with the university community, noting that, “We are still here.”

As this issue of UNH Magazine goes online, our campuses are not only open, but they are achieving remarkable success in scholarship, research and philanthropy. Last summer, there were many who doubted whether UNH had the expertise, capacity and shared sense of community it would take to open our campuses safely—and to keep them open. Some predicted that COVID-19 cases would spike within the first few weeks, and that we would have to send everyone home.

We are not out of the woods yet, by any stretch, and we must remain vigilant. However, we are fast approaching the beginning of Thanksgiving break, when students will return home to complete the fall semester, as planned. I am extremely proud and grateful to our entire Wildcat family for getting us this far.

Kristin Waterfield Duisberg

Class Notes Editor

Allison Battles ’02

Feature Writers

Todd Balf ’83

Keith Testa

Contributing and Staff Writers

Kim Billings ’81

Ali Goldstein

Lily Greenberg ’21G

Rebecca Irelan

Allen Lessels ’76

Catherine Meyer

Michelle Morrissey ’97

Beth Potier

Daniel P. Smith

Jody Record ’95

Sarah Schaier

Contributing and Staff Photographers

Anna Burns ’20

Merrily Cassidy

Jeremy Gasowski

Greg Greene

Team Hoyt

Brian Samuels Photography

Megan May

Scott Ripley

Matt Troisi ‘22

◆

Editorial Office

15 Strafford Ave., Durham, NH 03824

alumni.editor@unh.edu

Publication Board of Directors

James W. Dean Jr.

President, University of New Hampshire

Debbie Dutton

Vice President, Advancement

Mica Stark ’96

Associate Vice President,

Communications and Public Affairs

Susan Entz ’08G

Associate Vice President, Alumni Association

Heidi Dufour Ames ’02

President, UNH Alumni Association

◆

◆

UNH Magazine is published three times a year by the University of New Hampshire, Office of University Communications and Public Affairs and the Office of the President.

© 2020, University of New Hampshire. Readers may send letters, news items and email address changes to alumni.editor@unh.edu.

efore I found my calling as a writer and editor, I spent nearly five years working at a global investment bank in New York City. While prestigious, the position was a terrible fit for me — I struggled daily to care about my work, and even when I stepped off the banking “fast track” (to the horror of my peers) to work instead in communications, few and far between were the stories I told about the bank’s activities and achievements that truly resonated with me.

Almost three decades later, I had occasion to dust off my knowledge of complex global financial institutions to write about Anne Finucane ’74, vice chairman of Bank of America and chairman of the board of Bank of America Europe. Anne is one of the most powerful women in business, and I was more than a little intimidated. But when I interviewed her over the summer, I came away struck by the depth of the bank’s commitment to using its size and its position to do good in the world — as well as Anne’s own dedication to the same causes, and her surprising sense of humor. It may well be that the banking world has changed significantly since I left it; it may also be that I worked for the wrong institution. I hope you enjoy reading about her and come away as convinced as I am that there isn’t a more deserving recipient of the university’s Social Innovator of the Year Award, an honor she will receive Dec. 1.

You have been involved in student affairs at other universities, most recently Howard University in Washington, D.C. Why UNH?

With all the opportunities that were made available to me, UNH just felt right. I liked that the position was a senior vice provost. We are all here to support the university’s academic mission. Working with the provost and other educational leaders allows me to better serve students both in and outside the classroom.

What is the most valuable thing you have learned during your years working with students?

Students can truly make your work life more comfortable if you genuinely listen to them. When we listen to students, they tell us what they need to be successful, and when they know you are listening and are working on programs and services to make their lives better on campus, they will give you grace. And when possible, they will assist. With resources, I love what I do.

“There’s no practicing this,” says Thomas, who serves as the lab’s scientific director. “You can’t say, ‘send me 4,000 samples so we can try this out.’”

single grant in the College of Health and Human Services (CHHS) for $23.6 million. More than 200 awards at the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans and Space (EOS), UNH’s largest research center, totaling $60.2 million. Fiscal year 2020 was a record-breaking year for competitive research funding at UNH, which closed the books on June 30 with $129,815,354 in new grants and contracts. It’s the most external research funding the university has received in a single year, supporting UNH projects that range from improving preschool education in New Hampshire to bringing sustainable seafood to the table.

he Emancipation Proclamation decreed that on Jan. 1, 1863, all “persons held as slaves within any State” in the United States would be “forever free.” But it would be two and a half years before the 250,000 Black men and women living in Texas got the news. That’s when, on June 19, 1865, Union Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston and announced that the Civil War was over, and with it, the end of slavery, officially enacted with the adoption of the 13th Amendment.

“Recognizing this day reflects our deep commitment to and support of our multicultural communities across our campuses,” UNH President James Dean said in announcing the board’s decision. “The recognition of this important day in our collective history is just one small piece of the work we must do as an institution to address racism and promote diversity, equity and inclusion.”

f you’ve enjoyed a meal at Tuscan Kitchen or count on NOBL cold brew coffee to get you through your workday, you can give at least some credit to UNH’s Paul J. Holloway Prize Competition.

The annual event recognizes students who conceptualize, develop and pitch compelling proposals to bring products to market and awards students thousands of dollars in cash and prizes every year. The successful Tuscan Kitchen chain of restaurants launched by Joe Faro ’91 was born of a Holloway competition idea, as was NOBL, the Holloway brainchild of Connor Roelke ’14. This year’s first place winner, Kikori, is a software platform that allows K-12 educators to incorporate more learning-by-doing activities into their classroom experiences. Developed by graduate students Kendra Bostick, Bryn Lottig, Bhavya Wadhwa and Gayathri Venkatasrinivasan, Kikori is particularly timely as schools around the country adjust to the new normal of remote learning.

nnovation, leadership, community service and entrepreneurship are just a few of the skills and experiences that the newest members of the UNH Foundation board of directors possess. Their UNH friends might also recognize them as a swimmer, a geology major, a lacrosse player, a student body president, two psychology majors and a Sigma Beta brother.

These six new members share a common passion for their alma mater, while representing an impressive array of personal experiences and professional expertise, says Debbie Dutton, president of the UNH Foundation and vice president of university advancement.

It’s a piece of advice often given to fiction writers to help ensure that their stories have power and authenticity. This summer, Charlotte Gross ’21G, a master’s student in UNH’s graduate writing program, took that advice a little more literally than perhaps she had expected to when she found herself on the frontlines of one of the most catastrophic fire seasons in U.S. history.

o better reflect its position as a partnership among UNH’s Sustainability Institute, the Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics and the Carsey School of Public Policy, in August, the UNH Center for Social Innovation and Enterprise relaunched as the Changemaker Collaborative. The change, UNH Deputy Chief Sustainability Officer Fiona Wilson says, runs deeper than a new name. “With our partners, we have collectively refined and clarified who we are and what we do in order to help us better reflect our mission and vision, and more effectively communicate with students, faculty, staff and with our partners in the community,” she explains.

nce again UNH has shown its true colors — blue and white and green — after being named one of the most sustainable schools in the country by two of the top organizations that track higher education institutions’ commitment to sustainability.

UNH has previously been recognized for its sustainability efforts by the Chronicle of Higher Education Top College for Sustainability. In 2017, the UNH Durham campus became one of the few institutions of higher education to earn a STARS Platinum rating from the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE).

or the last half century, scientists and students have kept their fingers on the pulse of Great Bay and coastal New Hampshire thanks to a UNH outpost tucked along the shores of the state’s largest estuary.

The Jackson Estuarine Laboratory, located on Great Bay’s Adams Point, celebrates its 50th anniversary this year — that’s five decades of research on microbes, oysters, seaweeds, eelgrass, lobsters, horseshoe crabs, water quality and much more. A lot has changed since 1970, but one thing has remained steadfast: Jackson Lab’s commitment to advancing the understanding and preservation of estuarine, coastal and marine ecosystems.

f you want to understand how a species will survive or fail, one of the things you need to know is whether its population is mating at top capacity. A new study from UNH has discovered a better way to count sperm in lobster that could help researchers of any animal species understand this key aspect of survival.

UNH scientists looking to better understand how climate change may alter lobster reproduction are measuring the amount of DNA contained within the lobster’s spermatophore — the mass of sperm a male lobster transfers to a female during mating. The new technique, which is described in an article recently published in the Journal of Crustacean Biology, is an important alternative to existing methods, which are both costly and time-consuming.

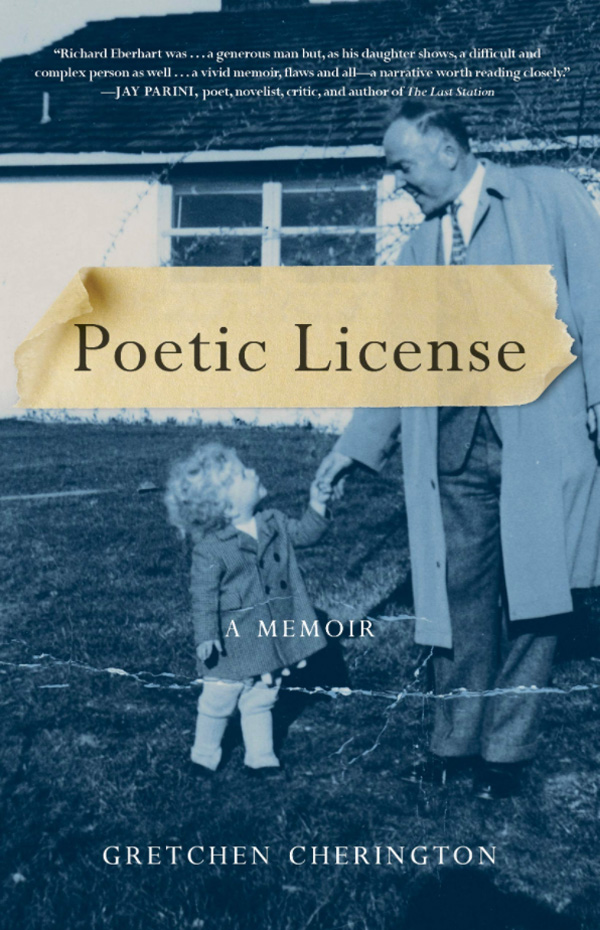

She Writes Press

August 2020

n the surface, Gretchen Cherington’s childhood was the stuff of idyll. Growing up in Hanover, New Hampshire, she’d regularly come home from school to find literary luminaries such as Robert Frost, Robert Lowell, Allen Ginsberg and Anne Sexton visiting with her equally famous father, Dartmouth professor and New Hampshire poet laureate Richard Eberhart. She spent summers at Undercliff, a Maine cottage at the edge of Penobscot Bay, where her father piloted a boat called Reve and she and her brother Dikkon annually reenacted their parents’ love story to an indulgent beachfront crowd. There were also two years in Washington, D.C., while her father served as the poet laureate of the United States, and a year in Lausanne, Switzerland, where a 16-year-old Cherington traveled to study and perfect her French.

for

Better

s vice chair of Bank of America, she’s one of the most powerful women in the business world. But when Anne Finucane ’74 was a student at UNH, she thought she’d be an artist — a path she forswore after she took a painting course at the Paul Creative Arts Center and concluded that she wasn’t the top student in the class. “I’m competitive,” Finucane recalls, “and I realized I was never going to be as good as the most talented art students there, no matter how hard I tried, so what was the point?”

The point, arguably, was that her destiny lay elsewhere: in a string of job opportunities that she embraced, excelled at, and inexorably parlayed into a leadership role in the rarefied realm of global finance. Finucane’s own explanation, however, is quite different.

arnelle Bosquet-Fleurival’s Monday begins with the shrill sound of her alarm at 6 a.m., a painfully early start given that her first task is to sift through reports detailing the reality of supervising residence halls during a weekend on a college campus.

There are documents to file with administration and incidents to review, often beginning with minor infractions but commonly including violations centered on racial and cultural insensitivity. As an assistant director of residence life supervising four hall directors — a position she previously held on campus for several years — her experience encountering reports of racial or homophobic slurs scribbled on white boards or sexually offensive messages scattered throughout hallways is certainly not unique among fellow staffers.

Her experience differs greatly from the vast majority of her coworkers in one significant way, though.

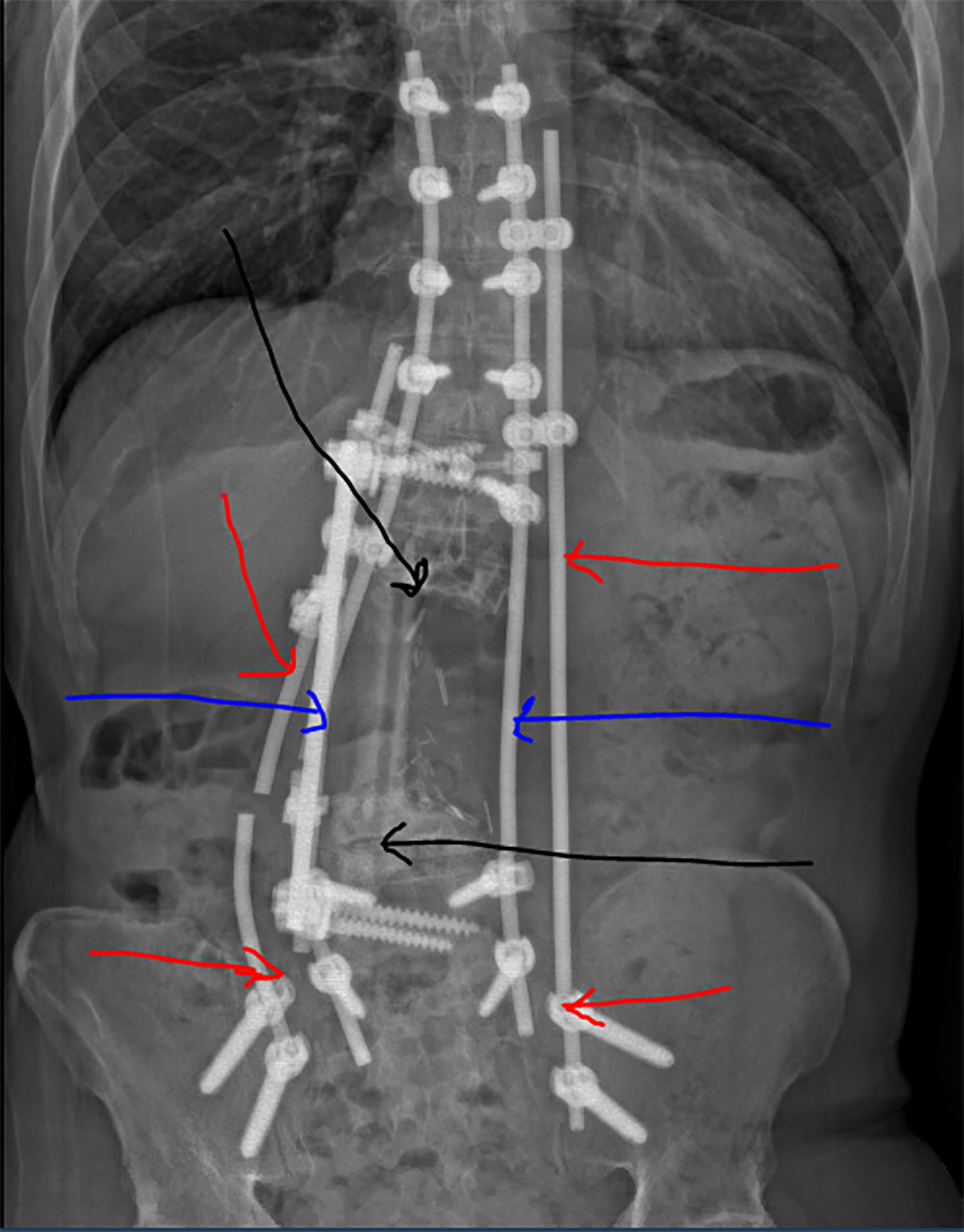

he day I was diagnosed with a rare spine cancer, I knew I had a problem, just not that problem. For the better part of a year, I had stripped away movements — from gym core routines I didn’t much like anyway to things I did, like raking a yard of warm compost into old winter soil. I told others that when I could no longer ride a bike, a lifetime passion, I would see my doctor to confirm what I already knew: I had a disk problem. Every 50-year-old I knew had some sort of lower-back ailment they didn’t do anything about. We were a league, stoic and proudly inattentive. In July of 2014, I couldn’t sleep or stand without having disabling waves of nerve pain running the course of my legs. I was off the bike. I made the appointment.

I knew they had seen something bad the moment the imaging techs slid me out from the white MRI silo. They had seemed distracted when I arrived. They weren’t now. Did I need more warm blankets? asked one. Something to drink? asked another. Is somebody coming to bring you home? They led me upstairs, where the head spine surgeon, a genial Irishman, showed me the image of a tumor type he had heard of but never seen in a patient. It was a softball-size mass affixed to my lower spine, billowing out north by northwest, distinguished by its lobed shape, which looked to my uneducated eye like the human brain. Dr. Terence Doorly stressed that nothing about this thing inside me — slow-growing, exceedingly rare, originating from leftover prenatal spinal cord cells — was run-of-the-mill.

Don’t see a column for your class? Please send news to your class secretary, listed at the end of the class columns, or submit directly to classnotes.editor@unh.edu. The deadline for the next issue is January 15.

Don’t see a column for your class? Please send news to your class secretary, listed at the end of the class columns, or submit directly to classnotes.editor@unh.edu. The deadline for the next issue is January 15.

We asked, you answered! Edwin “Duke” Kline ’71 responded almost immediately to the archive photo featured in this space in spring/summer magazine for which we were seeking additional information, as follows: “I’m very confident that the photo was taken in the fall of 1968. The Black fellow is my good friend and former UNH roommate Carl “CP” Patterson ’71. The others all look familiar but I can’t place their names.” Shortly after we heard from Kline, Patterson himself wrote in: “I am the young African American Wildcat on the bottom row, second from the left. The classmate standing next to me — third from the left — is Jim Raymond. I’m not positive, but I think this could have been taken at the freshman beanie pole climb.”

Thanks, Edwin and Carl! Now, how about the above photo, Wildcat family? Please drop us a line at alumni.editor@unh.edu if you recognize these two young women. Bonus points if you can tell us the year and/or the location of this lab!

Ruth Payne Moore has been living at Brooksby Village in Peabody, MA ,for the past 20 years. Ruth’s husband, William “Mickey” B. Moore Jr. ’41 passed away six years ago. While at UNH, Ruth and Mickey were active members of the Outing Club, spending weekends and holidays skiing and hiking. Ruth still reminisces about the good times on club trips to the White Mountains with classmates. During their married life Ruth and Mickey settled in Peabody then Topsfield before moving to Brooksby Village. Until recently, Ruth continued to spend summers on the shores of Lake Ossipee in Freedom, NH. Ruth recently gifted a box of UNH memorabilia to the university archives. UNH Magazine received word that Charles K. Besaw passed away on April 27, 2019, at age 101. He served in the Army in World War II and was discharged a First Lieutenant, AGD, in the Reserves. Before retiring in 1985, Charles was the owner of the Woolson and Clough Insurance Agency in Lisbon, NH. He was an incorporator of the former Savers Bank (Littleton), and a former trustee of both the Littleton Hospital and the North Country Community Health Services. Charles was predeceased by his wife, Rita, and is survived by his two children, two granddaughters and two great granddaughters.

Since mid-March, more than 2,000 alumni and friends have tuned in to a new series of webinars, hosted by UNH alumni relations and covering everything from anti-racism and the pandemic to cooking and mindfulness.

“We’re all in this together, and the webinar topics reflect that. We’re offering helpful insights from UNH experts for people trying to deal with a variety of challenges in our collective ‘new normal,’” says Jenn Woodside, director of university engagement. “Our goal is to provide resources to our alumni and the general public by inviting them to experience the know-how that UNH has to offer.”

Offered roughly eight times a month throughout the late spring and summer, the most popular webinars have addressed how coronavirus is affecting the stock market, diversity and inclusion efforts at UNH through the lens of the Black Lives Matter movement, and tips for parents trying to teach their children through virtual classrooms.

So while it’s true that COVID-19 has meant a delay in the usual on-campus alumni events for much of 2020, these online events have made it possible for alumni around the globe to connect with their alma mater, without ever leaving their homes.

Webinars continue in December with a presentation featuring journalism professor Tom Haines and renowned Boston journalist Natalie Jacobson ’65 discussing “the age of disinformation.” See the full schedule at unh.edu/alumni, under the events section. You can also watch a recording of any past webinar here.

amela Chatterton-Purdy ’63 remembers clearly the first time she witnessed blatant racism. It was 1955. She was 15, living in Connecticut. Her father worked for Allied Van Lines. One day, he came home excited to share that he had received a call from Jackie Robinson, who, as first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers, had become the first Black major league baseball player. Number 42 wanted Allied Van Lines to move him to Stamford.

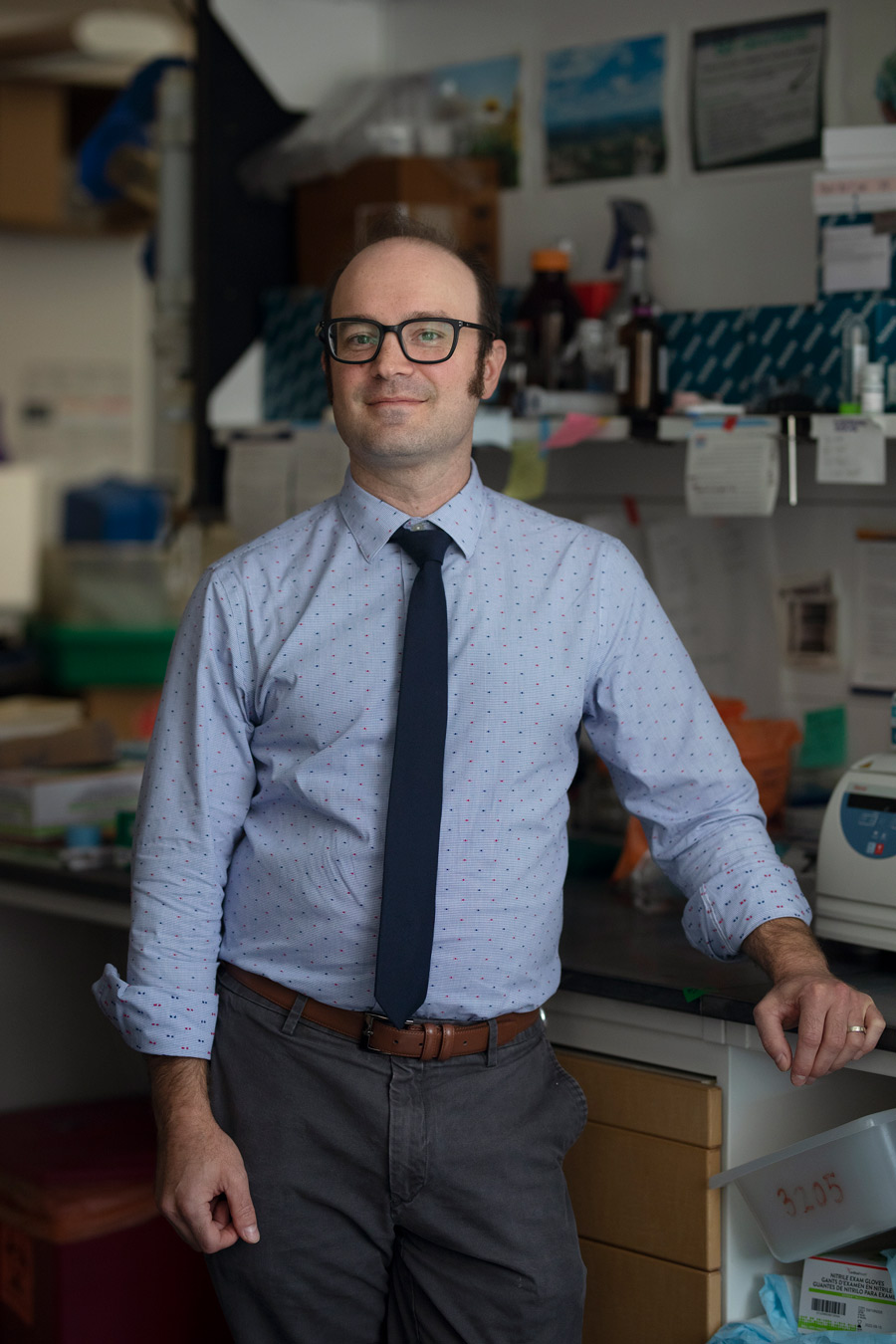

on’t let the Clark Kent glasses fool you: When Timothy Sheahan ’99 goes into saving-the-world mode, he doesn’t duck into a phone booth and emerge in a cape and tights. Instead, he dons a full Tyvek suit, two pairs of gloves, booties and an enclosed hood connected to a battery-powered respirator that delivers sterile breathing air — and locks himself into a room with a biosafety cabinet. That’s because, since the beginning of the year, Sheahan has been directly engaging with something that virtually the entire world has turned itself upside down to avoid: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. A virologist in the Baric Lab at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, Sheahan is an expert on coronaviruses, and one of a handful of research scientists on the frontlines of the efforts to find a treatment that might halt the global pandemic.

“There’s definitely a lot of pressure,” Sheahan says of his work evaluating new drugs and potential vaccines for COVID-19. “We’re working at warp speed and the stakes are incredibly high. Being involved in this effort has been the best thing ever and the worst thing ever at the same time.”

yan Dion ’04 may not have envisioned a career in the restaurant industry, but that’s precisely where he’s making his mark.

The co-founder and chief operating officer of 110 Grill, Dion steers one of the nation’s fastest-growing restaurant chains, a six-year-old enterprise with 31 restaurants peppered across three New England states. The Massachusetts Restaurant Association’s reigning Restaurateur of the Year, the 39-year-old Dion sat with UNH Magazine to discuss his unlikely journey into the restaurant world and 110 Grill’s rapid ascent.

As a UNH undergraduate, Dion worked part-time at the TGI Fridays in nearby Newington. Though intrigued by the industry — he even built a business plan for an Italian restaurant as a senior class project — Dion didn’t seriously consider a restaurant career. “I was happy to have work and spending money. Being a restaurant entrepreneur never hit my radar.”

early 10 years after graduating from UNH with a degree in classics, Jessica Ouellette ’11 still thinks about Capt. Benjamin Keating ’04. She even remembers the day more than a decade ago on which she was awarded a scholarship in his name by the UNH humanities department.

“Professor Stephen Trzaskoma was presenting the award, and I remember he got extremely choked up when he started talking about Ben,” she says. “I remember feeling so honored; Ben clearly had such an impact on the faculty, and his family clearly feels a strong connection to UNH.”